ONE OF US, I won’t specify which, determined that the bus to the airport left at 11:45, so we got to the bus stop at about 11:30. Two busses soon arrived, one with a few passengers, the other empty. Both drivers strolled away for a few minutes, for a smoke I suppose or a humanitarian mission to a facility inside the Sonoma County Airport, where we were catching our bus to SFO. When they re-emerged they informed us that they had no intention, neither of them, to go on to San Francisco.

So we drove, and Eric came with us, as he’d planned to take our car back home, and we pulled into SFO right behind the bus we should have taken — at 11:15, not 11:45. Then, on going through security, one of us, I won’t specify who, had to unpack one of our backpacks completely, because the x-ray machine insisted there was a pair of folding scissors in it, though we both knew we’d never owned a pair of folding scissors. But there ultimately they were, in a first-aid kit meant to cope with blisters, an issue never far from our minds as we embark on another walking trip.

Oh well. My report on the flight is nothing but favorable. The Dutch national airline KLM has kept its old-fashioned, comfy attitude toward service. The bar is open and free; the meals were tolerable; the in-flight entertainment can’t be beat — each seat has its own DVD player, with dozens of movies, documentaries, and features available — as well as scores of music recordings. I watched a British documentary on 5th- to 10th-century Islamic innovative mechanics, optics, and chemistry; and then I listened to the Mozart clarinet concerto, two Schumann string quartets, some bossa nova, and cuts by Teddy Wilson, Billie Holiday, and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The plane left on time and arrived fifteen minutes early. There wasn’t much leg room, of course, but one expects that. Six or eight passengers in our crowded coach section were coddled a little bit extra: they turned out to be a sailing team returning in triumph, as they’d just taken a prize in San Francisco. The pilot congratulated them on the public address system, and we all applauded them.

The baggage took almost no time to arrive. (Of course we checked only one piece, since much of the trip this time will be on foot, and we’ll be carrying everything for that period on our backs.) We enjoyed re-acquainting ourselves with the big modern airport at Schiphol, whose crowds of travellers seem particularly cosmopolitan — though there are many Dutch, Dutch of all sizes and colors, businessmen with cigars in their pockets, nuns in their crisp grey suits, tattooed mothers tethered by green plastic leashes to two or three little kids pulling in various directions, pretty girls whose skin is peaches and cream, or cafe au lait, or nearly ebony, all chattering away in Dutch, whether to present friends or, as is increasingly the case, absent ones momentarily in touch thanks to Nokia and Motorola and Vodafone.

We’re in a cheap hotel, the Seasons, on the Stadhouderskade, not far from the broad Amstel river, the river whose dam lies at the heart of the old city. There are cheap hotels there, too, near the Dam: we didn’t take one, because I assumed they’d be noisy. And of course it turns out the Stadhouderskade is an arterial favored by braying emergency vehicles: it’s going to be a noisy night.

But the beds, though narrow, are soft and clean; the bathroom is acceptable though lacking a tub; and there is wi-fi — though it isn’t free, and I’ve yet to figure out how to send group e-mails on it. Perhaps that’s insoluble: if so, this blog will be the only way for me to entertain myself with my Dispatches, at least for the time being. We’ll see how it goes.

Wednesday, August 31, 2005

Wednesday, August 24, 2005

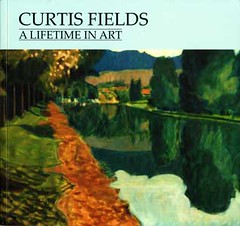

Curtis Fields

A MAN I HARDLY KNOW sends a copy of his new book, Curtis Fields: a Lifetime in Art [ISBN 0-9766520-0-5]. I met Curtis at the birthday party of a mutual friend, as Dickens says, some years ago. He was a handsome, quiet, tall man; in his seventies, I thought. Conversation was guarded at this party, which took place in a small Napa Valley winery. Lindsey and I were, it seemed to us, among the few people present who had not voted for the current occupant of the White House, and neither politics nor even many cultural issues seemed suitable ground for table talk at what was after all meant to be a festive occasion.

As the party was breaking up Curtis mentioned that he was a painter,and that he had a show up at the moment, in a small art gallery in Tiburon, and would I like to stop by and see it and let him know what I thought.

Since we were driving down to San Francisco a few days later we stopped off. We liked much of what we saw. His paintings don’t break new ground. They’re easel paintings, never more than four feet in either direction, very colorful, quite representational, with enough internal life and motion to be interesting even though they shun any attempt at intellectual content.

I’ve always been a sucker for this kind of thing — a weakness that certainly hampered my credibility as an art critic, back in the days when such a thing mattered, if it did. Gradually I’ve come to understand the reason for this weakness: my growing up in the country, away from intellectual conversation, from trips to museums, but constantly within the beauty and the vitality of nature.

I dropped Curtis a postcard to tell him I liked much of what I’d seen, and a while after that he wrote asking if I’d mind writing a paragraph or two about his paintings, explaining that he’d use them in a book he was assembling .

I explained that this wasn’t the kind of thing I did, but he countered that I’d recently written a catalogue essay for a gallery (a retrospective of paintings by Jack Jefferson), and all he wanted was just a few sentences. So I obliged.

He asked what I’d charge, and I said forget it, and he insisted, and I said Oh just send me a little drawing, a very little drawing. And he did, a charming ink sketch of a farmhouse among pines and blossoming fruit trees somewhere in Tuscany.

And now the book has arrived. I like leafing through it. I like seeing the unpretentious depictions of places he’s enjoyed: Tuscany, Mexico, California, Provence. Who doesn’t enjoy such places?

I like the still lifes and especially the interiors, which remind me that the interiors of familiar rooms, bedrooms and living rooms and especially dining areas, have a life of their own, even when they’re not occupied, when they’re “empty,” partly because of the meaningfulness of the ratios of their heights and widths and volumes, of their colors, of their light and shadow, and partly because of their memories of the life we’ve left within their walls the many times we’ve occupied them.

As the party was breaking up Curtis mentioned that he was a painter,and that he had a show up at the moment, in a small art gallery in Tiburon, and would I like to stop by and see it and let him know what I thought.

Since we were driving down to San Francisco a few days later we stopped off. We liked much of what we saw. His paintings don’t break new ground. They’re easel paintings, never more than four feet in either direction, very colorful, quite representational, with enough internal life and motion to be interesting even though they shun any attempt at intellectual content.

I’ve always been a sucker for this kind of thing — a weakness that certainly hampered my credibility as an art critic, back in the days when such a thing mattered, if it did. Gradually I’ve come to understand the reason for this weakness: my growing up in the country, away from intellectual conversation, from trips to museums, but constantly within the beauty and the vitality of nature.

I dropped Curtis a postcard to tell him I liked much of what I’d seen, and a while after that he wrote asking if I’d mind writing a paragraph or two about his paintings, explaining that he’d use them in a book he was assembling .

I explained that this wasn’t the kind of thing I did, but he countered that I’d recently written a catalogue essay for a gallery (a retrospective of paintings by Jack Jefferson), and all he wanted was just a few sentences. So I obliged.

He asked what I’d charge, and I said forget it, and he insisted, and I said Oh just send me a little drawing, a very little drawing. And he did, a charming ink sketch of a farmhouse among pines and blossoming fruit trees somewhere in Tuscany.

And now the book has arrived. I like leafing through it. I like seeing the unpretentious depictions of places he’s enjoyed: Tuscany, Mexico, California, Provence. Who doesn’t enjoy such places?

I like the still lifes and especially the interiors, which remind me that the interiors of familiar rooms, bedrooms and living rooms and especially dining areas, have a life of their own, even when they’re not occupied, when they’re “empty,” partly because of the meaningfulness of the ratios of their heights and widths and volumes, of their colors, of their light and shadow, and partly because of their memories of the life we’ve left within their walls the many times we’ve occupied them.

Sunday, August 21, 2005

St. Helena Sunset

I’d wanted to reach this peak since my tenth year, when I began watching the curious, elegant, sensuous profile of Mt. St. Helena from various sites in Sonoma County. Finally it was time to do it, with two friends — an old one, my brother Jim; a newer one, Mac Marshall. It took three hours to get there from the parking lot, almost that long to get back. Fabulous sunset; equally fabulous rise of the full moon.

They say you get a thousand moons. This was number 910 for me. I enjoy them all.

They say you get a thousand moons. This was number 910 for me. I enjoy them all.

Friday, August 19, 2005

Sorry about that...

YES, I KNOW, the whole point of a blog is that it be frequent, preferably daily.

I plead age: ik ben jarig, as the Dutch say, I'm yearish -- it's my birthday. Seventy years old.

We threw a little party to celebrate, and it took a while to get ready. That's part of the excuse. The other part is, well, there are so many things to write about!

The daily news brings one unbelievable absurdity after another. I've thought about blogging on:

� Why Globalism Must End

� Hearing Mozart

� Language, Numbers, and evading reality

� Real Authenticity

� Gangs and Fundamentalism respond to postmodern Globalism

...and I may yet get there.

But first I have a small local mountain to climb. If I make it, and get back, I'll let you know about it in a couple of days... here.

I plead age: ik ben jarig, as the Dutch say, I'm yearish -- it's my birthday. Seventy years old.

We threw a little party to celebrate, and it took a while to get ready. That's part of the excuse. The other part is, well, there are so many things to write about!

The daily news brings one unbelievable absurdity after another. I've thought about blogging on:

� Why Globalism Must End

� Hearing Mozart

� Language, Numbers, and evading reality

� Real Authenticity

� Gangs and Fundamentalism respond to postmodern Globalism

...and I may yet get there.

But first I have a small local mountain to climb. If I make it, and get back, I'll let you know about it in a couple of days... here.

Monday, August 01, 2005

Comment c’est ici a cette heure...

A DEAR OLD FRIEND spent the afternoon yesterday. He’s French, a Parisian, and intelligent, somewhat reflective man though a very active one, formerly in law, now in film production.

We’d seen the film he brought the previous night, as part of the Napa Film Festival; I’ll write about it later. (It’s not yet in release in this country, so there’s no hurry — but it should be in distribution; it’s really quite wonderful.)

We had lunch — sliced tomatoes and basil, a green salad, good cheese, all from Healdsburg. And a bit of cheap Pinot Grigio from Trader Joe. Truly we do live well hereabouts!

We talked about our children, marriage, sex, politics, terrorism, the war. It was the kind of conversation you have with an old friend you haven’t seen in years. And it reminded me once again of the gulf between the American and the French mentality. And it revealed, when I heard myself telling him what has become of the United States since last he visited, perhaps nine years ago, how drastic the change has been.

To simplify things as much as possible, the current American mentality is both quantitative and linear; the French sensibility is qualitative and situational. I think one of the most fascinating aspects of current American politics, left and right, is the insistence on absolute values. Politics is, famously, the art of the possible: and the possible is never absolute. (This is what Susan Sontag meant when she wrote that “meaning is never monagamous”.)

Philippe and his brother are the first men in his lineage to survive into their fifties in a number of generations. World War II; World War I; the Franco-Prussian War; various revolutions; the Napoleonic Wars... the litany of sorrow goes back for generations. France and Germany agree now, and so I think does most of the rest of the European Union, that peace in Europe is worth paying for — paying money and sacrificing, where necessary, long-held ideas (“values” if you like) of narrow national interest.

I said, well, every war in Europe ended with negotiation; and one of the earmarks of the current international crisis is that the United States is irrationally indisposed to negotiate. We explained what was happening with the Bolton nomination — that it would be a recess appointment, unconfirmed by the Senate — and we asked what he thought, what people in Paris thought, of our Secretary of State; and his eyes widened and he was at a loss for English words, though “worse than Thatcher” and “dragon” came to mind.

Over and again, whether the subject was politics or sex, culture or environnment, I was struck with what I take to be a representative French intelligence taking an attitude of practicality, of negotiation, of compromise, of workability, opposed to what seems to me to be the prevailing American attitudes of principle, of dictation, of win-or-lose, of entrenched impracticality.

Most of all he was saddened and almost unbelieving when we described what seems the present state of our country: the impotence of the left in the face of the (probably jiggered) elections of 2000 and 2004, the poverty, the intellectual poverty of the middle class, the decline of the educational system, the collapse of health care, the default of pension systems. These are all areas in which the United States seemed to offer noble and practical models at one time, to a Europe left destitute and destroyed by its series of wars: how had it all collapsed to this extent in so short a time?

He turned for understanding to Germany, 1936: a democratically elected leader of great charisma, dedicated to a clearly stated ideal of national policy, patient enough for its implementation so gradually that the horrors of its working details could be either unnoticed or accepted by even the intelligent and educated classes, let alone the ignorant, fearful, and readily inflamed sectors.

He saw Stalinist parallels as well, in the manipulation of the industrial and banking cartels through their attachment to an increasingly militaristic society, and in the co-option of established press and educational institiutions.

It was fine to renew an old friendship, to have a pleasant lunch, then to go in to Healdsburg for supper at El Sombrero and walk the twilit streets, oddly bare on a cooling Sunday evening. But we look forward to spending next month in Holland again, beset though it is by Christian-Muslim disagreements, vulnerable though it may be to London- and Madrid-style terrorism, allied though it is to Bush’s — our — invasion and occupation of Iraq.

I have the feeling Europe is adjusting herself to all this, and will somehow come through. I count on her long tradition of addressing these things, of trying one way or another of accommodating them and getting on with a daily life in which a modicum of security from age, illness, and hunger is accounted a normal guarantee, a part of a social contract that is worth keeping, on every side of the agreement.

We’d seen the film he brought the previous night, as part of the Napa Film Festival; I’ll write about it later. (It’s not yet in release in this country, so there’s no hurry — but it should be in distribution; it’s really quite wonderful.)

We had lunch — sliced tomatoes and basil, a green salad, good cheese, all from Healdsburg. And a bit of cheap Pinot Grigio from Trader Joe. Truly we do live well hereabouts!

We talked about our children, marriage, sex, politics, terrorism, the war. It was the kind of conversation you have with an old friend you haven’t seen in years. And it reminded me once again of the gulf between the American and the French mentality. And it revealed, when I heard myself telling him what has become of the United States since last he visited, perhaps nine years ago, how drastic the change has been.

To simplify things as much as possible, the current American mentality is both quantitative and linear; the French sensibility is qualitative and situational. I think one of the most fascinating aspects of current American politics, left and right, is the insistence on absolute values. Politics is, famously, the art of the possible: and the possible is never absolute. (This is what Susan Sontag meant when she wrote that “meaning is never monagamous”.)

Philippe and his brother are the first men in his lineage to survive into their fifties in a number of generations. World War II; World War I; the Franco-Prussian War; various revolutions; the Napoleonic Wars... the litany of sorrow goes back for generations. France and Germany agree now, and so I think does most of the rest of the European Union, that peace in Europe is worth paying for — paying money and sacrificing, where necessary, long-held ideas (“values” if you like) of narrow national interest.

I said, well, every war in Europe ended with negotiation; and one of the earmarks of the current international crisis is that the United States is irrationally indisposed to negotiate. We explained what was happening with the Bolton nomination — that it would be a recess appointment, unconfirmed by the Senate — and we asked what he thought, what people in Paris thought, of our Secretary of State; and his eyes widened and he was at a loss for English words, though “worse than Thatcher” and “dragon” came to mind.

Over and again, whether the subject was politics or sex, culture or environnment, I was struck with what I take to be a representative French intelligence taking an attitude of practicality, of negotiation, of compromise, of workability, opposed to what seems to me to be the prevailing American attitudes of principle, of dictation, of win-or-lose, of entrenched impracticality.

Most of all he was saddened and almost unbelieving when we described what seems the present state of our country: the impotence of the left in the face of the (probably jiggered) elections of 2000 and 2004, the poverty, the intellectual poverty of the middle class, the decline of the educational system, the collapse of health care, the default of pension systems. These are all areas in which the United States seemed to offer noble and practical models at one time, to a Europe left destitute and destroyed by its series of wars: how had it all collapsed to this extent in so short a time?

He turned for understanding to Germany, 1936: a democratically elected leader of great charisma, dedicated to a clearly stated ideal of national policy, patient enough for its implementation so gradually that the horrors of its working details could be either unnoticed or accepted by even the intelligent and educated classes, let alone the ignorant, fearful, and readily inflamed sectors.

He saw Stalinist parallels as well, in the manipulation of the industrial and banking cartels through their attachment to an increasingly militaristic society, and in the co-option of established press and educational institiutions.

It was fine to renew an old friendship, to have a pleasant lunch, then to go in to Healdsburg for supper at El Sombrero and walk the twilit streets, oddly bare on a cooling Sunday evening. But we look forward to spending next month in Holland again, beset though it is by Christian-Muslim disagreements, vulnerable though it may be to London- and Madrid-style terrorism, allied though it is to Bush’s — our — invasion and occupation of Iraq.

I have the feeling Europe is adjusting herself to all this, and will somehow come through. I count on her long tradition of addressing these things, of trying one way or another of accommodating them and getting on with a daily life in which a modicum of security from age, illness, and hunger is accounted a normal guarantee, a part of a social contract that is worth keeping, on every side of the agreement.

Sunday, July 24, 2005

Well, of course it’s not that simple...

THE DISCUSSION CONTINUES re. food costs, quality, and quantity.

The issues raised Friday by Julie Powell (see below for web citation) were two: that organic food costs more than many can or want to pay; and that cuisine, both haute and peasant, evolved to make the best of available materials, even when less than ideal.

Let’s concentrate on the first issue, often floated these days in the press. Here too there are two things to consider: the relative cost, to both consumer and society as a whole, of the raw materials of food; and the relative amount we pay these days for our food.

It’s not news that a significantly greater amount of food consumed by today’s typical city-dweller is eaten in restaurants or as “take-out”: this enormously increases the cost of the food consumed. Unfortunately for the clarity of our discussion, much of this cost is hidden, subsidized, or simply ignored -- the direct costs of manufacturing, wrapping, shipping, and preparation; the indirect costs of advertising and marketing; the resultant costs (to society, primarily) relating to medical problems, many of these no doubt yet to be discovered — though the increase in obesity is clearly among them.

The same observations apply to the great increase in the consumption, at home, of food prepared from packaged mixes and the like. Beginning with the end of World War II these “convenience” items have quite changed the daily approach of most citizens of developed societies toward just what constitutes cooking and dining. It has finally resulted, of course, in the rise of a considerable backlash, and the return of cuisine — whether “traditional” or haute — to the household kitchen. But this backlash has yet to reach the mainstream, though its adherents have gained considerable attention — enough, in fact, to precipitate backlashes of their own: witness Powell’s piece in Friday’s New York Times.

Discussion of comparative costs of provender raised sustainably and not, and of conventional and pre-packaged food, generally ignores a larger question more directly important, I think. I have in mind the considerable shift of values represented by the rise of convenience as a factor of daily life. Food used to represent roughly a third of our household budget, shelter another third, everything else bundled into the remainder. This was the case in my parents’s household, and in my own in the 1950s.

In those days a good percentage of households employed one partner at home, preparing food, maintaining shelter and clothing, and supervising the education and well-being of the next generation. The other partner was employed outside the home, winning the money needed to maintain the entire system.

An interesting change in the social system developed in the generations before World War I, when the middle classes gained considerably in numbers. The labor of maintaining the wealthy or upper-class household involved a servant class. This was out of the question for the middle classes, for a number of reasons, and an entire industry evolved to solve the problem. You can follow it in advertisements in old issues of household magazines, not to mention ancient mail-order catalogues: electric lights, toasters, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, mangles all promised to replace expensive and intrusive and, finally, unavailable servants -- and in fact to rescue the middle-class housewife from being a servant herself, her own servant.

After World War II another significant step was taken in this evolution, when Industry promised the housewife she need never again be slave to her kitchen. Frozen food, cake mixes, and ultimately TV dinners were her liberation. At the same time, of course, women in increasing numbers went to work, and in our society the dual-income family has become the norm, necessary because of the increased cost of maintaining this kind of a life.

The costs, both direct and indirect, of this inherently inefficient and (to my way of thinking) over-industrialized urban lifestyle have changed our very perception of something as apparently simple as the cost of food. It's all very well to return to the argument that this discussion is irrelevant to the poor bloke faced with the cost of his radish or his artichoke: clearly the cause and correction of the social shift in food economy is beyond him.

But I think we must consider the injustice of continuing to promise cheap and wholesome life in an increasingly expensive and unwholesome economy, remembering the root meaning of the word “economy”: household management.

All of these problems, in my view, and a good many others (transportation, for instance, and education, and land use...) are interrelated, and have to do with the human animal’s proclivity toward irresponsibility, toward putting cost and labor off on someone else, inferior in social position, or not yet even born, or preferably both. In our present big democratic classless societies the average guy with his supermarket pushcart can’t or won’t think about these things.

It’s that much more important that others of us do, and that we continue this discussion.

Saturday, July 23, 2005

The ethics of organic food

A FEW FRIENDS ASK what I think of an op-ed by Julie Powell in yesterday’s New York Times, “Don't Get Fresh With Me!”.

Not much, really. She makes two points in her column, both of them simplistic; straw men set up as subjects for a newspaper entertainment. One has to do with the economies involved: here her memorable line is “When you wed money to decency, you come perilously close to equating penury with immorality”.

But the organic (or, I would prefer, sustainable) food movement does not wed money to decency. It’s a specious argument that organically or sustainably produced food is more expensive than the product of what has presumptiously come to be called “conventional” agriculture, for at least two reasons.

First, much of the cost of modern chemical- and petroleum-dependent agriculture is simply ignored and deferred — not paid at all (yet), or posted to accounts conveniently kept elsewhere. Second, much of what is invented, produced, sold, and eaten as “food” in today’s society is and has been developed as deliberately expensive alternatives to real food. When by far the majority of the potato crop is bred (or gene-manipulated), raised, harvested, and tooled expressly for potato chips and french-fries, it’s essentially meaningless to compare the cost of organic potatoes in the farmer’s market with giant russets or boilers in the supermarket.

Her other point is more interesting, though less arresting: that cooking is not (and is more than) shopping. But this too is set up with specious reasoning and outlandish generalization:

“For the newer generation, a love for traditional fine cuisine is cast as fussy and snobbish, while spending lots of money is, curiously, considered egalitarian and wise”.

“I object to this equation,” she goes on, and well she might, and so do I — both because it is false, and because it is a rhetorical distraction in her column. Good cuisine will always be a matter of finding the best provender you can and doing the most appropriate thing with it, depending on the cultural context you’re operating in.

It’s an art, like any other: it represents the intersection of material, method, and mores. All else is simply entertainment, and often entertainment whose expense, finally, can no longer be justified.

Not much, really. She makes two points in her column, both of them simplistic; straw men set up as subjects for a newspaper entertainment. One has to do with the economies involved: here her memorable line is “When you wed money to decency, you come perilously close to equating penury with immorality”.

But the organic (or, I would prefer, sustainable) food movement does not wed money to decency. It’s a specious argument that organically or sustainably produced food is more expensive than the product of what has presumptiously come to be called “conventional” agriculture, for at least two reasons.

First, much of the cost of modern chemical- and petroleum-dependent agriculture is simply ignored and deferred — not paid at all (yet), or posted to accounts conveniently kept elsewhere. Second, much of what is invented, produced, sold, and eaten as “food” in today’s society is and has been developed as deliberately expensive alternatives to real food. When by far the majority of the potato crop is bred (or gene-manipulated), raised, harvested, and tooled expressly for potato chips and french-fries, it’s essentially meaningless to compare the cost of organic potatoes in the farmer’s market with giant russets or boilers in the supermarket.

Her other point is more interesting, though less arresting: that cooking is not (and is more than) shopping. But this too is set up with specious reasoning and outlandish generalization:

“For the newer generation, a love for traditional fine cuisine is cast as fussy and snobbish, while spending lots of money is, curiously, considered egalitarian and wise”.

“I object to this equation,” she goes on, and well she might, and so do I — both because it is false, and because it is a rhetorical distraction in her column. Good cuisine will always be a matter of finding the best provender you can and doing the most appropriate thing with it, depending on the cultural context you’re operating in.

It’s an art, like any other: it represents the intersection of material, method, and mores. All else is simply entertainment, and often entertainment whose expense, finally, can no longer be justified.

Two more plays

Ashland, Oregon

TWO MORE PLAYS to report on here from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. We saw Love’s Labour’s Lost night before last, in the outdoor Elizabethan Theater, not an ideal theater I’ve decided for the performance of Shakespearean comedy, with last year’s As You Like It and the previous year’s Midsummer Night’s Dream in mind: it’s too hard for these aging ears to follow Shakespeare’s delicious lines tumbling about this huge, imposing stagehouse; especially when seated at almost the exact center of the audience, with maximal reverberation from every angle.

Love’s Labour’s Lost was by no means all lost, though. For one thing, it was a visual delight, as every play here this season has been (so far: we have two yet to see, and a third will not open until after we leave). Kenneth Albers, a magnificent Malvolio a couple of nights earlier in Twelfth Night, directed this play, setting it in an unspecified 1920s location while keeping all the original references to Navarre and Brabant and all that; Marjorie Kellogg provided stylish stage furnishings; and Susan Mickey invented costumes so delightful and astonishing they almost upstaged the cast.

Added to this eye feast was the slightly larger than life posturing, prancing, and positioning. Ferdinand and his three lords Berowne, Longaville, and Dumaine (Brent Harris, Jeff Cummings, Jose Luis Sanchez, and Christopher DuVal) were beautifully counterpoised by the French princess and her ladies (Catherine Lynn Davis, Tyler Layton, André Ferraz, Sarah Rutan): when Berowne asks Rosaline Did I not dance with you in Brabant once? he precipitates a verbal gavotte of a banter that typifies the entire play.

The production does perhaps go over the top with John Pribyl’s portrayal of the absurd Spaniard Don Adriano de Armado, assisted by the squeaking spritely Julie Oda as Moth; and by their counterpoise, the pedant Holofernes (played here by the hilarious Eileen DeSandre) and the curate Sir Nathaniel (James Edmondson). Armado is all but impossible to understand, but then he’s a Spaniard; Holorernes ditto, but then (s)he’s talking bad pedantic Latin much of the time.

Once again, Shakespeare represents we uncomprehending audients with clowns and dullards on the stage, Costard, Dull, and Jaquenetta (Ray Porter, Jeffrey King, Jaclyn Williams), and they represent us perfectly, following the action occasionally, understanding it infrequently, enjoying it always.

Then there’s the fascinating role of Boyet, the usher to the Princess — a role recalling Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte. Boyet’s a practical skeptic and a nearly neutral onlooker, the Audience as comprehending if you like, and Derrick Lee Weeden, who is always suave, intelligent, and stylish, was the perfect man for the role.

It’s a wonderful play, beautifully conceived, masterfully directed and produced, and often brilliantly acted, and I’d see it again in a minute. Next time, perhaps, with the infrared listening device.

OSF CONTINUES ITS INVESTIGATION of the important mid-20th century Italian playwright Eduardo De Filippo with his Napoli Milionaria!, a drama with comedy and poignancy set in Naples during World War II. In the first act, in 1942, an extended family gets by on dealings in the black market, in spite of the father's disapproval. After the intermission it is 1944; Naples has been liberated; the father has escaped from a German labor camp to find his wife apparently rich, their squalid apartment made magnificent.

This is a complex play easily approached. A big cast, a detailed set, authentic-looking props, costumes, and gestures propel a vehicle that quickly steers among madness, disease, high comedy, ordinary poignancy, and moral imperatives. Richard Elmore was memorable as the father Gennaro; Linda Alper (a co-translator of the play) as his wife Amalia; the rest of the cast just as solid, idiomatic, pointed, often moving in their keenly balanced roles.

We saw De Filippo’s hilarious Saturday, Sunday, Monday here three years ago (can it be that long?), and Napoli Milionaria! offered an enticing further glimpse of his wit and sympathy, so specific to his beloved Naples but so transferable to our own time and place. We need these plays; I’m grateful to OSF for producing them, and I hope they catch on elsewhere.

Friday, July 22, 2005

Sclerotic

A LITTLE PROBLEM WITH THE EYE puts me in mind of mortality. (Excuse the exaggeration: I’ve been seeing Shakespeare plays.) And then I find, in the to-do pile, this poem, written a few years ago for Carl Rakosi:

SO, Carl, a friend,

another Charles, writes of your impending

birthday — a centennial!

And I’ve dreamed

this morning of Symphony and Book,

thinking there must be something that relates them,

distinguishes them from casual collections,

leverages, as investors use the word,

their Meaning into greater Meaningfulness.

Well, life’s like that.

The life well lived, in interesting times —

no Chinese curse!

Observing, mulling it over,

coming to no conclusions, just collecting.

You do one thing, and then you do another,

The words and lines pile up. Or else they don’t.

With any luck we’ll get it figured out,

or some of it, in time. Or else we won’t.

You say it well:

the larger, perhaps different meaning

these poems have (newly strewn), is to be found,

when it is there,

in the arrangement.

“What will not be found is the coherence

of a composition.”

We aren’t composed.

Like books and symphonies we take our shape

as other eyes and ears encounter us.

Meaning is basic.

I’ve learned from you.

Intention is my biggest enemy,

As you know well!

And with him comes

Remorse,

Intention’s lapdog. Slam the doors on both!

That’s what I think I’ve heard you telling me;

Our Book evolves with us, thinking, feeling,

discarding when it must, or falling silent,

And none of us can tell where it will end.

July 7 2003

Thursday, July 21, 2005

The Hell you say!

Ashland, Oregon

EIGHT OF US STAY in this house for a week, seeing plays. We don’t always see eye to eye, and yesterday was one of those days. We saw two plays: a very new one called Gibraltar in the afternoon, a very old one — well, maybe not all that new — in the evening.

Thing is, many of the objections to the new play could have been lodged against the old one. Narrator kept getting between play and audience. Events seemed contrived. Characters spoke in language not entirely convincing. Playwright seemed concerned with abstractions, not real issues.

And of course it’s not entirely fair to blame Octavio Solis, born in El Paso say forty years ago, for not writing like Christopher Marlowe, born in London say four hundred years earlier. Languages, cultures, milieux, the states of their art — all are immeasurably different. Yet the similarities of their plays invite, nearly demand the comparison.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus is of course a cultural icon, precisely because its story centers on a character who stands as a metaphor for a central issue as alive today as it was in the first Elizabeth’s reign — the arrogance of the individual intelligence demanding to pursue knowledge however far it takes him from the ethical, even moral issue of human existence as it grows organically out of its natural context.

The issue is perhaps more meaningful, more dire today than even in Marlowe’s day, when Europe was poised to “discover,” subdue, and exploit a full half of Earth, made available only a lifetime earlier through unimaginable developments in human knowledge and technology.

Marlowe’s genius lay in his lucky opportunity to bring the new flourish of the modern English language — and the metropolitan conventions and resources of London’s theater — to this utterly new situation, at the same time close enough to the religious wars of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation — and the final flowering of medieval alchemy — to weave elements of those immense issues into his narrative.

Solis’s problem lies in the near-impossibility of bring the very similar ingredients of his own heritage — born in El Paso, witness to the culture clashes of Latino and mainstream white American “values,” not to mention the essential triviality of social-status and -class signifiers — to life in a play contrived, essentially, I think, in order to develop a concept: namely, that a significant evening of theater — one with relevance to similarly big cultural issues in a society undergoing similarly critical change and collisions — can be generated out of an ongoing interaction between playwright and actors, with the facilitation of what is arguably the most important repertory theater company in the country.

WE SAW GIBRALTAR in the small “New Theater,” which seats only a couple of hundred people in a very flexible house set, this time, in a very deep three-sided thrust configuration. The set was striking: a loft apartment in San Francisco, with only a double mattress and a couple of chairs to furnish it; at the back a huge window looking across the dark night San Francisco Bay toward the lights of the East Bay hills. On the floor, curving lines making a grid connecting with the mullions of that huge window, which opened like a garage door from time to time to facilitate the intrusion of the next scene.

For Gibraltar is an episodic play, held together by a framing story for two actors: a Latino man following his runaway bride up the sandy coast from Mexico; a Chicana woman mourns the apparently meaningless suicide of her husband. The central issue is rebellion against these meaningless deaths and departures: what might we have done to prevent them.

The narrative is fleshed out by three skits, I would call them, or one-act narratives, a drama prof might say: an aging sculptor and her handsome model (the son of a man she’d not had nerve to commit to years before); a normal-guy cop and his wife-turned-Lesbian; a wildlife journalist caring for a wife with Alzheimer’s irresistibly tempted by the artist he hires to help her through art therapy.

The result is a disappointment, another exercise in What-If. The play could conceivably be saved, be developed into an integrated, fully achieved study in parallel lives, something like that recent movie/book that brought Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway into early-21st-century American life, for those unable to accept and enjoy it on its own terms.

But it is terminally frustrated by two flaws. First, instead of showing us a theatrical series of events, it continually gives us someone telling us about them, then only apparently grudgingly illustrating the story with two-dimensional characters.

Second, and more fatally perhaps, the language is banal, overblown, and off-kilter. No one talks as anyone would. A friend said the whole thing sounded translated from the Romanian.

Worst of all, another friend said it was a play that hadn’t needed to be written.

BUT THEN, YESTERDAY EVENING, we took our seats in the Elizabethan Theater for The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. I admit that given the heat, the lack of sleep, the quantity of food and drink, I dozed off from time to time in the first act — in spite of the brilliant acting, the costumes, the poetry. In Act II, though, there was little chance for sleep. Try as I might I was distracted by the gathering weight of Marlowe’s theater, of James Edmondson’s directing, of Richard Hay’s scenic design, of Robert Peterson’s lighting, of Marie Chiment’s costumes — most of all, of the amazing power, pace, subtlety, and persuasion of Jonathan Haugen’s acting in the title role.

Some friends complained of repetitiousness. I don’t buy that. Marlowe’s pace is not that of the American 21st century, any more than is Bruckner’s. The nearest contemporary American equivalents I can think of, off the top of my head, to Marlowe’s theatrical genius, are Robert Wilson and, before him, Gertrude Stein. There was a moment toward the end of the play when all Hell was breaking loose on stage — quite literally — and Ray Porter, as Mephistophilis, was sitting motionless downstage right, in profile, the left side of his face picked out by a subtle spotlight. You could see one play beyond him, another epitomized by, centered on, that amazing meaningless fascinating inexpressive face.

All my own ego was drawn out of my body; I was beyond sympathy and terror. Marlowe was simply saying WHAT IT IS. When mankind reaches too far beyond his own position within the natural order of things, when he goes beyond what he knows organically and intuitively as you might say, when he dares to reach for things he can only know through artificial technology and the paranatural knowledge those tools reveal to him, he's in deep trouble. Marlowe wrote this, and the entire Oregon Shakespeare Festival had understood it, and relayed it on to us.

I wouldn’t mind seeing this a second time.

EIGHT OF US STAY in this house for a week, seeing plays. We don’t always see eye to eye, and yesterday was one of those days. We saw two plays: a very new one called Gibraltar in the afternoon, a very old one — well, maybe not all that new — in the evening.

Thing is, many of the objections to the new play could have been lodged against the old one. Narrator kept getting between play and audience. Events seemed contrived. Characters spoke in language not entirely convincing. Playwright seemed concerned with abstractions, not real issues.

And of course it’s not entirely fair to blame Octavio Solis, born in El Paso say forty years ago, for not writing like Christopher Marlowe, born in London say four hundred years earlier. Languages, cultures, milieux, the states of their art — all are immeasurably different. Yet the similarities of their plays invite, nearly demand the comparison.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus is of course a cultural icon, precisely because its story centers on a character who stands as a metaphor for a central issue as alive today as it was in the first Elizabeth’s reign — the arrogance of the individual intelligence demanding to pursue knowledge however far it takes him from the ethical, even moral issue of human existence as it grows organically out of its natural context.

The issue is perhaps more meaningful, more dire today than even in Marlowe’s day, when Europe was poised to “discover,” subdue, and exploit a full half of Earth, made available only a lifetime earlier through unimaginable developments in human knowledge and technology.

Marlowe’s genius lay in his lucky opportunity to bring the new flourish of the modern English language — and the metropolitan conventions and resources of London’s theater — to this utterly new situation, at the same time close enough to the religious wars of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation — and the final flowering of medieval alchemy — to weave elements of those immense issues into his narrative.

Solis’s problem lies in the near-impossibility of bring the very similar ingredients of his own heritage — born in El Paso, witness to the culture clashes of Latino and mainstream white American “values,” not to mention the essential triviality of social-status and -class signifiers — to life in a play contrived, essentially, I think, in order to develop a concept: namely, that a significant evening of theater — one with relevance to similarly big cultural issues in a society undergoing similarly critical change and collisions — can be generated out of an ongoing interaction between playwright and actors, with the facilitation of what is arguably the most important repertory theater company in the country.

WE SAW GIBRALTAR in the small “New Theater,” which seats only a couple of hundred people in a very flexible house set, this time, in a very deep three-sided thrust configuration. The set was striking: a loft apartment in San Francisco, with only a double mattress and a couple of chairs to furnish it; at the back a huge window looking across the dark night San Francisco Bay toward the lights of the East Bay hills. On the floor, curving lines making a grid connecting with the mullions of that huge window, which opened like a garage door from time to time to facilitate the intrusion of the next scene.

For Gibraltar is an episodic play, held together by a framing story for two actors: a Latino man following his runaway bride up the sandy coast from Mexico; a Chicana woman mourns the apparently meaningless suicide of her husband. The central issue is rebellion against these meaningless deaths and departures: what might we have done to prevent them.

The narrative is fleshed out by three skits, I would call them, or one-act narratives, a drama prof might say: an aging sculptor and her handsome model (the son of a man she’d not had nerve to commit to years before); a normal-guy cop and his wife-turned-Lesbian; a wildlife journalist caring for a wife with Alzheimer’s irresistibly tempted by the artist he hires to help her through art therapy.

The result is a disappointment, another exercise in What-If. The play could conceivably be saved, be developed into an integrated, fully achieved study in parallel lives, something like that recent movie/book that brought Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway into early-21st-century American life, for those unable to accept and enjoy it on its own terms.

But it is terminally frustrated by two flaws. First, instead of showing us a theatrical series of events, it continually gives us someone telling us about them, then only apparently grudgingly illustrating the story with two-dimensional characters.

Second, and more fatally perhaps, the language is banal, overblown, and off-kilter. No one talks as anyone would. A friend said the whole thing sounded translated from the Romanian.

Worst of all, another friend said it was a play that hadn’t needed to be written.

BUT THEN, YESTERDAY EVENING, we took our seats in the Elizabethan Theater for The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. I admit that given the heat, the lack of sleep, the quantity of food and drink, I dozed off from time to time in the first act — in spite of the brilliant acting, the costumes, the poetry. In Act II, though, there was little chance for sleep. Try as I might I was distracted by the gathering weight of Marlowe’s theater, of James Edmondson’s directing, of Richard Hay’s scenic design, of Robert Peterson’s lighting, of Marie Chiment’s costumes — most of all, of the amazing power, pace, subtlety, and persuasion of Jonathan Haugen’s acting in the title role.

Some friends complained of repetitiousness. I don’t buy that. Marlowe’s pace is not that of the American 21st century, any more than is Bruckner’s. The nearest contemporary American equivalents I can think of, off the top of my head, to Marlowe’s theatrical genius, are Robert Wilson and, before him, Gertrude Stein. There was a moment toward the end of the play when all Hell was breaking loose on stage — quite literally — and Ray Porter, as Mephistophilis, was sitting motionless downstage right, in profile, the left side of his face picked out by a subtle spotlight. You could see one play beyond him, another epitomized by, centered on, that amazing meaningless fascinating inexpressive face.

All my own ego was drawn out of my body; I was beyond sympathy and terror. Marlowe was simply saying WHAT IT IS. When mankind reaches too far beyond his own position within the natural order of things, when he goes beyond what he knows organically and intuitively as you might say, when he dares to reach for things he can only know through artificial technology and the paranatural knowledge those tools reveal to him, he's in deep trouble. Marlowe wrote this, and the entire Oregon Shakespeare Festival had understood it, and relayed it on to us.

I wouldn’t mind seeing this a second time.

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

Amusing deluded glove, rayon

Ashland, Oregon

SO BEGINS — not quite — just about my favorite Shakespeare play, which we saw last night. We saw it a little over a year ago, done by the Los Angeles company A Noise Within in their small deep-thrust theater in Glendale: there it was poetic and romantic, the director’s attention concentrating on Shakespeare’s marvelous text.

Here in Ashland in the much larger Elizabethan Theater, open to the night sky and seating a much larger audience confronting a more conventional stage (though lacking curtain and proscenium), Peter Amster’s direction focussed on another aspect, almost an opposite one, of this rich and complex play: its clowning. Linda Morris was a fine, brash, good-hearted Viola, and Robin Nordli — last year’s Hedda Gabler! — was winning if sometimes ditzy as Olivia. But it is when Shakespeare (and Amster) send in the clowns that this production comes completely to life, reaching out into the big audience whose laughter often drowned out the cast.

Oddly, this was set up at the very beginning, when Michael Elich, as Orsino, speaks that marvelous line: If music be the food of love, play on... The line was overstated, loud, round, and slow, amusing Orsino’s attendants as much as the audience. Orsino is a difficult role to play, I think, central to the play, but not promiinently present; engaging, but not always sympathetic; romantic, but rarely convincingly so. If Mozart and da Ponte had made an opera of this play (oh how I wish they had) his role would have gone to the baritone who sings Don Giovanni. Michael Elich played the role here, and very well indeed (helped immensely, as was everyone, by Shigeru Yaji’s costumes), but in this production he directed your attention not to Olivia but to Sir Toby Belch, somewhat his counterpart at Olivia’s end of town. (For this play, like so many of Shakespeare’s, divides its setting into two camps.)

Robert Sicular was Sir Toby, and he elevated what is often an accessory role into a central one. I think Sir Toby stands often for the playwright himself — commenting on the other characters, the action, even referring, especially in this setting, to other plays in the canon. Dost think because thou art virtuous there’ll be no more cakes and ale? In which case Sir Andrew Aguecheek, wonderfully idiotic in Christopher DuVal’s performance, is perhaps many of us in the audience, standing on uncomprehendingly, blankly repeating bits of text back when spoken to, bumbling in foreign French, giving up, hiding from the constant onslaught of wit and repartee, which goes on whether he comprehends or not. And poor put-upon Malvolio, in Kenneth Albers’ rendition (which recalled his recent Lear from time to time), is of course Shakespeare’s satirical portrait of his rival Ben Jonson.

Altogether it’s a production of Twelfth Night to contemplate, consider, and enjoy. Not by any means the definitive production — but can there ever be an exhaustive interpretation of this play?

IN THE AFTERNOON we had seen quite a different play, August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Perhaps you know the argument: four musicians gather in a 1920s recording studio in Chicago, where they will back a blues singer, Ma Rainey. She’s late, held up by a traffic incident that’s escalated into a minor skirmish in the constantly present race war. Cracker recording engineer, Jewish agent, imperious blues diva, Amos and Andy trombonist and bassist, cynical and self-educated pianist. Most of all, Levee, the young trumpeter whose own music is in the future, as definitively as his hatreds have been formed by the violent incidents of his past.

Timothy Bond’s direction was marvelously taut, linear, detailed, and his cast perfectly assembled. I’ll refer you to the program for all the names, but I can’t fail to cite Kevin Kenerly, always memorable here (a brilliant sullen Romeo; a complex, near-pathological kid brother in Topdog/Underdog): his portrayal of Levee was funny, louche, driving, brittle, and finally eruptive. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom could slide into melodrama: his intelligence, which contains in addition the collective intelligence of the director and the entire cast, sends the play instead into the rank of great tragedy.

SO BEGINS — not quite — just about my favorite Shakespeare play, which we saw last night. We saw it a little over a year ago, done by the Los Angeles company A Noise Within in their small deep-thrust theater in Glendale: there it was poetic and romantic, the director’s attention concentrating on Shakespeare’s marvelous text.

Here in Ashland in the much larger Elizabethan Theater, open to the night sky and seating a much larger audience confronting a more conventional stage (though lacking curtain and proscenium), Peter Amster’s direction focussed on another aspect, almost an opposite one, of this rich and complex play: its clowning. Linda Morris was a fine, brash, good-hearted Viola, and Robin Nordli — last year’s Hedda Gabler! — was winning if sometimes ditzy as Olivia. But it is when Shakespeare (and Amster) send in the clowns that this production comes completely to life, reaching out into the big audience whose laughter often drowned out the cast.

Oddly, this was set up at the very beginning, when Michael Elich, as Orsino, speaks that marvelous line: If music be the food of love, play on... The line was overstated, loud, round, and slow, amusing Orsino’s attendants as much as the audience. Orsino is a difficult role to play, I think, central to the play, but not promiinently present; engaging, but not always sympathetic; romantic, but rarely convincingly so. If Mozart and da Ponte had made an opera of this play (oh how I wish they had) his role would have gone to the baritone who sings Don Giovanni. Michael Elich played the role here, and very well indeed (helped immensely, as was everyone, by Shigeru Yaji’s costumes), but in this production he directed your attention not to Olivia but to Sir Toby Belch, somewhat his counterpart at Olivia’s end of town. (For this play, like so many of Shakespeare’s, divides its setting into two camps.)

Robert Sicular was Sir Toby, and he elevated what is often an accessory role into a central one. I think Sir Toby stands often for the playwright himself — commenting on the other characters, the action, even referring, especially in this setting, to other plays in the canon. Dost think because thou art virtuous there’ll be no more cakes and ale? In which case Sir Andrew Aguecheek, wonderfully idiotic in Christopher DuVal’s performance, is perhaps many of us in the audience, standing on uncomprehendingly, blankly repeating bits of text back when spoken to, bumbling in foreign French, giving up, hiding from the constant onslaught of wit and repartee, which goes on whether he comprehends or not. And poor put-upon Malvolio, in Kenneth Albers’ rendition (which recalled his recent Lear from time to time), is of course Shakespeare’s satirical portrait of his rival Ben Jonson.

Altogether it’s a production of Twelfth Night to contemplate, consider, and enjoy. Not by any means the definitive production — but can there ever be an exhaustive interpretation of this play?

IN THE AFTERNOON we had seen quite a different play, August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Perhaps you know the argument: four musicians gather in a 1920s recording studio in Chicago, where they will back a blues singer, Ma Rainey. She’s late, held up by a traffic incident that’s escalated into a minor skirmish in the constantly present race war. Cracker recording engineer, Jewish agent, imperious blues diva, Amos and Andy trombonist and bassist, cynical and self-educated pianist. Most of all, Levee, the young trumpeter whose own music is in the future, as definitively as his hatreds have been formed by the violent incidents of his past.

Timothy Bond’s direction was marvelously taut, linear, detailed, and his cast perfectly assembled. I’ll refer you to the program for all the names, but I can’t fail to cite Kevin Kenerly, always memorable here (a brilliant sullen Romeo; a complex, near-pathological kid brother in Topdog/Underdog): his portrayal of Levee was funny, louche, driving, brittle, and finally eruptive. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom could slide into melodrama: his intelligence, which contains in addition the collective intelligence of the director and the entire cast, sends the play instead into the rank of great tragedy.

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

Cannelini, or however you spell it

A can of Italian white beans, a can of good tuna, a red onion sliced thin, a drizzle of olive oil, sage leaves if you remember them. One of the Hundred Great Recipes, and don't forget a glass of Pinot grigio.

Otherwise, it's just been too hot -- 115 degrees yesterday as we drove through Redding! -- and the international news too depressing. A week in Ashland should set things right.

Sunday, July 03, 2005

INDEPENDENCE!

THANKS TO ALL those heroic farmers, tradesmen, bankers, writers, and seamen who fought and argued and thought so passionately to win our independence, two hundred twentynine years ago, from the hated tyrants five thousand miles across the Atlantic.

How sad it is to see our own nation evolved through those two and a quarter centuries to be so like the empire we had to fight to gain our independence.

We watched interviews on the McNeill News Hour, Friday night, with Americans who were very recently fighting in Iraq. They spoke of the insurgents there in the same terms that the Redcoats used to complain of their enemies in the French and Indian War: they wear no uniforms, they strike and disappear back into their undistinguished context.

I don’t know if the News Hour will observe its usual schedule on Monday, that being July 4: if so, you can see that interview in full on that day; if not, perhaps the next. It’s provocative.

ON ANOTHER NOTE, there’s a significant piece in the current issue of Sierra, the magazine of the Sierra Club, in which Jonathan Rowe, director of the Tomales Bay Institute (http://www.earthisland.org/tbi) discusses the concept of the Commons. He writes about “The Common Good.” The idea began in the universal awareness that certain things, because of their transcendant importance to human life, could not be privately owned: at first, notably, pasturage and the spaces needed for publc gathering and communication — “the realm of life that is distinct from both the market and the state and is the shared heritage of us all.”

The concept of private ownership has been extended so far, in recent decades, that the concept of Commons has had to be extended as well: it now includes water, seeds, the atmosphere. In future years I believe the concept will extend to include what is now called “intellectual property,” that is, the universe of human thought, whether creative or analytical, that is necessary to produce both the technology and the wisdom that will be needed to deal with crises, both environmental and political-militaristic, that will otherwise threaten the very continuance of our species.

I recommend this article. As our forebears fought to maintain independence and self-suffiiciency and to protect them from distant imperiialists, our children and grandchildren are likely to find in tecessary to fight to reaffirm basic practical moral positions in the face of imperious profiteers at home. Jonathan Rowe’s article puts this in very clear perspective.

How sad it is to see our own nation evolved through those two and a quarter centuries to be so like the empire we had to fight to gain our independence.

We watched interviews on the McNeill News Hour, Friday night, with Americans who were very recently fighting in Iraq. They spoke of the insurgents there in the same terms that the Redcoats used to complain of their enemies in the French and Indian War: they wear no uniforms, they strike and disappear back into their undistinguished context.

I don’t know if the News Hour will observe its usual schedule on Monday, that being July 4: if so, you can see that interview in full on that day; if not, perhaps the next. It’s provocative.

ON ANOTHER NOTE, there’s a significant piece in the current issue of Sierra, the magazine of the Sierra Club, in which Jonathan Rowe, director of the Tomales Bay Institute (http://www.earthisland.org/tbi) discusses the concept of the Commons. He writes about “The Common Good.” The idea began in the universal awareness that certain things, because of their transcendant importance to human life, could not be privately owned: at first, notably, pasturage and the spaces needed for publc gathering and communication — “the realm of life that is distinct from both the market and the state and is the shared heritage of us all.”

The concept of private ownership has been extended so far, in recent decades, that the concept of Commons has had to be extended as well: it now includes water, seeds, the atmosphere. In future years I believe the concept will extend to include what is now called “intellectual property,” that is, the universe of human thought, whether creative or analytical, that is necessary to produce both the technology and the wisdom that will be needed to deal with crises, both environmental and political-militaristic, that will otherwise threaten the very continuance of our species.

I recommend this article. As our forebears fought to maintain independence and self-suffiiciency and to protect them from distant imperiialists, our children and grandchildren are likely to find in tecessary to fight to reaffirm basic practical moral positions in the face of imperious profiteers at home. Jonathan Rowe’s article puts this in very clear perspective.

Thursday, June 30, 2005

Authentic Argo

A friend sends the draft of a paper on authenticity. It relates to something that’s been preoccupying me for a while; let’s call it Separation Anxiety. I’ve been noticing that increasingly in the last few months; I suppose it’s an inevitable part of aging.

Equanimity is better than anxiety, don’t you think? But maintaining equanimity in the face of approaching death is a difficult matter. (Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think my own death is right around the corner. But all around me there are friends and acquaintances brushing up against it, and it can’t help but be on my mind.)

The human preoccupation with Death — or, more often in our culture, evasion of it — is a logical result of the preoccupation with Individuality. I think this may be a key factor in our puzzlement at the willingness of religious fanatics to die for their various causes. We Americans cannot really comprehend the minds of suicide bombers, as I imagine the ancient Romans must have been perplexed at the complacency of many early Christians as they went to martyrdom (though self-death in battle was, I’m told, part of The Roman Way).

But I digress, as blogs so often do. What I’m thinking about this morning is Authenticity, which has always seemed to me a function of Place. Separation anxiety has to do with losing our place, because we identify with our place — our extended Place, which includes our family and friends, our home and things, our ideas and opinions.

Authenticity has to do with our objectification of Place, our hope, probably sentimental, that an expression of Place can continue even from one generation to the next.

This brings us to Sustainability, which is the gathering of attention and use toward the realization of that hope.

On the social level, now famously global, Sustainability requires heroic political measures. I’ve argued that these measures must begin locally and ripple outward.

And I think the social and political drive toward Sustainability is an outward counterpart to an equally desirable inward drive: toward Equanimity.

Authenticity and sustainability and equanimity are three faces of a single thing, and have to do with equilibrium. There are two constants whose tension defines the public or political neurosis of our time, and the individual separation anxieties bedeviling so many of us. One is the apparently universal human desire for Individuality and with it security. The other is Heraklitus’s famous statement: The only constant is change.

Equanimity, on a personal scale, must have something to do with willingness to modify individuality to accept the inevitability of change. Sustainability, on a political scale, requires a similar discipline when dealing with environmental factors.

The result is authenticity, a human expression of Place as it responds to Change. It occurs to me that the ancient expession of this riddle is Jason’s boat, the Argo, which remains always the same boat though over the years every one of its parts has been replaced.

Equanimity is better than anxiety, don’t you think? But maintaining equanimity in the face of approaching death is a difficult matter. (Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think my own death is right around the corner. But all around me there are friends and acquaintances brushing up against it, and it can’t help but be on my mind.)

The human preoccupation with Death — or, more often in our culture, evasion of it — is a logical result of the preoccupation with Individuality. I think this may be a key factor in our puzzlement at the willingness of religious fanatics to die for their various causes. We Americans cannot really comprehend the minds of suicide bombers, as I imagine the ancient Romans must have been perplexed at the complacency of many early Christians as they went to martyrdom (though self-death in battle was, I’m told, part of The Roman Way).

But I digress, as blogs so often do. What I’m thinking about this morning is Authenticity, which has always seemed to me a function of Place. Separation anxiety has to do with losing our place, because we identify with our place — our extended Place, which includes our family and friends, our home and things, our ideas and opinions.

Authenticity has to do with our objectification of Place, our hope, probably sentimental, that an expression of Place can continue even from one generation to the next.

This brings us to Sustainability, which is the gathering of attention and use toward the realization of that hope.

On the social level, now famously global, Sustainability requires heroic political measures. I’ve argued that these measures must begin locally and ripple outward.

And I think the social and political drive toward Sustainability is an outward counterpart to an equally desirable inward drive: toward Equanimity.

Authenticity and sustainability and equanimity are three faces of a single thing, and have to do with equilibrium. There are two constants whose tension defines the public or political neurosis of our time, and the individual separation anxieties bedeviling so many of us. One is the apparently universal human desire for Individuality and with it security. The other is Heraklitus’s famous statement: The only constant is change.

Equanimity, on a personal scale, must have something to do with willingness to modify individuality to accept the inevitability of change. Sustainability, on a political scale, requires a similar discipline when dealing with environmental factors.

The result is authenticity, a human expression of Place as it responds to Change. It occurs to me that the ancient expession of this riddle is Jason’s boat, the Argo, which remains always the same boat though over the years every one of its parts has been replaced.

Monday, June 27, 2005

Ascraeumque cano...

...Romana per oppida carmen. (Georgics, II, 176)

A dear friend urges me, now that I’ve read Cato and Varro, to turn again to Virgil and the Georgics. I know I have the Slavitt translation around here somewhere... where? Where do the damn books go, the favorite ones, the ones you’d never lend or sell? Hesiod’s Works and Days, and Virgil’s Georgics and Eclogues, both in the Slavett translation... nothing easier to find on the shelf .. I see how big they are, their white spines with the “handwritten” lettering: where the hell are they?

What does turn up, at least, is the C. Day Lewis translation, in the bilingual edition (Doubleday Anchor Original paperback): and when I open it, at random, that’s the line that jumps out at me:

Ascraeumque cano Romana per oppida carmen...

And I see it again on the blackboard where my enthusiastic TA in Latin wrote it out, with the strokes and horseshoes marking long and short syllables, and I remember his excitement at the line, long, long short short longshort /

- - uu - u / u - u u - uu - u

I’ll sing of farm things throughout Rome and her towns and her cities

C. Day, writing twenty years after the end of World War II, says:

How idealistic; how quaint. How very English, recalling Prince Charles’s speech to the assembled farmers and stockbreeders last October at the Slow Food-produced conference of smallholders from around the globe, when he addressed this very topic — though in a tone not quite so optimistic, closer in fact to despair.

Since Lewis wrote those lines industry, agriculture, indeed virtually all of modern civilization has become not rural-urban but urban-global. And if China can think of buying Unocal today, there’s no reason to believe she won’t soon be offering to buy General Foods, Monsanto, Archer Daniels Midland.

Is it just the Berkeleyan in me that thinks the only path of resistance is increased opting-out? I was encouraged a week ago to find, in Wisconsin, vital and apparently healthy producers of sustainably raised, chemical-free (or nearly so), seasonable products of local terroir eagerly sought by thousands of purchasers at Madison’s Sunday morning farm market. But of course this is a very special clientele: educated, discriminating, relatively prosperous. Privileged, in a word.

What must be done next is to extend these “values” beyond that circle: to the young, to the blue-collar, to people of color. I think such action must begin locally, starting in the rich suburban farms near college towns, demonstrating their economic viability, their healthfulness, and the joys of their flavors and fascinations to their own neighbors.

This is happening here in Healdsburg on Saturdays and Tuesdays; in Windsor on Sundays; in Sebastopol also on Sundays. There are farm markets in Santa Rosa and San Rafael and, famously, in San Francisco’s Ferry Building Such optimism can be contagious, I think. But then I’m perhaps as innocent as C. Day Lewis.

And I can’t find those Slavitt translations anywhere. Or my desk glasses either.

A dear friend urges me, now that I’ve read Cato and Varro, to turn again to Virgil and the Georgics. I know I have the Slavitt translation around here somewhere... where? Where do the damn books go, the favorite ones, the ones you’d never lend or sell? Hesiod’s Works and Days, and Virgil’s Georgics and Eclogues, both in the Slavett translation... nothing easier to find on the shelf .. I see how big they are, their white spines with the “handwritten” lettering: where the hell are they?

What does turn up, at least, is the C. Day Lewis translation, in the bilingual edition (Doubleday Anchor Original paperback): and when I open it, at random, that’s the line that jumps out at me:

Ascraeumque cano Romana per oppida carmen...

And I see it again on the blackboard where my enthusiastic TA in Latin wrote it out, with the strokes and horseshoes marking long and short syllables, and I remember his excitement at the line, long, long short short longshort /

- - uu - u / u - u u - uu - u

I’ll sing of farm things throughout Rome and her towns and her cities

C. Day, writing twenty years after the end of World War II, says:

The fascination of the Georgics for many generations of Englishmen is not difficult to explain. A century of urban civilization has not yet materially modified the instinct of a people once devoted to agriculture and stockbreeding, to the chase, to landscape gardening, to a practical love of Nature... It may, indeed, happen that this war, together with the spread of electrical power, will result in a decentralization of industry and the establishment of a new rural-urban civilization working through smaller social units. The factory in the fields need not remain a dream of poets and planners: it has more to commend it than the allotment in the slums.

How idealistic; how quaint. How very English, recalling Prince Charles’s speech to the assembled farmers and stockbreeders last October at the Slow Food-produced conference of smallholders from around the globe, when he addressed this very topic — though in a tone not quite so optimistic, closer in fact to despair.

Since Lewis wrote those lines industry, agriculture, indeed virtually all of modern civilization has become not rural-urban but urban-global. And if China can think of buying Unocal today, there’s no reason to believe she won’t soon be offering to buy General Foods, Monsanto, Archer Daniels Midland.

Is it just the Berkeleyan in me that thinks the only path of resistance is increased opting-out? I was encouraged a week ago to find, in Wisconsin, vital and apparently healthy producers of sustainably raised, chemical-free (or nearly so), seasonable products of local terroir eagerly sought by thousands of purchasers at Madison’s Sunday morning farm market. But of course this is a very special clientele: educated, discriminating, relatively prosperous. Privileged, in a word.

What must be done next is to extend these “values” beyond that circle: to the young, to the blue-collar, to people of color. I think such action must begin locally, starting in the rich suburban farms near college towns, demonstrating their economic viability, their healthfulness, and the joys of their flavors and fascinations to their own neighbors.

This is happening here in Healdsburg on Saturdays and Tuesdays; in Windsor on Sundays; in Sebastopol also on Sundays. There are farm markets in Santa Rosa and San Rafael and, famously, in San Francisco’s Ferry Building Such optimism can be contagious, I think. But then I’m perhaps as innocent as C. Day Lewis.

And I can’t find those Slavitt translations anywhere. Or my desk glasses either.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Frank Lloyd Wright Duplexes

These duplexes, many now needing a little attention, were built in 1916 as low-income housing in what had until then been a celery farm on the outskirts of Milwaukee. Photo: C Shere, June 2005

Thursday, June 23, 2005

Mixed use urbanity

A friend asks me to think about town planning, knowing my enthusiasm for the villages and provincial cities in Holland, where we plan to spend two or three weeks again this fall, walking from one to the next. He lives in Healdsburg, and like us is concerned about the changes there.

He suggested I blog about town planning, and that I use last week’s trip to Chicago and Wisconsin as a sort of trial run. It didn’t work out quite that way, as you’ll have seen. Chicago and Milwaukee have little in common with Healdsburg. They may have things to teach San Francisco and San Jose, but the problems and opportunities of a town of 9,000 are a very different matter.

Still there were urban impressions on this trip that may be worth passing along, especially today, in the wake of what seems to me a truly horrendous decision by the Supreme Court in the New London decision. It’s painful to find Rehnquist, Scalia and Thomas on my side, for a change, but there it is: the “liberals” on the Court ruled that the city of New London may seize houses that have been occupied by a family for generations, pay the occupants market value, and turn the property over to private developers, because the resulting hotels, shops, and offices will contribute to “the public good.”