SO MANY THINGS going through my mind, it was difficult to sleep last night. Shortly before turning in I received a message from an acquaintance of forty years ago, lost track of since, not even sure where he is or what he does with himself; he published a book of poetry that greatly impressed me back then, and recently through the magic of the Internet and of second-hand bookshops someone found a copy, read it, and commented on it at length.

He wrote me:

i recently was contacted by a young lady who writes and teaches in France. She discovered a copy of Tesseract in a bookstore last year and wrote a review, posted to her website:http://spindrifter.webs.com/apps/blog/entries/show/1523079-the-scattered-sea-of-james-monday-s-poetry

i thought you would enjoy reading it.

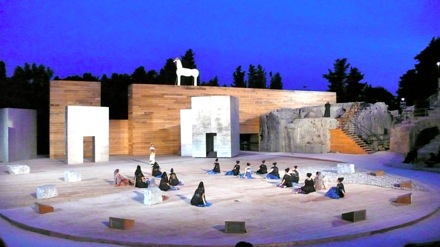

and he is right, I do enjoy reading it. His book, Tesseract, comes back to me; I see it on the bookshelf in the study and wish it were at hand, a little, though instead of reading it I am about to download Euripides' play Hippolytus because we are seeing it, or an adaptation of it, in Syracuse tomorrow night.

What Spindrifter writes about Tesseract is interesting; Monday's had the luck, good or otherwise, to see his book — written and self-published, I believe, back in the day when you had to be a typesetter to self-publish honorably — fall into the hands of someone programmed to respond to its central conceit, the fourth dimension.

(It enchanted me, back then, for the same reason; at the time I was busy constructing three=dimensional models of the regular polyhedrons, and wishing I could somehow project them into another dimension. I suppose it was writing music that resolved that urge.)

I was thinking about this last night as I was trying to sleep, or rather my mind was thinking about it, I was trying not to think about it, when another thing came into mind: speculation. Spindrifter is a speculator, and so am I. Speculators are thought of as people who take risks with money or property, but what they really do, and by "really" I mean etymologically, is look at things, look at themselves looking at things. And this is what this Italian journey has led to.

I mean, look: There were people living in the neighborhood of Agrigento perfectly successfully, eating fish mostly, making what we'd call rather crude pots and little votive sculptures out of clay, worrying about the weather and the kids; and then the Greeks decided they liked the place, and moved in, shouldered the natives aside (while apparently respecting their spiritual sites), built houses, then temples, then museums I think; before long there was a real "civilization", then international trade, then disagreements and uprisings and war and probably domestic discontent; finally a cataclysmic earthquake as if Nature wanted to put the brakes on the whole thing.

Now let's think about my country, California, where there were people living in the neighborhood of San Francisco perfectly successfully, eating fish mostly, making what we'd call rather crude pots and baskets and things…

You get the point.

<hr>

THIS MORNING AT breakfast in our hotel we were discussing the day's activities, and next week's, and I was looking at the notes I'd prepared on my iPad, when the deskclerk came over to the table, as well as the barista who'd made my cappuccino, and excused themselves, and asked Is that an iPad? We don't have them here yet… and I said Yes, it's an iPad, and showed them its tricks, and handed it to them; the deskclerk took it gingerly and touched a couple of icons and showed the barista how little it weighed, they stood there hefting it and commenting on it; even Lindsey was entertained by how cute the scene was.

A week or so ago in Palermo we were having a cappuccino for breakfast at a bar while our clothes were whirling about in the lavanderia Self; the barista had gone off somewhere, and an extremely handsome young man came in and said to me fammi un cappuccino così per favore, make me a cappuccino like that one please. I looked at him blankly: Scusa? He repeated himself; then when the barista showed up excused himself with great embarrassment, saying he'd thought I was the barista, I who look not at all Italian as far as I can tell.

The young man turned out to be a Romanian from Bucharest, here to better his life, and if good looks and careful dressing have anything to do with it he need only improve his observational skills to go places. We shared a laugh over his mistake, and I told him I'd traveled through his country nearly thirty years ago, before he was born, It was very different then, he said, But it has a long way to go.

<hr>

Yesterday on the drive here from Agrigento we took the two-lane country road, SS 115 I think it is, with lots of hairpins even along the coast; passing is extremely difficult because the road is so narrow and the visibility often so poor. Cars here tend to go as quickly as possible; no one respects the frequent 50 km/h signs (just as no one stops at stop signs; they're only there as counsel, not imperatives). What slows you down? Big trucks, little trucks, the occasional maddeningly slow old man in a cinquecento, a German tourist in an RV with a motorcycle on the rear bumper (that's how you know he's German, the Dutch have bikes), an occasional longdistance cyclist, the inevitable three-wheel pickup-like vehicles.

And at one point an old man was walking along the shoulder, if there'd only been a shoulder, bent a little at the waist, reading something held in his two hands before him, around his belly a strap going back on either side and attached to what seemed to be one of those suitcases on wheels that people roll through airports.

We've seen more than one peddler. In paintings in the Prado you see them in former centuries, with pushcarts or simply baskets, selling ribbons, candies, handkerchieves, fruits, little birds, God knows what. Today they offer telephone batteries, lottery tickets, fruits, wind-up toys, God knows what. They sometimes even come through restaurants when you're trying to relax over supper, though we've only seen that once or twice, and then in Palermo.

Italian bathrooms continue to interest me. Today's hotel is the first to have provided a label over the pull-string in the shower: EMERGENCY. (You no longer see those strings over the bedstead; probably too many tourists pulled on them thinking to turn off a light rather than arouse the emergency staff. Nor for that matter are there any crucifixes over the bed any more. We live in liberal times.)

Virtually every toilet we've seen has had its own idiosyncratic method of triggering a flush mechanism, and most, no matter how luxurious the appointments otherwise, have had loose, mismatched, or broken seats. In the cafés of course there are rarely any seats at all, and I always think of my friend Mac who was surprised that anyone would want one, since as he thinks they are all only a source of dread disease.

Today we had a fine lunch; you'll be able to read about it, I think, over at Eating Every Day. When I asked for the check, though, very uncharacteristically it was not forthcoming. Instead, after a few minutes, the waiter asked if I wouldn't like a coffee. No, I said, the check. Non vuole un caffè? Oh, okay, yes, why not, I'll have a coffee first. And the coffee was absolutely excellent, as has generally been the case here in Sicily. Afterward, though, I still couldn't get the check.

When I stopped at the cash register on my way back from some research in a back room I asked for it again, and the waiter — who was also the cook — pointed at his computer display and said that non funziona. Ah. Computer's down; can't print out a check. Even a tiny trattoria depends on these things these days. (The government practically requires it, since by law you must be given a detailed receipt, and you must carry it with you from the restaurant a given and not unsubstantial distance, in case you have to prove to someone that you have indeed paid for your meal.)

In the end the poor fellow had to consult his menu to find out how much each item cost, write them down laboriously on a notepad, add up the figures, and then announce: Twenty. I had only a fifty. Però, signor, non ha un di venti? Waving his hands together and apart as if smoothing out an unruly invisible sheet. Fortunately Lindsey had one, and we escaped.

Photos: Campania, including Caserta, Herculaneum, Amalfi, and Paestum:gallery.me.com/cshere#100239

Palermo: gallery.me.com/cshere/100241

Tràpani, Erice, Segesta and environs: gallery.me.com/cshere/100275

Mozia: gallery.me.com/cshere#100283

As always, our meals are recorded at Eating Every Day