FERE ALIQVVBI HIC ILLVD SCIOI'

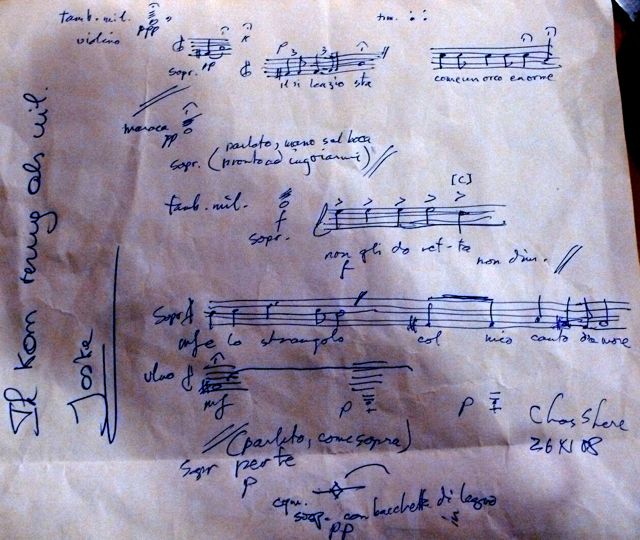

VE BEEN MULLING OVER this music for a couple of months now, Pierre Boulez's cycle

Le Marteau sans maître; I write about it today quite unprepared — for one thing I can't recall where I put the score — but under some urgency, as a performance is

scheduled next Monday in San Francisco, and it doesn't hurt to call some attention to it.

(Alas I won't be able to hear it: I'll be in Los Angeles.)

I've been thinking about the piece because of a strange string of coincidences. Six or seven weeks ago, just before we left on a longish trip to Italy, we had dinner with a couple of friends in Healdsburg. Richard gave me a little bundle wrapped in paper, a cube whose proportions looked oddly familiar. At the bottom, tied to the package but not within its wrapping paper, was a booklet. The package turned out to be a stack of identically proportioned miniature scores in the familiar Eulenberg yellow covers, mostly standard-rep pieces. The "booklet," however, was the first edition of the miniature score to

Le Marteau sans maître.

Even more exciting, it had Gerhard Samuel's signature on the cover; and inside its pages I found the program to the performance he conducted in Berkeley, at the University of California, in 1962. I had heard that performance: the exotic sounds and elusive construction of the piece had been an epochal moment in my awakening to music. Without exaggeration I would have to say that that concert, with two others — an all-Webern concert, also at UC, a few years earlier, and a Cage-Tudor concert in San Francisco a couple of years later — was what led me to music.

Not having a recording of

Le Marteau sans maître on hand I turned to the Internet, downloading the Lorelt re-release, with mezzosoprano Linda Hirst and the Lontano ensemble conducted by Odaline de la Martinez. I listened to it casually two or three times before leaving for Italy in late October.

I just listened to it again, this time in a different context: a letter arrived today from another friend who writes about Debussy and Berlioz and the impact on their music — as he suspects — of their language, whose supple scansion imparts a completely different sound, or aural mentality, I might say, than that of Germanic composers of their time. Douglas is particularly keen on this subject: he's spent a number of years investigating the metrics (

and melodics) of classical Greek poetry; his Latin is also up to subtle investigations; and he loves the free expressivity of the poets of those languages, so unlike the dum-de-dum (as he puts it) of poets working in English and, especially, German.

I think, but have no reason to — undoubtedly this is sheer projection — I suspect that Boulez composed this music poised between contemplation and invention, but always with the sounds of his ensemble and the sounds of Char's poems at the front of his mind. Since we're overstating cases, let's not be afraid of bold generalizations: the Germanic mentality is fond of measuring things, and drawn to substances; the Gallic mentality is more likely to contemplate things, without touching or manipulating them you might say, and is drawn to surfaces.

(I suspect there's a lot to be discovered in considering the intersections of the Greek-Roman and German-French dualities, two scales whose opposite ends declare changing allegiances to those of their counterparts. But I'm not going further with that at the moment.)

If you don't know

Le Marteau sans maître, you're not going to hear it, or for that matter learn much about it, here. You have to

hear it. The nine sections, totalling a little over half an hour, set for various combinations an ensemble of only six musicians (voice, alto flute, viola, guitar, vibraphone-xylorimba, percussion), has a supple, lyrical, sinuous, glittering appeal; the composer György Ligeti called it "feline."

The music is relentlessly complex on the page. I telephoned Anna Carol Dudley, who sang it in that 1962 performance, and she confirmed there'd been at least fifty rehearsals. She spoke of the music as being unnecessarily difficult on the page: it goes by so fast, and has so many notes and such complex rhythms, that in the end an audience can hardly know whether a performance is accurate or not.

But that has nothing to do with

listening to the music. It is, instead, a testament to the composer's attitude toward craft, to his procedure, and his awareness of his historical moment as it intersects with his own individual responses to the material he's working with — those six musicians and René Char's Surreal poems.

Le Marteau sans maître is the subject of an unusually intelligent and attractive

discussion on Wikipedia. (Wikipedia's entry on

Boulez is equally intelligent.) Tony Haywood contributes a thoughtful

review of the Lontano recording on the Internet, too, geared more to the layman; Wikipedia's extensive source citations will lead the really curious researcher much further.

Le Marteau sans maître was influential in its day, half a century ago; more so in Europe, of course, than in the United States, where "difficulty" is quickly evaded. One of the ironies of the world of concert music is that the standard repertory of Beethoven and Brahms has been hammered into popularity by the music press; the same forces have sneered at the complexities of Modernist music from Schoenberg to Stockhausen, and recoiled from what it sees as the eccentricities of "mavericks" from Satie to Scelsi.

A gullible public has been trained to mistrust and dislike the music it rarely has a chance to hear. A week of

Le Marteau sans maître, the Modern Jazz Quartet, a little bit of Gerry Mulligan and even Chet Baker, early Stockhausen pieces like

Kontra-Punkte (which I'll hear next Tuesday in Los Angeles) and

Refrain, and Cage's music from the mid-1940s through the 1950s, and anyone with an open mind and a receptive ear would be persuaded that this music is, in fact, the Debussy and Satie of our own time (or a decade or two ago). We've been deprived of a great deal.

SOME LITTLE WHILE ago, in July 2007, I wrote

SOME LITTLE WHILE ago, in July 2007, I wrote

Chamechaud, seen from the north, 1976

Chamechaud, seen from the north, 1976