Friday, March 28, 2014

Three Plays in Ashland: The Cocoanuts; The Tempest; The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window

FOR YEARS WE'VE SUBSCRIBED to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the impressive repertory company in Ashland, where ten or twelve plays are given over a season lasting nearly nine months. In addition to Shakespeare, the repertory these days runs through primarily American plays, including a number of new plays, a few revivals, and, recently, a musical or two.

We've been attending these plays so long we've seen the artistic direction change generations, and — getting on ourselves, and perhaps not as generous about change as we might be — I've been concerned about some of the change. I miss the international rep — Ibsen and Chekhov seem to have faded away.

I'm restless about some of the Shakespeare productions, which sacrifice the Bard's poetry too often to gimmicks apparently meant to make his substance more relevant, more accessible, to contemporary audiences. (The low point was a Troilus and Cressida set in the recent American-Iraqi war.)

Not all the new plays have seemed worth the effort to me, though some have offered interesting contemporary foils to Shakespeare — Tony Taccone's Ghost Light, for example, and Robert Schenkkan's plays on the Lyndon Johnson presidency. And some of the musicals have been sadly compromised by more of that gimmicky "updating": here the low points have been The Pirates of Penzance and My Fair Lady.

So this season we've bought tickets to only five of the eleven plays — only to find, this last week, that the first three of our choices were really very good, well worth the price of admission. If only I could find reviews I can trust of the remaining shows, I might be tempted to give them a chance!

The three plays we saw couldn't be more different. The Cocoanuts, with book by George S. Kaufman and music and lyrics by Irving Berlin, was written in 1925 for the Marx Brothers, who improvised or otherwise contributed a good deal of its shtick. Any revival faces the problem of those brothers, of course: they need to be recognizably Marx, but should go beyond simply presenting impressions. This is where the tight ensemble and even talent of the OSF company can really shine, and we were more than happy with Mark Bedard, Brent Hinkley, John Tufts, and Eduardo Placer in for Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and, yes, Zeppo (the romantic lead).

The Cocoanuts is vaudeville brought to the somewhat more legitimate theater, and the musical component is fairly important. Jennie Greenberry was a fine soubrette as Polly Potter, the female lead, with a really attractive voice and sharply defined comic acting; and K.T. Vogt did well with the heavy role of her mother. Kate Mulligan and Robert Vincent Frank were just as detailed and engaging as the villains, Penelope Martin and Harvey Yates; and the rest of the cast were up to the marks as well.

The play alternates between sweetness and zaniness, and David Ivers's direction managed that alternation with apparent ease, profiting from Richard Hay's design and Meg Neville's wonderful costumes. I'd love to go back for another look at the show later in the season, to see how they keep it so fresh and funny.

The Tempest saw a fine, thoughtful production in Ashland in 2002, when Penelope Mitropoulos took the lead role, changing Prospero's gender as Prospera, and bringing new, larger resonance to Shakespeare's theme of reconciliation through understanding, patience, and forgiveness.

Then in 2007 the play suffered, I thought, from a more equivocal, tentative production centering on a lead actor who — in spite of repeated successes in other roles here over the years — seemed uneasy with his assignment and uncertain as to the play.

This year the play again hesitates with its lead. Denis Arndt is a diffident, sometimes almost playful Prospero, relying on Daniel Ostling's design, Alexander Nichol's marvelous lighting, and Kate Hurster's often powerful Ariel, rather than on his own voice and stage presence, for the brittle, mercurial force and inventiveness of his magic.

But the production really works well. Shakespeare's familiar contrasting levels of society are acted and directed thoughtfully and effectively but also dramatically, even entertainingly. The Italian nobility, the mariners, above all Stephano and Trinculo (Richard Elmore and Barzin Akhavan), all address Shakespeare's lines, the plot's requirements, and the audience's engagement.

Wayne T. Carr was a fine Caliban, I thought, his resentment sympathetic and his role ultimately reclaimed. Kate Hurster's Ariel was perhaps a bit too big in its conception, but effective and often beautiful. Like her father, Miranda (Alejandra Escalante) flirted with diffidence. In the end, though, they seem like contemporary Americans looking on as their alter egos enact this great play, bringing yet another layer of meaning to the stage.

I wish I had time, patience, skill, and scope to write about Lorraine Hansbury's The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window with the insight and substance the play deserves. It's a big, important, powerful play, addressing serious issues both societal and individual. It is narrative theater at its best, I think, set on a plot with beginning, middle, and end, presented through characters who are sympathetic, understandable, now and then surprising. And while the mood is generally serious and occasionally flirts with tragedy there is humor and affection.

The play was badly received at its opening in 1964 — it was too big, too "difficult" for the commercial entertainment critics. Hansbury was already dying (pancreatic cancer); if there were any thoughts of revisions, there was no strength to achieve them. I think some judicious cutting would improve the play: a long drunk scene seems perilously like a bitter survey of postwar absurdist theater.

But Juliette Carrillo's direction makes it clear that this is a perfectly workable, stageworthy play, and the cast pretty well nailed their assignments: Ron Menzel in the title (lead) role; Sofia Jean Gomez as his wife Iris; Erica Sullivan as her brittle, aloof sister Mavis; Vivia Font in the small but pivotal role of the third sister, Gloria; Armando McClain, Danforth Comins, and Benjamin Pelteson in the significant roles of Alton the (mixed-race) friend, Wally the politician, and David the upstairs gay playwright. We saw Jack Willis as the abstract expressionist down the hall; he was just as solid, detailed, and engaged an actor as all the rest.

As you can perhaps tell by the capsule descriptions in the previous paragraph, Hansbury weaves plenty of strands into this dramatization of social issues of midcentury America. It was fascinating to come to know the play just after a reading of John Steinbeck's last novel, The Winter of our Discontent, written just a few years earlier. Both writers deal with corruption; both are aware that it is an inevitable and perhaps even a necessary component of the social human condition, as the human reach for ideals always stretches beyond the grasp of the compromises without which daily life seems unbearable and impossible.

Saturday, March 22, 2014

A provisional commentary on Virgil, John, and Lou

|  |  | |

| Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) | John Cage (1912-1992) | Lou Harrison (1917-2003) |

In 1965, I think it was, Lou brought Virgil Thomson to our Berkeley apartment, on Francisco Street, for conversation, and from then on both men were occasional friends, I suppose you’d call them — Lou lived in Aptos, Virgil in New York; I was working double-time at KPFA and trying to compose on the side, not to mention keep the car running and the plumbing in line, all those things you do when you’re raising a family on $75 a week in a one-bedroom duplex, studio in the basement.

Chez Panisse opened in 1971, and it wasn’t long before Virgil came to dinner. I remember his liking Lindsey’s crème anglaise, complimenting her on how little cornstarch she’d used in it. Alice was shocked: Oh no, she said quickly; there’s no cornstarch in that crème anglaise. Lindsey smiled quietly: there was a tiny bit of cornstarch in it; subsequently she worked out a method that dispensed with it entirely.

We never went to New York, and still don’t, not having formed the habit. But Lindsey spent a few days there every few years on business, and when we were there we always visited Virgil in his rooms at the Chelsea Hotel. We talked about mutual acquaintances, about the old days, about Mozart, about criticism — I was by then working as an art and music critic, and was interested in that often-reviled and usually badly practiced profession.

By the early 1980s we knew John Cage well enough, Lindsey and I, to be on a first-name basis. In that decade I was working on a series of composer’s biographies for Fallen Leaf Press: I completed the first, on Robert Erickson, and got halfway through the next, on Lou. I was projecting one on John, too, and visited him a couple of times in his New York apartment, helping him make our lunch, talking about Duchamp, about Buddhism, about cuisine, about criticism.

I dropped the book about Lou after about 50,000 words, when I’d brought him up to his fiftieth year, when he was well settled with Bill Colvig, reasonably accepted in his corner of the music world, and had begun dedicating himself to gamelan, a music that didn’t interest me. By then it was clear Lou would not need my help in being presented to the wide world; that was well begun. Even less would John need a biography from me: a number were already in preparation as he approached his eightieth year.

Serious biography of this sort requires detective work, solid musical analysis, real focus, and discipline — all qualities I have little familiarity with and, in fact, little enthusiasm for. Besides, unlike Erickson, both Lou and John had lived within a social context I knew nothing about. Most of all, I very much liked both of them, and treasured them as friends and colleagues, a relationship I sensed would be endangered were I to continue further in a biographer’s role.

Lou and Bill visited us up here on Eastside Road a couple of times, and we continued to see them now and then in their Aptos house. (I remember one visit, when I was examining their house more attentively than usual, and Bill noticed. We were then planning our own house. I asked Bill whether he thought I should frame it in two-by-fours, the conventional approach, or two-by-sixes. “How long do you want to live in it?”, he responded; and we framed it in two-by-sixes.)

We saw Virgil and John, or Virgil or John, every couple of years, on those New York visits, or occasionally when one or another was in the Bay Area. If it was John, well, he was always busy, and we saw him in passing. He and Virgil were quite different in that respect: John was focussed, dedicated, disciplined, driven; Virgil was retired, sociable, at ease. I must say I preferred his style, though I respected and envied the other’s production.

The last time we visited Virgil at the Chelsea was a year or two before his death. He was quite old — he died in 1989 — but he was reasonably healthy as far as we could see. He mentioned that his sister had died at the age of 94, and he was certain he would not outlive her, and he turned out to be correct: he was two months shy of that age. I asked him if there were any way he could be reconciled with John. Not quite in those words, I suppose, but close. I was thinking about the idiotic rift that had set in between Satie and Debussy; how Debussy had died without seeing Satie again, and there was something in the Debussy-Satie relationship that had always rhymed, so to speak, in my mind, with the Thomson-Cage relationship. So many hours working in the trenches together, so many “values” in common, so much good conversation and shared experiences, all thrown away over some momentary thing. Virgil was not interested: John had gone his own way. I think perhaps in the end the hardest thing for Virgil was the progress, if you can call it that, of musical Modernism, away from his own day, into areas for which he had no interest, which were simply not to his taste, as gamelan is not to mine.

That same summer I saw John in his apartment. We had lunch together. We shelled peas, I think it was, or beans, and laughed at the cat on the catwalks, and talked about one thing and another. My problem with such interviews was always that there were so many things unsaid, because we both knew them, and agreed about them, why discuss them?

I did mention Virgil, though, and wondered why they wouldn’t speak. John was obstinate. The least you can ask of people, he said, is loyalty.

Certainly two events fed this feud. One was the early life-and-works book about Virgil, published as Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, Publisher; 1959). The book is published as having been written by Kathleen Hoover (the Life) and John Cage (the Music). A number of rumors fly around the book: John wrote it all, Virgil didn’t like the Life section and assigned it instead to Hoover. Or: Virgil wrote it all, and assigned the credits away to mask self-promotion. Or Virgil extensively re-wrote passages. I hate waspishness, and you deal with a certain amount of that when you negotiate these waters. In any case, it’s impossible to get to the bottom of such things; there are many truths.

The other event was Virgil’s review of whichever piece it was of John’s, I forget now, either 4’33" or the Variations (if that’s what it was titled) that involves a number of radios, that pushed John’s musical ideas beyond the threshold of Virgil’s limits — beyond, I mean, what Virgil’s sensibility and training allowed him to consider musical.

As late as 1962, in the introduction to the Peters Edition catalog of his music (called, simply, John Cage), John gracefully thanked Virgil (along with Peter Yates) for his understanding criticism. Criticism is at the center of the Virgil-John situation, and indeed to the Virgil-John-Lou group, to which in all humility I would add, at times, myself. I have always cherished and often cited the late Joseph Kerman's memorable, terse definition of the practice: "the study of the meaning and the value of art works." (Contemplating Music: challenges to musicology, Harvard University Press, 1986).

Virgil, John, and Lou, with a few others — Peggy Glanville-Hicks among them — created a community of criticism in that very sense, under Virgil’s direction, at the old New York Herald Tribune, in the years following the end of World War II. I don’t have patience to go further here into the extraordinary ferment of intellectual and artistic energy and knowledge present then and there: it was a moment like Paris, 1911-1928, or Vienna, 1770-1820. Such moments cannot be forced; they can only be exploited, and Virgil Thomson had the perfect intelligence and sensibility to understand that, and contribute further to it.

But criticism has its negative aspect, particularly when considered as it affects individuals, whether they are practicing it or responding to it. The Herald Tribune Virgil group, to call it that, comprised composer-critics. Who better to respond to music than a musician? But pride and sensitivity are easily involved, and the biographical results can be sad to contemplate.

Sunday, March 16, 2014

Apologia pro bloga sua

I am drawn particularly to Daniel Wolf's always intriguing Renewable Music. The other day he put a long post up on Facebook. I repost it here — I hope he won't mind — adding paragraphing to make it a little friendlier to my aging eyes:

When I started my blog, it was just supposed to be a sampling from the kinds of notes and observations I write while composing. Then the public nature of the beast got me to twisting the writing style in a more conventional journalistic or even scholarly style.I repost the comment to take heart about my own predicament, or position, or something — lack of focus, inconsistency of style, uncertainty as to audience. (Not his second paragraph, thank heaven; I've been spared that; also not "ancillary to my composing", as I've largely retired from that.) When I read my own writing from one or another of the books I've published in the last few years, I'm generally pleased enough: but the writing on these blog posts almost always troubles me for its inconclusiveness. I don't mind disjunction or allusiveness or even periphrasis, but irresoluteness is not a quality I admire, least of all in myself. Still I will soldier on, boat against the current…

(People started sending me all sorts of SWAG, asking me to mention their work or even review it, although I have no critical ambitions, let alone, talents whatsoever, which I would patiently explain. (Then people would get angry with me, sometimes virulently, for not mentioning or reviewing the materials they sent me.))

Some journalists and scholars can write wonderfully within the parameters of their genres, but my own attempts at writing in those styles were half-hearted, labored, and dull and, thankfully, didn't last long, as I realized that, as a composer, I had the license _not_ to write conventional prose, but rather could be, indeed ought to be, more inventive, and if not inventive, as least more of myself, even if that pushed some eccentricities into play.

In general, and though my thinking processes are certainly flawed in one way or another, I try to capture the way I actually think these things through, while working on my music. Sentences, breezily beginning with "And"s or "So"s can run long or fragment, often broken into phrases with comments and extensions and exceptions divided by ,s and ;s and between —s and ()s and []s (some of those within several layers of brackets, a habit for which reading Roussel and Roubaud has only encouraged me), footnotes appear ("Who footnotes a damn blog?", asks Rollo), though rarely as references, divisions into paragraphs often get tossed, and often an item beginning with topic alpha ends up on topic omega.

Sometimes, I set myself compositional tasks, or even games, sometimes of an oulipian nature, involving form or numbers or vocabulary or even punctuation. I've even written scatological limericks about centenarian composers. Now, I get more complaints about the writing style than about the content I don't mention, so I suppose I'm doing something right. The velocity and volume of posts to the blog has varied over time, slower in recent years due to all sorts of pressures on time (as well as a long period of not being able to use my right hand, which is tricky, being overly right-handed) but a less manic pace strikes me as just fine. It's still ancillary to composing, I have no idea how many people read it, I have no impression that it's helped my music get performed through the public-ness of it, but that's really beside the point: I continue to learn a lot, working through writing these texts, practicing composition in a textual medium that has yet to find its ideal forms, and still have plenty of fun with it.

Monday, March 03, 2014

Third Annual Festival of the Avant Garde

Shin-ichi Matsushita: Subject 17 |

The Third Annual Festival of the Avant Garde took place at 321 Divisadero St., San Francisco, in April 1965, sponsored by KPFA and run by myself, Peter Winkler and Robert Moran. Looking back on it I don't know how we had the guts: later endeavors have since convinced me of the enormity of such an undertaking. But we did, and it worked for the most part.

It was a sort of celebration of having the hall at all. KPFA and Ann Halprin’s Dancers’ Workshop joined the Tape Music Center in renting it. KPFA put on three concerts in the Festival, which was of course the first Third Annual. (There was a second one the following year, of which the less said the better.)

Earle Brown: Four Systems Robert Moran, piano; Georges Rey, violin; Gwendolyn Watson, cello

Robert Moran: Interiors Third Annual Ensemble

Peter Winkler: But a Rose John Thomas, countertenor; Peter and Judy Winkler, piano

Joshua Rifkin: Winter Piece Robert Moran, Georges Rey, Gwendolyn Watson

John Cage: The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs John Thomas; Peter Winkler

Ian Underwood: The God Box Nelson Green, horn.

Douglas Leedy: Quaderno Rossiniano for flute, clarinet, violin, cello, bassoon, piano, horn, cymbals and bass drum.

Third Annual Ensemble

Roman Haubenstock-Ramati: Decisions I Robert Moran; with prerecorded tape.

John Cage: three pieces for solo piano

Sylvano Bussotti: Piano Piece for David Tudor 3 Robert Moran

LaMonte Young: 42 for Henry Flynt Peter Winkler, gong

Shin-ichi Matsushita: Hexahedra Third Annual Ensemble

Morton Feldman: Durations 1 for piano, violin, and cello

Durations 3 for piano, violin, and tuba

Charles Shere: Two Pieces for two cellos

Ed Nylund, Gwendolyn Watson, cellos

Shinichi Matsushita: Hexahedra Third Annual Ensemble

Shere: Accompanied Vocal Exercises Linda Fulton, soprano; Peter Winkler, piano

Galen Schwab: Homage to Anestis Logothetis

Moran: Invention, Book I Robert Moran, piano

Anestis Logothetis: Centres

John Cage: Variations II Third Annual Ensemble

Third Annual Festival of the Avant Garde Ensemble:

John Thomas, voice; Nelson Green, horn; Arthur Schwab, Robert Moran, Ian Underwood and Peter Winkler, piano; Linda Fulton, soprano; Georges Rey and John Tenney, violin; Ed Nylund, Gwendolyn Watson, cello; Jim Basye, tuba; Charles Shere, bass drum and cymbals; William Maginnis, percussion; Judy Winkler, door and piano interior

I don't recall who played flute or bassoon in Quaderno, or who played piano and violin in the Feldman pieces. I do remember the hall was pretty well full for the opening concert, say 150 people. We scheduled the Soft Concert — so called because it was generally rather quiet — late, because a big Ernst Bloch memorial had been scheduled for that night in Marin county, and we knew a lot of our audience would be playing in it, so we scheduled the Soft Concert late, starting at 11 p.m. to give people a chance to get to 321 Divisadero. In the event, we had a full house.

Jim Basye had never played solo tuba before, it was his 16th birthday and the performance was gorgeous. The Japanese composer Shinichi Matsushita had never been heard in San Francisco before. 42 for Henry Flynt almost brought me and Bob Hughes to blows, in a disagreement which was finally healed later when he heard the piece again, a few years later, played just for him at a symposium at Esalen. Peter Winkler's performance at this Festival was much better, as can be heard online.

When I last wrote about the Festival, in 1975, I concluded with a Where Are They Now paragraph. Many are gone from this realm entirely, alas. All the composers were living when their music was programmed; of them Brown, Cage, Haubenstock-Ramati, Matsushita, Feldman, and Logothetis have left us, and I don't know about Galen Schwab, who seemed ephemeral even at the time.

Commonplace: the uses of history

Because of the bias of much new history against literate people with means, there has been a tendency to lose sight of sources that best preserve the voice of the past. As historical subjects, voiceless people without means have admittedly proven more amenable to confirming the truths about human nature that modern historians hold to be self-evident. But having means and being literate do not necessarily preclude ordinary experience or make one incapable of exemplifying ordinary life. By the sixteenth century it is certainly common to find literate people from good families whose lives are ordinary to the point of impoverishment. And unlike the voiceless masses whose human experience and culture they share, these people are also able to speak for their age. They explain as well as act. They not only have experiences typical of their time but do so self-consciously. They enable the historian to interpret the past with evidence from contemporaries. As a result historical study becomes a genuine dialogue between past and present.

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), p. xii

Friday, February 21, 2014

Ubu Roi in San Francisco

| Alfred Jarry: Ubu Roi translated from the French by Rob Melrose Directed by Yury Urnov The Cutting Ball Theater 277 Taylor Street, San Francisco; 415-292-4700 Extended to March 9, 2014 |

Lew writes that theater, to reassert itself in a time of declining attendance (which I'm not sure is true in San Francisco), should undertake the following "fixes":

•To attract a young, diverse audience, present work that’s reflective of a young, diverse audience.All of this is welcome comment, and much of it is being addressed in the San Francisco Bay Area. Last week we saw two plays whose theaters, productions, and acting seemed to me to address Lew's points. Perhaps the ticket prices did as well: I'm not too attentive to the prevailing costs of other kinds of entertainment. (On my fixed income, though, I must admit that our budget is strained by our theater attendance, running to a dozen or two plays in the course of a year.)

•Widen the perspectives being presented onstage.

•Place more faith in the artists.

•More funding for artists, less funding for buildings.

•Make the theater a more friendly and welcoming place.

•Make seeing theater easier on working parents.

•Lower the barrier of entry by lowering ticket prices.

I do have a problem, though, with one paragraph in his post — the one which presumably suggested the heading:

In truth theaters have a serious curatorial problem when it comes to choosing plays that a young, diverse audience can get behind. The fantastic documentary Miss Representation introduces the concept of symbolic annihilation in the media, and it applies exceedingly well to the theater. Why would young people (or people of color, or women) bother coming to the theater when they’re so rarely depicted onstage, and when they're so rarely in command of the artistic process? Is our dwindling audience truly a reflection of the educational landscape, or is it a reflection of a chronic homogeneity onstage exacerbated by an attendant homogeneity in our staffing?It seems to me this paragraph is predicated on the notion that one attends theater in order to verify one's own, or one's group's, existence. Surely one's existence is not in question, so this must stand for something else: a verification of one's relevance to one's context — social, historical, natural. I understand the contemporary anxieties that contribute to the generally felt need for this kind of verification, but I'm not sure I agree that theater companies have a curatorial responsibility to supply it.[His links]

I do think, pace Mike Lew, that "arts education" can address the problem of theatrical relevance: the problem is that we think of "education" as synonymous with "schooling"; that we've delegated education almost exclusively to the public and private schools. I often see parents with children in restaurants: these kids are being "taught" to attend restaurants, to observe social conventions concerned with dining in public, to appreciate diverse cuisines. I wish I more often saw children accompanying their parents in the theater.

It will be argued that the subtleties and references in the theater will elude them, that they won't "understand" the play. It's in the nature of childhood not to "understand"; children are used to it. I suspect they even enjoy it; I know I did: I still do. Theater is not boring or inaccessible because its literature is subtle, arcane, or referential. If it (or anything) is boring, that's the fault of an attendee who is demanding; if it (or anything) is inaccessible, that's because the means of access have not been provided.

Last week we saw two plays full of reference, both foreign, both complex, both with the added layer of difficulty that they depended, some of the time, on irony. I've already written (here) about Jerusalem, by the British playwright Jez Butterworth; the play and its production have increased in my appreciation since writing that post. (This often happens, and is one of the reasons I don't really like to be thought of as a "critic".) Let me tell you now about the second play we saw.

Over the years we've seen a number of productions of Alfred Jarry's absurdist masterpiece Ubu Roi. This is one of the best of them. The translation seemed to me to be very close, yet practical for American actors, audiences, and the stage. (I haven't re-read the play, either in French or English, for many years.) Yury Urnov's direction is inventive, consistent, always pressing forward though allowing frequent changes of pace and moments for the re-gathering of stage energy.

David Sinaiko is a marvelous Father Ubu: greedy and impetuous, childish and charming, vicious and hilarious. Ponder Goddard provides an opulent, intelligent Mother Ubu. It was she who nailed the play's references to Macbeth: one truly wants to see this pair in the Scottish Play, preferably in a similarly enterprising production.

The remaining cast — royalty, soldiers, crowds, armies, peasants, a bear, and so on — are ingeniously collapsed onto an ensemble of four: Marilet Martinez, Andrew P. Quick, Nathaniel Justiniano, and William Boynton, each and all of whom provide flashes of individuation, of articulation, of brilliance. The entire cast is completely engsging, and engaged in the play.

The function of theater, I've often thought, is to provide community — a shared understanding of shared experience in the human condition, subject to Nature, Society, History, not to mention Comedy and Romance. I think it's true that many of us make too Serious A Thing. One comment on my friend's Facebook link to Mike Lew's blogpost conveys a common response:

My pet peeve with "serious" movies, and somewhat with theater, is the makers' desire to be taken seriously, which is always fatal. I call it medicinal art — choke it down, it's good for you.Ubu Roi is "serious," but pretends to demand to be taken as pure satirical entertainment; I can't imagine anyone responding to it peevishly. Shakespeare, I think, would have loved it, and would have appreciated this production. I'd happily see it again.

Friday, February 14, 2014

Jerusalem

We'll have to read the play, my companion said later. I'm not so sure I'll bother. The play is laudable in its intent: to transfer the traditional English reverence for the powers of Nature to our own time, when paganism is no longer taken seriously except as it typifies antisocial behavior. Much of the time the play reminded me of Michael Tippet's opera Midsummer Marriage, of all things, and I even wondered if the playwright might perhaps be related to another British composer, George Butterworth (1885-1916), remembered primarily for his pastoral setting of Houseman's A Shropshire Lad. The pastoral tradition runs through the English sensibility from Chaucer on, and more than once this Butterworth, in Jerusalem, seems to be glancing sidelong toward As You Like It. But it is very much of our time, bringing town council enforcers out to the woods to lean on "Rooster" Byron, a middle-aged motorcycle acrobat hanging out in a house-trailer squatting on Council land in the woods.

Here he plays host to underaged girls, drifters, and assorted social misfits who hang about for free booze and pills, entertaining them with unlikely stories, linking himself to the English mythical and Romantic tradition. "What's an English forest for?", he asks pointedly, when it's pointed out he's harboring fugitive teen-agers.

As is so often the case, the relentless back and forth of dialogue and the constant narrative imperative of the play distract me from the playwright's real purpose, which is verifying the continued vigor and relevance of this pagan interplay of Man and Nature within the political and commercial corruptions of today's society. Apart from the vocal production, this performance has a lot to be said for it: a persuasive set, enterprising costuming, good blocking, detailed though not fussy stage direction.

The cast seemed to me to wrestle with Butterworth's demands, which are considerable. Brian Dykstra has a particularly difficult role in Rooster Byron, and manages it persuasively if not commandingly. The rest of the large cast fit in well; I was particularly taken with Richard Louis James as the Professor, Ian Scott McGregor as Ginger,, and Courtney Walsh as one of the enforcers, a small but telling part.

•Jez Butterworth: Jerusalem. San Francisco Playhouse , through March 8

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

Rusalka

|

|---|

| John William Waterhouse: Undine (1872) |

Misgivings first, to get them out of the way. Operas are written and generally produced to be seen and heard in a theater, the audience removed from the action. The voices, the expressions and gestures, the sets and costumes are designed to overcome the softening and "blossoming," you might say, that comes with distance. In the opera house the sound engulfs me. But in the movie theater it comes at me very clearly from loudspeakers front left and right. I see too clearly the mesh of the nets to which stage decor is attached. Closeups, no matter how beautiful the subject and how persuasive his expression, rob me of glances at the supporting actor standing just out of sight.

Still it must be said this Rusalka was beautifully and persuasively sung, acted, cast, and for the most part directed; and were surprised to hear the mistress of ceremonies, Susan Grant, seem to apologize for the physical production: we thought it remarkably apt.

One of my biggest complaints about these broadcasts-into-the-movie-theater is the treatment of the intermissions. Those interviews, well-meaning and "educational" as I suppose they are, intrude on my experience of the integrated work of art that is the opera. But it was amusing to watch the stage crew laboring at the complex and ambitious change of scene before the third act; and I was interested to hear the conductor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin (French-Canadian, bio here) talk about the opera with his youthful enthusiasm.

I thought the principals well cast and in good form: Renée Fleming in the title role; Piotr Beczala as the Prince; Dolora Zajick as the witch Ježibaba; John Relyea as the Water Gnome; Emily Magee as the Foreign Princess. The orchestra played well, with a good central European sound, I thought.

It's startling to consider that Rusalka is, technically, a twentieth-century opera, having been completed in 1901. There's no doubt about certain Wagnerian influences; you are reminded of the "Forest Murmurs" from Siegfried for example: more deliciously, Dvořák actually parodies Wagner from time to time — notably in the three ladies ho-jo-to-ho'ing about friskily at the opening. In the end, though, it's not Wagner but Janáček, of all people, who I think about on leaving the theater, Janáček of The Cunning Little Vixen.

This is not entirely because of the sound of the opera, of course: it's the opera in its entirety that does this. To me, this production of Rusalka is a totally integrated success: visual production, score, libretto and the performances merged into a serious and profound presentation of the water-nymph narrative — which is well worth contemplation.

THE MEME OF THE NAIAD goes back to prehistory, when everyone must have known the primal significance of water, without which life is impossible. Nothing more sacred than a spring — how many such mysterious, resonant, sacred places there must have been, articulating the wanderings of early nomadic humans, anchoring settlements as they began to appear.

And nothing more mysterious, I suppose, than the underground movement of water, rivers appearing out of nowhere and, occasionally, disappearing into the ground for no apparent reason, perhaps to re-emerge elsewhere. And, always, the vitality of the water, whether flowing animatedly or profoundly still yet somehow pregnant with sustenance.

And, mercurial and capricious, the waters can be dangerous and sinister as well as sustaining and nourishing. This is particularly true of the still forest pools, sometimes surprisingly, even unknowably deep, often with marshy edges, sometimes edged with treacherous quicksands. To this day there are sinkholes, filled with stagnant water, that are dreaded by the folks living nearby — I remember one we visited in the Var, in Provence, said to have been inhabited by a spirit who lived on the bodies of babies snatched from its edge.

On getting home from the opera Saturday I fetched down from the shelf a book I hadn't looked at in a number of years but remembered fondly, a child's edition, in English, of Undine, written in 1811 by the German Romantic novelist Friederich de la Motte Fouqué. (The edition I have is "retold" by Gertrude C. Schwebell, illustrated by Eros Keith, and was published by Simon and Schuster, New York, ISBN 9780671651602: I see there are a number of copies available inexpensively online, here for instance. Project Gutenberg has three earlier, less cut translations available for free download, and I'm glad to see scores of people have been getting them recently.)

Undine was set as an opera almost immediately on its appearance, by E.T.A. Hoffmann; thirty years later by Albert Lortzing; then quickly by the Russian composer Alexi Lvov (1846), followed by Tchaikovsky (1869). Nor was Dvořák's the last musical treatment: Hans Werner Henze composed music for a ballet with choreography by Frederick Ashton, first produced in 1958 by the Royal Ballet, with Margot Fonteyn in the title role. (The score was recorded in the 1990s with Oliver Knussen conducting; I'd like to hear it.) And I remember being fascinated by the inscrutably expressive sounds of Akira Miyoshi's radio opera on Ondine, composed in 1959, produced in Italy that year, winner of the Prix Italia in 1960, and issued on Time Records not long afterward.

Undine, to revert to the German spelling, is what seems to be called these days, often dismissively, a "fairy tale." The genre has dropped out of favor, replaced by science-fiction often set in a future, or "fantasy" set in some unspecified present. As it developed as folk literature, though, such tales performed an important function, I think. They are often cautionary, reminding the listener — not always a child, by the way — of the truth and certainty of proper forms of address humans should take toward Nature, toward essentials, toward limits on human ambition, social or individual.

In this particular story a knight-errant falls in love with the adopted daughter of a poor woodcutter and his wife. She turns out to be an Ondine, of course, a water-nymph, who miraculously appeared to the couple soon after the accidental and mysterious drowning of their own daughter. He takes her to his castle, ignoring his already arranged impending wedding to another (foreign) princess. Ondine, in assuming mortality in order to marry, guarantees the tragic outcome.

The rusalka is the Slavic form of the naiad; other forms are called, by their various communities, nixies, or sirens. The Italian willii are similar: the restless ghosts of women who have died of a broken heart, usually on the doorstep of the church when their groom has failed to turn up. From them, the expression: they give me the willies.

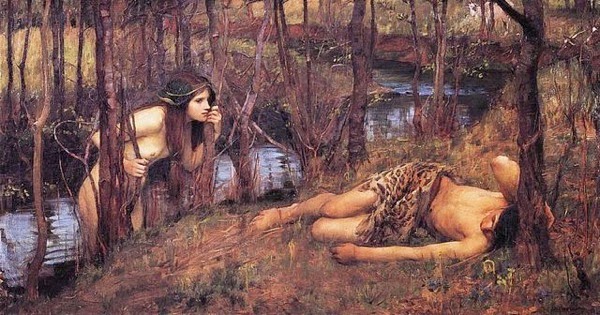

The Greeks were right, I think, to believe there were underground streams connecting, for example, the fountain of Arethusa in Sicily (at water's edge, in Siracusa), with an ultimate source somewhere in the Peloponnese. La Motte Fouqué's Undine travels easily between the pool of Dvořák's first act to the fountain of his second, presumably by swimming along one of these underground streams. The English painter John William Waterhouse, perhaps inspired (or cursed!) by his surname, painted at least two versions of a similar naiad, in similar settings.

|

|---|

| John William Waterhouse: A Naiad or Hylas with a Nymph (1893) |

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Four books of love and anger: Bang, Crane, Nesi

| •Herman Bang:Tina, translated from the Danish by Paul Christophersen (London and Dover N.H.: The Athlone Press, 1984, ISBN 0-485-11254-X) •Stephen Crane: Maggie: a girl of the streets; The Red badge of courage (in Stephen Crane: Prose and Poetry, The Library of America, 1984, ISBN 0-940450-17-8) •Edoardo Nesi: Story of my people, translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar (New York: Other Press, 2012, ISBN 978-159051354-9) |

Herman Bang (1857-1912), who wrote as a journalist and critic in the second half of the 19th century, was reasonably well known to his public but has been little read in English. (The Danish Wikipedia page presents him as an "author, journalist, columnist, essayist, stage director, presenter, lecturer and critic".) He published a half dozen novels, of which Tina (published as Tine in the original Danish in 1889) is the third. Claude Monet is said to have remarked that Tina, which he read in French translation, was an Impressionist novel, the best of any he knew, and the description is apt — if it makes you rethink just what constitutes Impressionism, who better to lead you to this than Monet?

Bang’s prose style is a little dry, lapidary, extraordinarily visual: you see virtually every hill, road, room, character in the novel. It is also incredibly frugal: the book is, in English, 174 pages long, though every corner of the events, the characters, the settings is fully presented, and you feel as if you’d lived through these tumultuous days and their deceptively tranquil context with every nerve.

The central character, whose name is the novel’s title, is young, modest, intelligent; an observer; a young woman, preoccupied with her aging parents, aware of and to an extent intrigued by the greater world beyond her rural village, a schoolteacher immersed in the sleepy village life. There’s something Ibsenish about her, but she is not angry or sullen: one of Bang’s gifts is his sympathetic portrayal of what others might turn into tragedy as, instead, simple resigned reality.

For me, beyond the events and the characters, it is the social distribution within the village that the author particularly illuminates. Almost every layer of class is presented, sympathetically, as occupying position beyond any question of fairness or egalitarianism. No one is resentful; each person has a role, a position. Bang’s presentation of the justice and the social practicality of this distribution is touching and tender, and if his characterization, in measured accounts of conversation and of internal thought, made me think of Henry James, his depiction of Tina and others of her class brought Gertrude Stein’s Three lives to mind.

The English translation, by Paul Christophersen, seems to have been made at least thirty years ago, and is hard to find. The original Danish is available as a free download from Project Gutenberg, and a quick glance at it suggests the translation is reasonably accurate but presented to quite a different effect, the original laconic short sentences and paragraphs formed into a more conventional narrative style. Even so, this slender novel was a perfect pendant to the recently read I Promessi Sposi, and is likely to prove as memorable.

TINA TOOK ME NEXT to a re-reading of Stephen Crane (1871-1900), who I haven't looked at in sixty years or so. Something I read somewhere suggested the battle descriptions in the Danish novel resonated with those in Crane's masterpiece, and I can see the point, but it's misleading. The two authors have completely different agendas, as different as their national mentalities. Contemporaries, they were both prodigies; they both worked in journalism, fiction, and poetry; and they both developed styles that stood between naturalism and an arresting sort of objective lyricism.

Crane, in fact, is thought to have inspired such Objectivist poets as William Carlos Williams, a fellow New Jerseyite, as well as such novelists as Ernest Hemingway; Herman Bang's poetic style makes me think more of the quieter phenomenalism of, say, Francis Ponge. Why is this? It is the difference between a European (and particularly a cisalpine european) mentality and an American one: the European is more noncommittal and readier to look back toward historical precedent; the American is more urgently expressive and inventive. Tina may make me think of Three Lives, but in style and method it reaches back to Jane Austen; Crane looks forward toward Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway.

Another thing: Bang was born into a village mentality; Crane quite definitely into a city one. Rural Denmark in the 1860s, war or no war, was a very different situation than urban New Jersey-New York in the 1870s. The difference between the authors is represented by the difference between their heroines: Tina is quietly competent, thoughtful, relatively secure in her self-awareness; Maggie is insecure, reactive, apparently inept. If they come to the same end, they arrive at it for very different social reasons.

Maggie doesn't read nearly as well as Tina today, in my opinion, but it's a fascinating look into the formative period of Crane's career, recording the dialect and slang of the Lower East Side of the 1890s and probing the effect of poverty and other social insecurities on the lives of his characters — who are otherwise not introduced nearly as sympathetically or in such detail as you'll find in Tina.The Red Badge of Courage, though, holds up quite well. Crane writes like a poet as often as he does like a novelist; his sentence structure and vocabulary are often studied and shaped; his physical descriptions are often arresting, if perhaps a bit mannered:

In the eastern sky there was a yellow patch like a rug laid for the feet of the coming sun; and against it, black and patternlike, loomed the gigantic figure of the colonel on a gigantic horse.and, famously,

The moon had been lighted and hung in a treetop.

The white-topped wagons strained and stumbled in their exertions like fat sheep.

The red sun was pasted in the sky like a wafer.Much of the time Crane's hero is portrayed in interior monologue though seen objectively, from an observant narrator's viewpoint:

It seemed to the youth that he saw everything. Each blade of the green grass was bold and clear. He thought that he was aware of every change in the thin, transparent vapor that floated idly in sheets… And the men of the regiment, with their starting eyes and sweating faces, running madly, or falling, as if thrown headlong, to queer, heaped-up corpses — all were comprehended.The book is justly celebrated as the great Civil War novel, and to my mind it has the requirement of every great war novel: it portrays the absurdity, the injustice, the uselessness of war — and the possibility that it can be fascinating. While its horrors are evident among fallen soldiers, its effect on civilian life are rarely present — another contrast with Tina. Nor does Crane look at political or social history, the causes and consequences of war or that particular war. He is concerned with its impact on his maturing central figure.

EDOARDO NESI IS AN Italian novelist, born in 1964 into a well-to-do industrial family, owners and operators of textile mills in Prato. His entry in the Italian Wikipedia lists eleven titles he has published, beginning in 1995, but Story of my people is the only one I have seen. (It appeared as Storia della mia gente. La rabbia e l'amore della mia vita da industriale di provincia (Milano: Bompiani Overlook, 2010) and immediately won the significant Strega Prize.)

The book is part memoir, part socioeconomic criticism, for Italy's textile industry fell victim to globalization in the early years of this century, and in 2004 Nesi sold the family industry, founded by his grandfather and great-uncle in the 1920s. He was never really an industrialist himself; he always wanted to write; he was drawn to literature and to American culture; but he'd stepped into the direction of the firm — Lanificio T.O. Nesi & Figli S.p.A. — when it became his generation's turn, sharing it with his cousin Alvaro.

Story of my people easily and efficiently gives all this background, the facts set out clearly and objectively, and the context too: the great Italian art-and-industry of textile design and weaving, whose history reaches back centuries. The implications of Nesi's book, however, go much further. Between the lines the reader intuits the social justice and meaning of artisanal, family-owned, community-minded industry and commerce. The loss of the "values," the world really, associated and expressed by such an economy — necessarily local, however distant its sources and customers — is poignant, probably even tragic.

This justifies and explains the subtitle of the Italian edition: Anger and love in my life as provincial industrialist. Nesi's writing is understated, colloquial, reasonable. It reminds me of the style of a curiously similar book, Gianfranco Baruchello's How to imagine: a narrative on art and agriculture, (New York: McPherson & Co., 1983), co-written with the American Henry Martin. Baruchello, a painter and conceptualist influenced by Marcel Duchamp, turned to what you might call agricultural conceptualism on the outskirts of Rome in 1973, as How to Imagine and later Why Duchamp explains. There's something about the folksy, clear, patient, reasoning, yet principled and even partisan writing in both Baruchello and Nesi that I find immensely persuasive.

But Baruchello withdraws from the decadent and probably soon failing context of avant-garde art in the 1970s to find solace in local sustainability, guerrilla though its action may be; and Nesi has turned from Story of my people to political engagement, elected last year to the Chamber of Deputies as a representative of Tuscany.

Why, apart from the curiosities of their surnames, have I grouped Bang, Crane, and Nesi? The three books have a tenderly regretful note in common, a regret born of the fault they find with their socio-historical milieu — anger, muted or implied, at the failure of their time to pursue the humanitarian values they once loved. Some may suggest that nostalgia is the common thread, but I don't think so. I have to believe that the function of these books, of their authors' writing, is to get the reader to thinking about the aspects of human social living that have been eroding, and the possibility of returning many of them to viability even in the greatly more dense and complex world we have created for ourselves. The material of Crane's books represents the cataclysmic moment between past and future; we will certainly have to endure such cataclysms on our way to a more sustainable life on earth — if in fact it is not already too late, as I have just read at The Nation.

Monday, January 13, 2014

Einstein on the Beach

The Chatelet production of the Wilson-Glass opera Einstein on the Beach can be seen in its entirety — four and a half hours — streaming on line:

Many thanks to Daniel Wolf for bringing this to my attention.

Saturday, January 11, 2014

Manzoni: I Promessi sposi

| Alessandro Manzoni: I Promessi sposi, translated as The Betrothed by Bruce Penman. Penquin Books, 1986. | |||

|

What a book! On the first level simply a long, somewhat rambling historical novel about Milan and its surroundings in the seventeenth century, written two hundred years later, the book — virtually Manzoni’s only extended prose work — admirably integrates historical scholarship, personal observation of character and place, and political philosophy.

The “promised spouses” (the Italian formula for “affianced”) of the title, Renzo and Lucia, are peasants living in a village on Lake Como, near Lecco. Their marriage is prevented by one of the local nobles who has his own designs on Lucia. After a failed attempt to circumvent that, the couple separate: Renzo goes to Milan, is caught up in bread riots resulting from poverty and drought, and escapes to his cousin in Bergamo; Lucia takes refuge in a convent, is abducted…

But enough of plot: I do hope you’ll read the novel, and part of its interest of course is in the suspense. Only a small part, though: those reading the book as a romantic historical novel about a pair of lovers may lose patience with what I think is its true subject-matter, and its intricate interest and importance.

Manzoni begins with a foreword it would be wrong to skip, opening in flowery archaic language purportedly quoting an ancient author:

History may truly be defined as a famous War against Time; for she doth take from him the Years that he had made Prisoner, or rather utterly slain, and doth call them back into Life, and pass them i Review, and set them again in Order of Battle.After a page of this sort of stuff, set in italics, the author lays down his ancient text and speaks for himself, noting that History too often loses sight of the ordinary men and women who lived through the eras historians deign to consider. He notes, too, the turgid style of the original, alternating between lofty rhetoric and crude dialect. He gives up reading the thing, but quickly thinks

“Why not take the sequence of fact contained in this manuscript,” I thought, “and merely alter the language?” There were no logical objections to this idea, and I decided to follow it. And that is the origin of this present work, explained with a simplicity to match the importance of the book itself.So immediately Manzoni’s book takes up a number of contexts:

• it was written in 1820-1825 about events of 1620-1630, nearly two centuries earlier (and I read it in 2013, nearly two centuries later)

• It attempts to re-introduce the common man into a context generally restricted to elevated historical figures

• it attends to appropriate language and style

And underneath these evident and acknowledged contexts there is another agenda, not particularly well hidden. The book’s action takes place in a politically eventful moment, when Milan and its duchy are controlled by Spain; Bergamo is part of the Venetian Republic; Austria is threatening from the north and northeast; and France has designs on Monferrato in neighboring Piemonte. Furthermore, the action involves the closing years of the long wars between Catholics and Protestants. And, most importantly, the close of the feudal era when lawlessness and exploitation was an accepted aspect of daily life, and the poor but generally honest and respectable contadini and villager was at the mercy of the rich, powerful “nobleman” in his castle on the hill, and his band of thugs and stooges — the “bravos” who do his dirty work.

I was drawn into the book first by Manzoni’s marvelous description of its physical setting, the mountains and riverbanks to the south and east of Lecco, country not that different from terrain I’ve spent weeks walking in, fifty or a hundred miles to the west., A poor man, Renzo walks when he must go from Lecco to Milan, from Milan to Bergamo. The parish priest rides a mule; ladies are carried in litters; noblemen ride coaches. In every case the tempo is quite different from ours in the 21st century, and climate, physical nature, and observation of the faces and characters of those one meets are taken more slowly, more contemplatively, and therefore more objectively, at a pace giving time to correct immediate impression, prejudice, and habit.br>'

The book should be read at a similar pace, I think; and should be considered while reading and afterward, letting the book bloom in the mind, responding to our time and its own, as a good wine is allowed to bloom in the glass and the mouth, and afterward in sensual memory.

The characters in the novel are memorable and attractive, even the villains — stock characters, all of them (young lovers, parish priest and his housekeeper, Cardinal, ruffians, evil nobles), but individuated through description and dialogue. The settings are evoked sometimes through meticulous description, sometimes arresting observation — the Milan cathedral, for example, seen from miles away, at a time when the city was still contained within its walls.

The historical events are exciting and resonant: war, famine, plague, all recounted with both mesmerizing immediacy and resonance that inescapably suggests World War II, the Balkan wars, today’s events in Africa and the Middle East.

And then there’s the language. Manzoni published the novel in 1827, but within a dozen years revised it out of its original dialect of Italian into the Tuscan dialect centered on Florence — thereby cementing that dialect as standard contemporary Italian. The revision seems to involve mostly simply substitutions of vocabulary, with a few additions or clarifications of text, and virtually no cutting.

I haven't yet found what exactly the dialect of the original version is called: it's not Piemontino, though it shares with that dialect certain leanings toward French. "Equal," for example, is eguale in the first version, uguale in the revision. I know this because I found a fascinating edition of the novel online, a facsimile (not e-text or digitized text) of an edition (Milano: Domenico Briola, 1888) of the revised version, with the original text inserted in smaller size between the lines.

Years ago I bought a fine copy of an old edition of I Promessi sposi, and it turns out to have an interesting history of its own. It was published at Firenze in 1845 by Felice Le Monnier, who based the text on the 1832 edition by David Passigli e soc.. Le Monnier was noted for his contempt for author's rights, and merely pirated the Passigli edition, heedless of Manzoni's subsequent revision into the definitive text. Manzoni sued and was eventually awarded a substantial award. I don't know how large the 1845 edition was, or how the copy I have came to whatever used-book store I bought it in — though a recent New Yorker article on such matters does give me some pause.

I read Penman's translation with both the Le Monnier and the interlinear edition at hand, comparing often enough to get the distinct impression that this is a fine translation, idiomatic in English, respectful to the original style, and faithful to the text.

Some have characterized the book as a romantic epic, along the lines of Tolstoy's War and Peace — a book I'm embarrassed to say I haven't (yet) read. It would be wrong, though, and perhaps disappointing, to think of it as primarily a narrative about the betrothed Renzo and Lucia: instead, it is — as another reader suggested the other day — an epic, a narrative description of the general state of the soul of a nation. I'm hard pressed to think of another prose example, and I wonder if Manzoni weren't channelling such older epics as Aeneid or Chanson de Roland or Orlando furioso. Whatever, I Promessi sposi is essentially Italian; it speaks from an honest and good heart; it is ample, intelligent, poetic, philosophical, evocative, good-humored, and inventive, and I consider it one of the greatest novels I have ever read.

Tuesday, January 07, 2014

More

Next day's play, back home:

TONY

Also from Cuba, this menu: tuna, pork paté, bean soup…

(Zulu nods.)

…corn — take four ears, Dane.

DANE

Nope. Don't like that junk.

TONY

Don't like corn? What, can't give corn room? Take tuna, then. Four cans.

FINN

Open four cans, chop kale — don't cook them, mind! Let's take them over…

ZULU (chanting)

They stay here, fast with fury, lean with love,

Afar from Goa's sand they ever rove

With foul lung, shut eyes, blue lips, mean claw,

None sees that emir, king, even that shah

Iran sent with pale hope, with fair thin face,

Part hope, part fear, part sent well high, part base.

Even them boys that Cuba sent feel well

Upon fast part from Goa's inky Hell.

TONY

Poet! Well come here, Zulu! Let's clap, gang,

Fair rime, that foul pros ever said they sang.

DANE (hops with FINN: slow jive time)

Uggh. Stop, Finn, lest your toes turn down with mine… look away, boys… drop, fast, when Zulu says that oboe ends…

TONY

What oboe, Dane? They hear dogs bark, with keen ears, ever pert. What oboe tune hear thou, fine zany Dane? What wood wind sang from over that long vale?

DANE (fury with TONY)

When they take bird meat, song will stop fast. Keep back!

(Fast fade)

Monday, January 06, 2014

News from Lumaire

For a few months, since returning from France last July, I've been toying with the idea of publishing his series of translations of short narratives written in French by the elusive Jean Coqt, apparently a Franco-American who settled in Grenoble or its environs sometime after the end of World War II — perhaps a veteran of that war; I'm not sure.

(One of the attractions of the Coqt-Lumaire project in fact is the obscurity of Coqt, whose improbable surname raises suspicion that he may be nothing more than an invention of the almost equally elusive Lumaire.)

I enjoyed conversation with Lumaire, a slightly goofy, complacent fellow, perhaps sixty years old, a bachelor who lives with his nervous, intelligent white poodle. I can't explain the affinity I felt for him: we have nothing in common beyond our first names and our fondness for the writing of Gertrude Stein.

We spent a couple of hours over a glass of wine in a pleasant little sandwich-shop in Eugene, and he sent me off with a sample of his own writing — apparently excerpted from an adventure yarn he's working at, called, tentatively, Near Peru.

It's very different from the two installments he's given me of his Coqt translation, which I hope to publish either here or elsewhere in this new year.

Should we take Lumaire's writing seriously? Dunno. It makes me think of Abish, though he reaches, more likely, toward the Mathews model. In any case, here he goes:

"ONCE," TONY SAID, "nine guys flew back from Cuba; then they were here: Scot, Dane, Finn, five wops, Zulu.

"They knew hope; they knew fear more. They said many fell. Wops have seen many fall: snow, rain, sand, bogs."

Alps were hard ― sere, Scot said. Finn took more time with that:

"Were Alps ever hard! Most boys find home flat, calm, snug. Alps seem like Mars."

Dark Zulu, brow knit, fell into rage.

"Puny guys! Girl!" (Howl.)

"Look here: when Girl naps, boys swim away, fast. Then lope back home over sand." Eyes shut, Zulu adds: "Also, wops stay back with girl."

"Let's stop over here." Tony said. "When they come with boys, we'll bark like dogs. What goes with tuna?"

"Buns," Dane said. "Warm herb teas," Finn adds.

"Thin been soop," said Zulu.

(That calm, cool, easy frog Jean Coqt isn't with them, lest the next day's pale moon fade dead away.)

. . . .

Look, Finn! What evil gale wind blew that foul ship upon that hard dark rock? Warn Tony! Fast! Yell, Finn!

Tony sees. "Haul away, Zulu! Hard port! Left, fool! Left side, hard! Haul away!"

. . . .

Whew. What next?

Day's work over, cold moon rose over pale blue seas. Soft wind blew: then, dead calm. Zulu naps. Won't wops wake with waxy wine, when warm? Wink, Jean Coqt, thou cold, cool, cozy frog! They need your calm mind here!

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

André Lurton, vignoble

by André Lurton with Gilles Berdin

ISBN 978-2-35639-039-4

Bordeaux : Elytis, c2010.

“ANDRÉ LURTON, born 1924, is a French winemaker and winery owner,” states the English-language Wikipedia. Curiously there seems to be no page for him at French-language Wikipedia, and this little book, nicely edited from seven conversations between Lurton and the French wine journalist Gilles Berdin (b. 1962), indicates that there certainly should be.

Before turning to Lurton himself, a few words on Berdin’s intentions are in order. This is one of a series of eleven such books introducing significant personalities in the world of French winemaking to their audience. (So far only one has appeared in English: Conversations Over a Bottle With Denis Dubourdieu.) Berdin describes his intent:

“These conversations, which are not biographies, result from the observation that there are extraordinary people in our landscape of French wine; a most diverse, amazing, exciting group: the owners, winemakers, cellar masters, and tasters. It seemed urgent to collect their words, especially if, as some fear, the vignoble is increasingly passing into the hands of what we call “les institutionnels: " banks, insurance companies, multinationals, investment companies.

I want all these enthusiasts to share their passion and experience, and transmit some of their memory to future generations: their knowledge, their skills, their emotions ...

As the charm of conversation lies in its imperfections, digressions, repetitions, silences, contradictions, onomatopoeia, paradoxes, laughter ... I'll open their words as is, without settling, aeration or dressing them up in a decanter. ”

(My translation.)

So the book, while short, is charmingly discursive. It does have a logical structure, though, basically chronological; and it begins, notwithstanding Berdin’s apology, with a bit of biography.

Lurton’s mother, née Denise Recapet, died in 1934 when Lurton was only nine years old. His father, who worked for a British commercial group, never remarried, and it was his mother’s parents who were apparently most influential in the boy’s upbringing. The grandfather, Léonce Recapet (1858-1943), must have been an imposing presence in the boy’s life. Léonce took up his own father’s distilling business after his four years of military service — he must have seen the Franco-Prussian War — and built it into a considerable success; then went on into the wine industry, buying his own Château Bonnet in 1897, later adding other properties.

Lurton saw service himself, of course, during World War II and the German occupation; some of the most moving pages in this book describe the difficulty of those days, and then of the actual battle he saw after the return of the Free French, when he fought the retreating Germans in eastern France.

The first fifty pages bring us from these biographical accounts — scanty but suggestive of the influences that molded the man — to the years after demobilization, lean years of returning to normal. The grandfather was gone, and he worked alongside his father until an uncle helped him take own his place in the vignoble, at Château Bonnet. He learned to be not only a vineyardist but a farmer as well, raising corn and potatoes, providing for a young family, as he’d married shortly after the war.

Succeeding conversations provide insight into the Bordeaux vinification methods as they slowly evolved in the years after the war, from relatively haphazard production to much more carefully calculated techniques. There are marvelous pages on the complex regulations concerning real estate, appellations controllées acreages, and financing: French readers will follow these pages more closely, but we Americans find here hints at the baroque intricacies of the French bureaucratic mind, which trains the French to master subtlety and patience.

Lurton discusses degustation, the tasting of wine; its vocabulary; its variability from one expert to the next. He discusses screw-caps, which he favors for white wines. He discusses the problems of press reviews. There are a couple of delicious pages on the subject of Robert Parker, the American writer whose ratings have so greatly influenced the production and marketing of wine in its international market. Berdin asks if Lurton thinks Parker has truly influenced methods of wine-production:

Lurton: Oh yes! Everybody wanted to make Parker’s wine. Where it had the most influence, though, was on the techniques of sampling. (He laughs.) … Each time he comes [to the vignoble], a couple of weeks or a month before there’s a tripotage in the cellars to prepare the samples. There’s a visit to this cave, that barrique… he knows about it, but there’s nothing he can do.

Lurton has things to say about regulation: he has little patience for the labeling laws, or for the current concern for safety and security in general. “The media are partly responsible for this propensity to fear everything.” And then there are his observations of journalists: “I’ve rarely met an informed or an objective journalist… it’s extraordinary how inept they can be, what stupidities and errors they can write… there are many who know nothing at all about a probem and who want to try to discuss it.”

Lurton emerges as an opinionated, hands-on veteran of the long and fascinating transition from the last decades of traditional winemaking, through the interruption of World War II, through the emergence of scholarly and theoretical approaches to the art, through the political and corporate domination of its industrialization, always with a pragmatic and, it must be said, often surprisingly patient long view of his metier.

He’s unhappy with the world as he finds it now, globalized and regulated by bureaucrats; but then what reasonable man over sixty is not. “France is a unique country which can do fantastic things,” he summarizes, on the closing page, “but which always criticizes itself, destroying itself. That’s what worries me for my children and grandchildren. But I hope they’ve had a minimum of training not to go too far wrong and to dare to act, to have some dynamism…

"A rich laborer, feeling his death coming on, gathered his children together, and said to them…”

[He laughs…] “Work; take pains; that’s the approach that misses least!” (Travaillez, prenez de la peine: c'est le fonds qui manque le moins! )

Ultimately these conversations over a bottle with André Lurton suggest the possibility there will always be a few wise old men (and women too), who have known hunger and hard work, who aren't fooled by fashion; and that that's enough to get humanity through a rough patch and back to basics. I'll lift a glass to that!

Saturday, December 07, 2013

Einstein, Poincaré, and the drift toward Relativity

Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time. By Peter Galison. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2003.

MOM ALWAYS LISTENED to a radio program on weekday mornings — some kind of news commentary, I think it was. It came on at nine o'clock sharp, and always began with the stentorious announcement that "It's High Noon In New York." Hearing that, I'd always look at our clock, which would read something between 8:45 and a few minutes past nine. It always fascinated me, this difference in times. I knew that anything said on the radio must be true, especially if it came from far away, yet my brain told me that it was nine o'clock, though our clock was rarely so sure.

Local time, Daylight Savings Time, Standard Time. Growing up in the country even a kid was aware of all these things, with that dim awareness kids have of such things. Except for school days, time was measured by sun and stomach: but school required promptness, and you wouldn't want to get there too early but you couldn't be late, and it was, oh, a good forty-minute walk.

These uncertainties prevailed even among urban adults until well into the 19th century. In spite of its title, chosen I think more for merchandising than for accuracy, Peter Galison's book is about the history of the synchonization of clocks in the Western World — as that history affected the gradual emergence of Einstein's theory of relativity, it is true. A photograph in this sometimes maddening book shows the Tower of the Island, in Geneva, which about 1880 had three prominent clocks indicating the time(s): 10:13 here in Geneva, 9:58 in Paris; 10:18 in Bern. Six years later two of the clocks had been taken down, as time was now sychornized all the way from Paris to Bern, and beyond.

The problem, of course, is that the earth rotates on its axis (which is on the whole a very good thing). I look up at noon: the sun's as high as it will climb today, though probably in the southern sky. In New York, though, that happened three hours ago.

There were a number of reasons the 19th century wanted to standardize time and synchronize clocks. It was a logical concomitant of the Industrial Revolution, of the Enlightenment. And therefore its history is grounded in that of England and France. Galison's hero, in this book, is certainly Henri Poincaré (1854-1912), the French polymath, graduate of the École Polytechnique, that quintessentially French institution born of the Revolution.

One forgets the essentially Rational nature of the Revolution, which replaced the superstition- and religion-obsessed Monarchy (which was positioned on the Great Chain of Being, leading between the lowest worm and God, just below God Himself) with a Republic grounded in the principles of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. One of the major points was to replace arbitrary verities emanating from divine revelation or regal whim with equally arbitrary verities determined by groups of scientist-philosophers. The Metric System, for example, was developed by the Polytechnique, for the practtical reason of facilitating trade throughout the nation through standared weights and measures: a bolt of cloth woven in Nîmes should be measured the same as one woven in, say, Paris.

(Another factor: the importance of bringing every corner of the nation under the administration of a central authority in Paris. The history of local-versus-capital tension is long, complex, and fascinating.)

Galison's story is significant and absorbing, but his editors and publisher have not done him many favors. There are odd lapses in grammar and even odd errors — in one case, for example, a confusion of starting and ending positions in an account of signaling between positions. The book is rich with detail, ranging from Poincaré's forensic investigation of a coal-mine explosion to the survey of meridians in Africa and the Andes. The poltics of scientific research would be a rich enough subject for a history all its own, and Galison valiantly brings it in, as well as the comic-opera argument between England and France over the decimalization of time measurement (France lost) and their joint research into the precise distance between the Greenwich meridian and that of Paris (England seems to have yielded).

Galison's study is a chapter in the history of ideas, and a measure of the difficulty of writing such a chapter is itself a central aspect of his book. Early on, he describes the nature of this complexity, calling it "critical opalescence." He is so fond of the metaphor, and the reader needs so much to keep it in mind, that it's worth a long quote to show his method:

Imagine an ocean covered by a confined atmosphere of water vapor. When this world is hot enough, the water evaporates; when the vapor cools, it condenses and rains down into the ocean. But if the pressure and heat are such that, as the water expands, the vapor is compressed, eventually the liquid and gas approach the same density. As that critical point nears, something quite extraordinary occurs. Water and vapor no longer remain stable; instead, all through this world, pockets of liquid and vapor begin to flash back and forth between the two phases, from vapor to liquid, from liquid to vapor—from tiny clusters of molecules to volumes nearly the size of the planet. At this critical point, light of different wavelengths begins reflecting off drops of different sizes—purple off smaller drops, red off larger ones. Soon, light is bouncing off at every possible wavelength. Every color of the visible spectrum is reflected as if from mother-of-pearl. Such wildly fluctuating phase changes reflect light with what is known as critical opalescence.

This is the metaphor we need for coordinated time. Once in a great while a scientific-technological shift occurs that cannot be understood in the cleanly separated domains of technology, science, or philosophy. The coordination of time in the half-century following 1860 simply does not sublime in a slow, even-paced process from the technological field upward into the more rarified realms of science and philosophy. Nor did ideas of time synchronization originate in a pure realm of thought and then condense into the objects and actions of machines and factories. In its fluctuations back and forth between the abstract and the concrete, in its variegated scales, time coordination emerges in the volatile phase changes of critical opalescence.

(Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps, pp. 39-40)

Galison's discussion traces the development of time standardization and coordination through a fascinating period, the century-plus leading from the French Revolution (1789) to the publication of Einstein's first papers on time and space — in the history of ideas, from the disastrous triumph of Rationalism to the cubist fragmentation of Relativity; from the displacement of divine and regal authority by that of republican committees to the eventual triumph (or disaster) of unbridled democratic individualism and the provisional, negotiable structures that follow.

The only hope for truth or certainty, given the "critical opalescence" of the philosophical, political, and even scientific landmarks along this historical path, lies in some kind of reasoned abstraction defining an intellectual framework within which to negotiate the numbers assignable to the objects we contemplate: time, distance, justice, value, administration. It's too much to hope for a clear presentation of this problem, let alone a clear discussion of the concepts and illuminations brought to the party by such minds as Poincaré and Einstein — and a number of others mentioned in passing in Galison's book.

I wish he'd had better copy editing. I wish someone had asked him to resolve repetitions, to clarify arguments, to provide timelines. I wish the index were more detailed. But I thank him for giving us a book worth setting next to Ken Alder's The Measure of All Things, and for including copious notes and drawings and photos and an extensive bibliography. Written toward a popular audience, it's a book worth keeping and ruminating over.

Tuesday, December 03, 2013

Remembering Judy Rodgers

Judy was the age of our oldest daughter, and she lived a couple of years with her; she came young to "our" restaurant; she lived in our house one summer while we were away; she traveled a few weeks with us another summer, when we took lodgings together for a couple of hot weeks in Firenze.