I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED

I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED eccentric violin concertos, by which I mean those somehow standing aside from the standard repertory. Mozart's, of course; and the Sinfonia Concertante.

Harold in Italy. The neglected ones by Schumann, Dvorák, Goldmark, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Lou Harrison; the familiar but still fascinating ones by Sibelius and Berg. In many of these concerti, it seems to me, the soloist stands somewhat apart from the orchestra, the composer's (and the performer's!) strategy for dealing with the differences between the collaborators in terms of dynamic and tonal range and, especially, potential weight. One doesn't like to attribute too much "meaning" to music, but it's hard to escape the thought that the soloist-orchestra dynamic recalls that between Self and Society, or — better, in my opinion, and certainly more representative of my own attitude — Self and Nature.

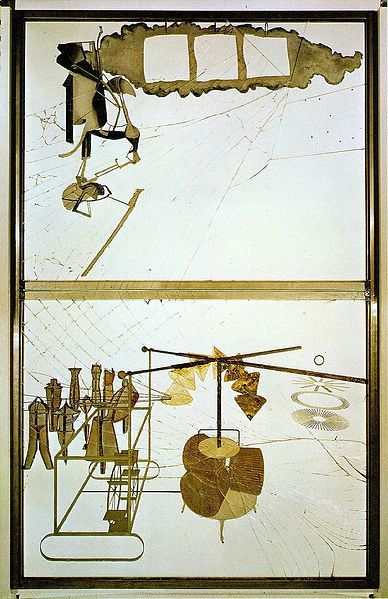

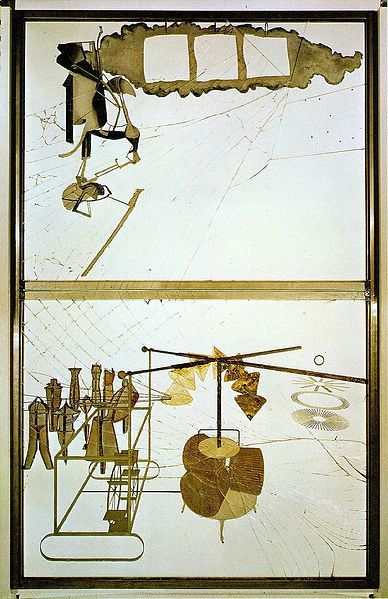

From the middle 1960s forward for about twenty years I was absorbed in an operatic "version" of Marcel Duchamp's great painting

La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même. The painting, on two sheets of glass, measures about nine feet high by nearly six feet wide, was begun in 1913, and was abandoned ten years later. (It's currently at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where, the last time I saw it, many years ago, it seemed to need a fair amount of restoration. Several replicas have been made, and are in collections of museums in Tokyo, London, and Stockholm.)

Marcel Duchamp: La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même |

Duchamp preceded the actual laying-out of the painting, on its sheets of glass, with fairly elaborate verbal notes and drawings. The most elusive of these was a full-size drawing done in pencil, as I recall, on the plaster wall of an apartment he was living in in Paris in 1912 or so; it has disappeared. Others, though, on various scraps of paper, were carefully retained, and have been published in several editions. Of these perhaps the most important was the

Green Box,translated in 1957 by George Hamilton and published three years later in an elegant small-format edition which I bought at the time and began making my own notes in, setting various pages to music. (I've written about all this in a lecture,

How I Saw Duchamp, available as a booklet from

Frog Peak.)

I was fascinated by

La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même for the same reason that years before I had been fascinated by James Joyce's marvelous last novel

Finnegans Wake, currently in the news thanks to a fine first-person reader's account by Michael Chabon,

published in

The New York Review of Books. Both of these masterpieces of Twentieth-century Modernism took their authors years to produce, and were even before their undertaking themselves products of further decades of what you might call internal preparation, in terms of contemplation of the position of man (and Artist) in the context of that epochal time.

And both

La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même and

Finnegans Wake have grown, since their creation, considerably beyond even

that, incorporating huge amounts of critical commentary and subsequent work (in many media) by artists they have influenced. It's as if they — and other similar masterworks — were originally the product of some kind of fertile, prolific mycorrhizal organism. Or, to consider a less alarming, inorganic analogy, as if they were regional testimony to very extensive geological formations, only occasionally becoming visible through such surface evidence as hills and valleys, watercourses, presence of characteristic vegetation.

Man Ray: Dust Breeding |

The Nazca plain |

(Indeed, Man Ray's photograph of a section of Duchamp's painting,

Dust Breeding, treats

La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même as precisely that sort of phenomenon: the glass, onto which Duchamp had been gluing lead wires outlining the Chariot region of the work, had been stored flat under his bed, gathering dust; the resulting photo suggests an aerial photograph of the

Nazca Lines in the Peruvian desert.)

MUCH OF MY CONCERTO was composed in Europe: we used to spend a month or two there in alternate summers, taking leaves of absence from our jobs, sometimes touring by car or rail, on other vacations renting a house for a few weeks, or house-sitting when we got the chance. In the late 1970s we spent a couple of weeks on the Ile d'Arz, in the Gulf of Morbihan, near the alignments of Carnac, and there I spent a lot of time thinking about the center section of the opera I was writing to Duchamp's painting. At the center of the opera would be a long ballet, with some singing, which would in some way "depict," or at least somehow comment on, the actual workings of

La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même, as Duchamp described (or at least considered) those workings in the notes published in the Green Box.

At the back of my mind, too, was Alban Berg's wonderfully eccentric

Chamber Concerto for piano, violin, and thirteen wind instruments. I knew I wanted the dancers in this ballet to move among musical instruments. Two wind quartets and two string quartets would be on stage; also the piano. The lower half of Duchamp's painting — the "Bachelor Region," with its prominent central "Chocolate Grinder" — was probably the inspiration for my imaginary mise-en-scène; the Grinder suggested the piano.

Above, the painting represents the "Bride Region," with the Bride's "Halo" along the top, surrounding its three empty squares, and the "Hanging female thing" at the left. The lowest part of this

Pendu femelle irresistably suggested a violin bow: very well: a violinist would be somehow levitating downstage center above the piano and its surrounding accompanying quartets, the rest of the orchestra in its pit between stage and audience.

Bride: violin; Bachelors: wind instruments; Grinder: piano.

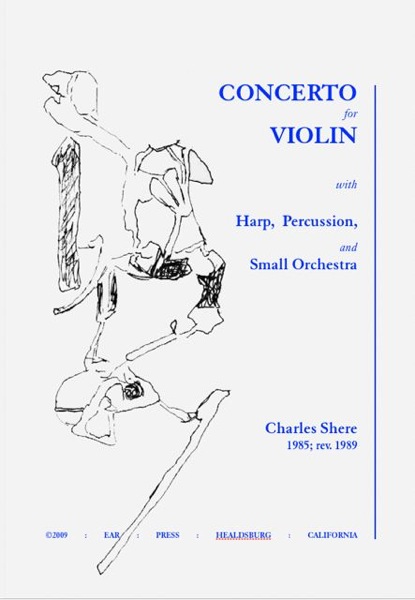

The two concertos would be interleaved, movement by movement, only occasionally superimposed. A fair amount of the music was sketched that summer on the Ile d'Arz and elsewhere, and in 1985 I extracted the violin concerto component from the opera score so that it could be performed separately. Unfortunately, the first movement of the violin concerto, which depended heavily on two wind quartets whose music was notated graphically, resisted all my attempts at a conventionally notated realization, so it is omitted from the stand-alone version, and the second movement has been broken into two sections to provide the conventional three movements of the concerto form. (Perhaps one day I'll solve that notational problem.)

(As for the Piano Concerto, it has yet to be extracted from the opera score. The solo music for the piano has been, however: it's available as the

Sonata: Bachelor Machine, completed in 1989; one movement of the piece can be seen, performed by the estimable

Eliane Lust,

here.)

In 1987, I think it was, the Cabrillo Music Festival approached me asking about any not-quite-finished orchestral pieces I might have, and I mentioned the Violin Concerto. Fine, they said, they'd like to see it. I handed it in, as it then stood, not quite filled out, and the original first movement still missing. After a few weeks I heard that they were intrigued by its "spareness," and that they wanted to give it a concert reading on a program devoted to new pieces perhaps not yet quite finished.

I had heard the San Francisco violinist

Beni Shinohara, who had been playing chamber music with Eliane, and had been greatly impressed with her musicianship, tone, and intellectual curiosity. She agreed to take the project on, and somehow persuaded a friend, the pianist-conductor Joan Nagano, to help, by improvising a condensation of the orchestral accompaniment for solo piano, thereby extending the concerto's mycorrhizal network into a sonata for violin and piano — which I have neither seen nor heard.

The Cabrillo connection suggested a little joke to me, and I incorporated the snare drum part from Lou Harrison's

Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra into my own score. Lou was a fixture at the Cabrillo Festival; I admired him and his

Koncerto, as he preferred to call it; and it had itself been inspired by Alban Berg's violin concerto. So I lifted the snare drum part, exactly as it sounds in his concerto, at the original tempo and loudness and pacing. (This of course required my completely re-notating and thus considerably complicating Lou's original "spelling" of the music.)

Beni played beautifully, and it didn't hurt that she looked splendid, too. Much of the actual concert was a mess, with inept conducting and inadequately prepared orchestral parts, not to mention uninteresting composition. Daniel Carriaga referred to all this in his review in the Los Angeles Times:

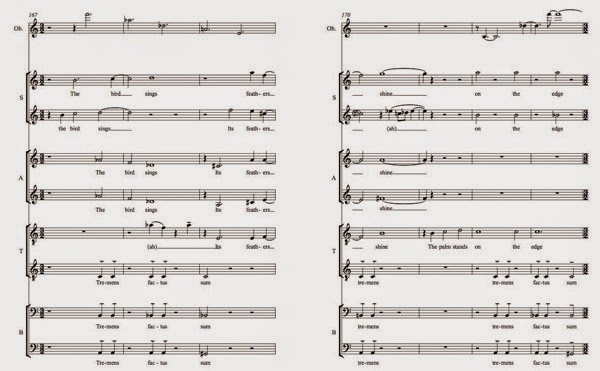

…Saturday afternoon, five works from the California Composers Project were unveiled by the Festival Orchestra.

The players' patience was sorely tried with this event. Only Charles Shere's spare but gloomy Concerto for Violin and Harp, Percussion and Small Orchestra (1985) deserved such a showcase.

Shere's brooding and intense concerto, an essay in small, telling musical gestures, occupies its 15 minutes engagingly. It was performed sensitively by violinist Beni Shinohara, solidly accompanied by the orchestra led by Ken Harrison.

Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1990 (retrieved July 7, 2012)

For my concerto, though, the violist and assistant conductor Ken Harrison had accepted full responsibility, had learned the score perfectly, and conducted gracefully and effectively. The orchestra, too, seemed intrigued and appreciative. I remember the first trombonist, for example, thanking me for writing for

alto trombone, an instrument far too neglected. (Its solo injections, i.e. at m. 35 in the second movement, owe something to Ravel's

Bolero, to continue the thread of musical cross-pollination.)

After the performance Beni asked me what the piece was about. I'd refrained from any such discussion while she was preparing it, but was willing enough to hint at things now. The violin is Duchamp's "sex-wasp," I told her. I was a little embarrassed: well, it’s about the Bride being ready, and the Bachelors never quite engaging. I thought it was something like that, she said. (Beni's husband Katsuto is a respected urologist, who some years later, coincidentally, I was to meet in a professional capacity.)

I ran into Lou, too, who seemed intrigued by the piece, and I confessed I'd stolen the snare drum from his

Koncerto. "Better you'd have lifted the violin part," he replied.

I wish I could share with you the recording made from the radio broadcast of the concert. The piece has not been performed since its premiere — all too often such premieres are in fact

dernieres as well. I've finally got around to publishing the score, though, and you can now buy it

online, and perhaps, if you're very clever, synthesize another performance — or even convince another orchestra to schedule it. I'll supply the orchestral parts!

IF YOU'VE VISITED this blog before you're no doubt aware of my long-running infatuation with La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même, the chef-d'oeuvre Marcel Duchamp abandoned in 1923, which has since attained the status of legend within the annals of Modernism. He had worked on it for ten or twelve years; I worked on it longer, ultimately to an even greater degree of futility.

IF YOU'VE VISITED this blog before you're no doubt aware of my long-running infatuation with La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même, the chef-d'oeuvre Marcel Duchamp abandoned in 1923, which has since attained the status of legend within the annals of Modernism. He had worked on it for ten or twelve years; I worked on it longer, ultimately to an even greater degree of futility. I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED eccentric violin concertos, by which I mean those somehow standing aside from the standard repertory. Mozart's, of course; and the Sinfonia Concertante. Harold in Italy. The neglected ones by Schumann, Dvorák, Goldmark, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Lou Harrison; the familiar but still fascinating ones by Sibelius and Berg. In many of these concerti, it seems to me, the soloist stands somewhat apart from the orchestra, the composer's (and the performer's!) strategy for dealing with the differences between the collaborators in terms of dynamic and tonal range and, especially, potential weight. One doesn't like to attribute too much "meaning" to music, but it's hard to escape the thought that the soloist-orchestra dynamic recalls that between Self and Society, or — better, in my opinion, and certainly more representative of my own attitude — Self and Nature.

I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED eccentric violin concertos, by which I mean those somehow standing aside from the standard repertory. Mozart's, of course; and the Sinfonia Concertante. Harold in Italy. The neglected ones by Schumann, Dvorák, Goldmark, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Lou Harrison; the familiar but still fascinating ones by Sibelius and Berg. In many of these concerti, it seems to me, the soloist stands somewhat apart from the orchestra, the composer's (and the performer's!) strategy for dealing with the differences between the collaborators in terms of dynamic and tonal range and, especially, potential weight. One doesn't like to attribute too much "meaning" to music, but it's hard to escape the thought that the soloist-orchestra dynamic recalls that between Self and Society, or — better, in my opinion, and certainly more representative of my own attitude — Self and Nature.