| •Legends of the Bay Area: Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Marin Museum of Contemporary Art 500 Palm Drive, Novato, California tel. 415-506—0137 W-F 11-4; Sa-Su 11-5; closes April 5 |

| •Mildred Howard: Spirit and Matter. Richmond Art Center 2540 Barrett Avenue, Richmond, California tel. 510-620-6772 Tu-Sa 10-5; Su 12-5; closes May 24 |

I knew that he painted, but always assumed that his painting amounted to something of a hobby. Hobby: terrible word. The French have a better expression, violon d'Ingres , referring to the music Ingres turned to when he wasn't concentrating on his primary art, painting and drawing. It's not uncommon for artists to work at two quite dissimilar genres, often one of them time-based — music, theater, poetry — and the other primarily visual: painting, sculpture.

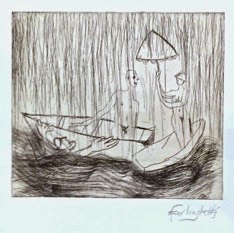

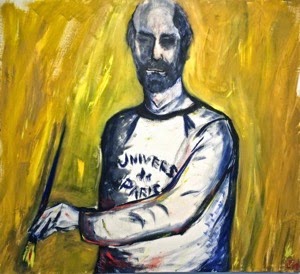

The exhibition of Ferlinghetti's visual work, primarily painting but including also a few prints, suggests that he often confronts his work quite seriously, though he's quoted as saying "Painting is more like play than work." He began painting in Paris in the late 1940s, when he was studying literature at the Sorbonne, and has maintained a studio ever since coming to San Francisco sixty-odd years ago. (He is still painting, at 96.) The earliest work in this exhibition, Deux , recalls Cocteau; though a canvas, it's essentially a line drawing of two profiled male faces confronting one another, one upside-down, like the figures at the corner of a playing card.

Though he admired the abstract expressionism of the Beats, he found himself unable to resist representation, especially of the figure. (He dislikes the term "abstract expressionism," finding it a contradiction in terms.) His best paintings bear the scrubbed light of Ab Ex painters: Elmer Bischoff and Hassel Smith come to mind. The calligraphy of the framing inside the hull of the boat in Provincetown makes me think of Franz Kline, whose influence shows up elsewhere. But, staying with Provincetown , the two figures inside the hull again recall school-of-Paris painters; it's not a stretch to relate them back to the profiled faces in Deux.

The boat is a recurring motif in Ferlinghetti's painting; perhaps a memory of his own transatlantic crossing.

|  |

| Sun Boat 2 (2009) |

In Sun Boat 2 the boat is little more than counterweight to the brilliant energy of the upper half of the canvas; in an untitled print (made at Crown Point Press in San Francisco) it forms part of a narrative, in a small piece whose elegance and wit is hard to resist. (The male figure reaching up out of the water will remind some of us of both Picasso and Picabia, but the piece is fully Ferlinghetti's.)

A number of the works here make comments of a social or political nature, and they seem to me the weakest work — rushed, blatant, obvious; more slogan than painting — though the 1999 Mother Russia , whose expressive face is defined with an artfully drawn hammer-and-sickle, and whose posture and tone recall the Russian qualities of Chagall and (Arshile) Gorky, is exceptional in this respect, quiet yet rather deep, "poetic" in its juxtaposition of signs (woman, bird), telling it the downward motion of the street.

A number of the works here make comments of a social or political nature, and they seem to me the weakest work — rushed, blatant, obvious; more slogan than painting — though the 1999 Mother Russia , whose expressive face is defined with an artfully drawn hammer-and-sickle, and whose posture and tone recall the Russian qualities of Chagall and (Arshile) Gorky, is exceptional in this respect, quiet yet rather deep, "poetic" in its juxtaposition of signs (woman, bird), telling it the downward motion of the street.At 96, Ferlinghetti is free from anxieties concerning position; his painting, like his poetry, stands on its own, a good member of a rich and vibrant society of artists, poets, writers, activists. This is a retrospective in more ways than one: the viewer can't help recalling the work of previous decades, can't help noting the inevitable vitiation of their movements, platforms, and insights. Yet the human spirit persists, and expression is the inevitable result. To Ferlinghetti's credit there's a fair amount of joy and beauty as well as occasional impatience with the social human condition.

The Painter (1989) |  |

Installation, Mildred Howard: Spirit and Matter , Richmond Art Center

MILDRED HOWARD is an artist of considerable standing in an area — Northern California — not exactly hurting for powerful, mature artists. She has worked in collage, painting, assemblage, and sculpture for decades, always bringing to her work intellectual energy drawn from a sober, serious contemplation of self and society. I don't know any artist who excels her in treating the significance of being African-American in contemporary American society, or in treating the history of that situation, without bogging down in mere politics-of-the-moment. A "white," I can't of course speak from within that "situation": but it does seem to me the significance, the meaning, the roots and the reach of Howard's work must be the same to a black viewer as to a white.

It's curious: her work is intensely personal, sometimes using her own face and hand as the visual center of the work; yet the result transcends self. That wonderful critic R.H. Blyth writes, in his Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics , of four types of expression: from top to bottom, as you might say, "the object treated objectively", "the object treated subjectively," "the subject treated objectively," "the subject treated subjectively." (His examples range from "almost all of Chaucer; Shakespeare's songs…" at the top to the "Chamber of Horrors" at the bottom: "The larger part of Byron, a great deal of Shelley and Keats… the pièce de résistance is Yeats' Had I the heaven's embroidered cloths/… Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.)

In this formula Mildred Howard often works, I think, with the subject the "black" presence in the American scheme) treated objectively. I have generally preferred objective objects, and this is why I like Puryear and Guston; but if you're going to make a career as an artist contemplating the significance latent in the intersection of self and society, you can't do that any more objectively than Howard does. She never complains or shouts or cajoles. She contemplates, as I say, and presents the material of her contemplation, and expresses its complexity and reality — its objectivity — as a matter of social fact.

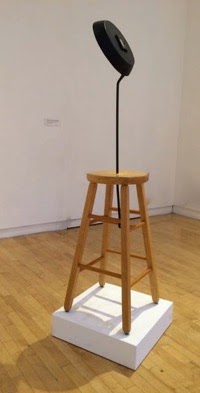

She also contemplates Art. One of the best pieces here, I think, and one of the best pieces of its type I've seen anywhere, is a tall four-legged unpainted wooden stool out of whose seat has risen a long-handled cast iron skillet. Skillet to the Frying Pan: Sitting Black , it's called — Howard's titles, often small poems themselves, are never to be neglected; they lead the viewer's mind into unspecified richnesses associated with the visual "meaning" of the pieces they name.

She also contemplates Art. One of the best pieces here, I think, and one of the best pieces of its type I've seen anywhere, is a tall four-legged unpainted wooden stool out of whose seat has risen a long-handled cast iron skillet. Skillet to the Frying Pan: Sitting Black , it's called — Howard's titles, often small poems themselves, are never to be neglected; they lead the viewer's mind into unspecified richnesses associated with the visual "meaning" of the pieces they name.The visual reference includes Duchamp, of course; if like me you live with a copy of his famous Bicycle Wheel you'll greet Sitting Black with familiar pleasure. But at the center of the bottom of this skillet, angled up toward you as you lean in to look at it, is an old-time photographic portrait of an African-American woman, unnamed, unknown most likely unless a member of the artist's own family. Suddenly the gap, the gulf between everything Duchamp was concerned with and the history of the African-American presence in American society hits you like, well, a black iron frying pan.

Resonance; resonance. Yet the sculpture — and sculpture it is, there's no denying that — is beautiful, elegant, and aloof in its elegant beauty. If its size and proportions suggest a standing figure, it's a figure Joan Mirò might have conjured, with Giacometti somewhere in his mind. Howard treats this object of her own devising subjectively, to judge by the title, but she's reaching toward objectivity, and her work — her skill, patience, sophistication, and above all intelligence — permits us to follow her in completely resolving the subjective component to achieve a fully objective state of mind, contemplating the object without an agenda, without straining at a specific (let alone a socially charged) meaning.

Howard has been well known for a series of pieces referring to House; two are present here. In the installation photo you can see one playing domesticity and edge: the empty geometry of the house is made of channels of aluminum, I believe, completely covered on every surface with table knives. The floor is littered with an amazing collection of silver — candlesticks, compotes, candy-dishes, trays, pitchers — ultimately forming a path leaving the house toward the gallery wall, covered with white wallboard into which dozens of knives — sharp knives, not tableware — have apparently been stabbed, perhaps thrown, in gestures which can be interpreted as either violently aggressive or merely — merely ! — futile and frustrated. It's a big, complex, finally irresolute piece, I think: objectively subjective, perhaps.

In an adjacent hallway there's a small example of Howard's bottle houses, cabins made almost exclusively of bottles. This one is small, made of dozens of identical brown glass bottles each holding only an ounce or two of… I don't know what, originally: the label mentions beer, but these look more like vanilla-extract bottles. Whatever they are, they are of course as beautiful as glass: perfectly uniform in color and texture and size, with the inert regularity of manufactured components — brick, tile. Lean into the open end of this bottle house and admire the light it admits.

In an adjacent hallway there's a small example of Howard's bottle houses, cabins made almost exclusively of bottles. This one is small, made of dozens of identical brown glass bottles each holding only an ounce or two of… I don't know what, originally: the label mentions beer, but these look more like vanilla-extract bottles. Whatever they are, they are of course as beautiful as glass: perfectly uniform in color and texture and size, with the inert regularity of manufactured components — brick, tile. Lean into the open end of this bottle house and admire the light it admits.This is a big show, a very important one; a mid-career retrospective presenting an artist who has quietly staked out for herself an uncommonly intelligent, probing, thoughtful position on art, self, and society, and expressed that position with unusually prolific, clear, consistently elegant, and often joyous work. I looked at this show thinking of great Richmond Art Center shows of the past, of Tom Marioni's direction in the 1960s, for example. Everyone involved with the show, its installation, and its curation is to be congratulated.

NO VISIT TO THE Richmond Art Center should overlook the marvelous folk sculpture tucked away, almost unnoticeably, in the shrubbery of the courtyard. They make a particularly poignant counterpoise to Mildred Howard's retrospective. I'm embarrassed and ashamed that I don't know who made them, and it's late Saturday night, I can't call to find out before putting up this blog Sunday morning — I'll try to rectify this in a later correction.

There's one other piece of sculpture in that courtyard, and I'm really unhappy about its treatment. It's a beautiful, formal, abstractly geometrical work in marble by the Italian-American San Francisco sculptor Elio Benvenuto. I knew him, casually, back in the 1950s I think: a tall, slender, elegant, courtly man with a fine eye and hand, a true heir to the Italian sculptural tradition.

There's one other piece of sculpture in that courtyard, and I'm really unhappy about its treatment. It's a beautiful, formal, abstractly geometrical work in marble by the Italian-American San Francisco sculptor Elio Benvenuto. I knew him, casually, back in the 1950s I think: a tall, slender, elegant, courtly man with a fine eye and hand, a true heir to the Italian sculptural tradition.This piece should be indoors, on a stand lifting it well off the floor, where the viewer can take his time with it, on its terms, letting light play across its polished surfaces, bounce off its edges and details. Instead it's on the ground on raw dirt, in shadow, at the edge of a concrete pavement, for all the world as if has been rejected, abandoned with no thought at all to its beauty, let alone the skill and dedication of the artist who made it.

Come to think of it, Benvenuto's position, seventy years ago, as an Italian immigrant bringing the artistic values of his society to the San Francisco Bay Area, is somewhat analogous to Mildred Howard's. And to that of the temporarily anonymous maker of the charming yet poignant cement sculptures nearby. An exhibition presenting work by the three artists together would be a fascinating depiction and examination of the urges and preoccupations they hold in common.

Keith Haring (1958–1990)

Keith Haring (1958–1990) Plate (opposing rabbits), ca. 1010–1130

Plate (opposing rabbits), ca. 1010–1130

Vessel (ring-tailed cat), ca. 1010–1130

Vessel (ring-tailed cat), ca. 1010–1130

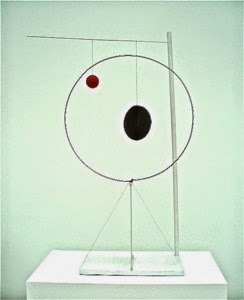

You see three of the earliest pieces in the photo above, with the fascinating Object with Red Ball (1931) at the center. This photo, from a different

You see three of the earliest pieces in the photo above, with the fascinating Object with Red Ball (1931) at the center. This photo, from a different

TWO YEARS AGO or so I wrote briefly

TWO YEARS AGO or so I wrote briefly

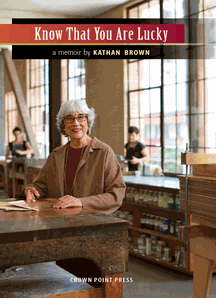

THIS IS AN IMPRESSIVE book, and I don't say that merely because it has forced me to rethink a number of opinions I've held for a number of years — though that alone is something of an accomplishment.

THIS IS AN IMPRESSIVE book, and I don't say that merely because it has forced me to rethink a number of opinions I've held for a number of years — though that alone is something of an accomplishment.

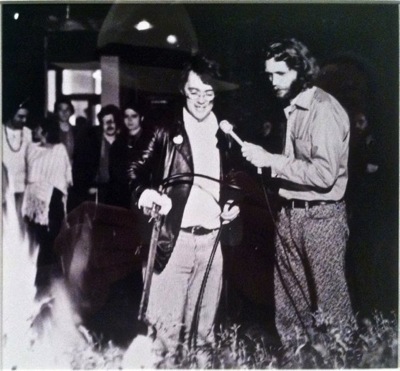

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this?

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this? Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.

Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.