•Virgil Thomson: Music Chronicles 1940-1954.

The Library of America, 2014

ISBN 978-1-59853-309-5

Edited and with notes and chronology by Tim Page

|

Eastside Road, December 4, 2014—

I HAVE SPENT the last two or three days reading through Virgil Thomson, having received the surprise gift of his

Music Chronicles from the publisher; I’m not quite sure why. Perhaps in the hope that I would write about the book here.

I’ve written about Virgil here before, of course. [

Here and

here.] We met him in the middle 1960s, and it’s bemusing to think that I’m now a generation older than he was when Lou Harrison brought him up our front stairs, at 1947 Francisco Street, to introduce us over lunch.

I never knew him well, though Lindsey and I visited him in his Chelsea Hotel apartment whenever we went to New York, back in the 1970s and ‘80s. He invited us to dinner there once or twice; we dined out once or twice; we dined at Chez Panisse once or twice. He was friendly to us; conversation was by no means one-sided. He gave me some advice on vocal writing, and I was bold enough to dedicate my Duchamp opera to him; he seemed genuinely interested in it.

During the fifteen years or so that I wrote music criticism professionally, for the Oakland

Tribune, I dipped into his published criticism fairly often. I always wrote better, I think, for having read him, though it was sometimes necessary to resist his influence: one must speak, after all, with one’s own voice.

What a pleasure, now, to re-read Thomson! His prose style is so direct, clear, engaged and engaging, occasionally surprising; and the ideas he considers and reveals with that style are so persuasive, well-grounded, and important in considering his subject-matter — which is always, in the published work, music, the art, its producers, and those aspects of society (including history and economics) which are inextricably connected with it.

Music Chronicles reprints the four volumes of newspaper columns Thomson issued during his career and, I think, in one case at least, after his retirement from the New York

Herald Tribune, which had the intelligence (and forbearance) to sustain him from October 1940 until October 1954:

The Musical Scene;

The Art of Judging Music;

Music Right and Left;

Music Reviewed. There are also 25 articles and reviews from the NYHT that Thomson had not chosen for republication, a couple of essays specifically about the mechanics of newspaper music criticism, and a welcome collection of eight early articles are reviews from before his NYHT stint. Missing are , among other things, the articles Thomson wrote for

The New York Review of Books. Perhaps they’re being saved for a second volume in this quasi-official Library of America publication (the nearest thing our country has to Frances Pleiade Edition).

What I’ve been reading, then, is essentially the New York Herald Tribune, from late 1940 to about 1948, as it confronted, through its chief music critic, a musical scene incredibly rich in any epoch let alone wartime. “Chief” music critic, for Thomson had a stable of stringers only too happy to pick up a little pocket money covering events even Thomson didn’t have time for: John Cage, Lou Harrison, Peggy Glanville-Hicks and others. (Their writing was often nearly as impressive, and nearly always greatly influenced by their boss’s.)

These are basically concert reviews and Sunday “think pieces,” as we used to call the more extended essays we wrote on generalized subjects or aspects of music other than its actual performance. I don’t know how VT actually wrote his copy, whether at home or in the office, from notes or not, in revised drafts or not. I like to think he wrote as I used to, at his desk, on the (manual) typewriter, on long sheets of foolscap, triple-spaced and pasted, eventually, end to end, lest the sheets get out of order on their way to the linotype machine. Revisions, if any, would have been made in heavy pencil between the lines.

As you read through these pages you quickly form the notion there was little revising to be done. VT seems usually to have the nut of his essay in mind before beginning to type it; the nut and a few of the sentences as well, especially the opener. Headings, too, sound like his voice: “Age without Honor”, “Velvet Paws”, “Being Odious” (a comparison of three orchestras), “Hokum and Schmalz”, “Free Love, Socialism, and Why Girls Leave Home” (a review of Gustave Charpentier’s opera Louise).

VT writes about complex matters, subtle distinctions, hidden influences, unsuspected associations, dealing with an art form notoriously resistant to verbal analysis and discussion. He is successful largely for four reasons, I think: keen observation, clear analysis, economical expression, great assurance. Let me give one example, from a review of a Philharmonic Orchestra concert that had presented Mendelssohn’s

Midsummer Night’s Dream, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, and Darius Milhaud’s

Suite française and

Le Bal martiniquais:

There is humanity in the very texture of Milhaud’s writing. Tunes and countertunes and chords and percussive accents jostle one another with such friendliness, such tolerance, and such ease that the whole comes to represent what almost anybody might mean by a democratic way of life. Popular gaiety does not prevent the utterance of noble sentiments, and the presence of noble sentiments puts no damper at all on popular gaieties. The scenes have air in them and many different kinds of light, every brightness and every transparency, and no gloom or heaviness at all.

You might complain that this description, while perfectly apt, will only seem so to those who know Milhaud’s music and who therefore already have this impression. VT does not merely preach to the choir, though, in his graceful, informed, yet often plainly vernacular prose; he voices realizations not perhaps otherwise verbalized, sets the music almost visually and certainly intellectually in front of an audience that otherwise confronts it only with the ears.

(Or program notes; or an invisible announcer’s introductions: these come in for careful, thoughtful, and critical assessment from time to time.)

VT writes about judgment, modernism, pipe-organ voicing, the choice of repertory, the effect of audience or the lack of audience, the divisions of labor among “executants,” managers, boards of directors, educators, and critics. He writes about technical matters like rubato, dynamics including crescendo, the choice of tempo, and intonation, making such things understandable, I think, by the lay public. He describes the rhythmic differences between tango, rhumba, beguine, and Lindy hop. He writes about generalized complex historical matters, and he writes about personalities.

I despair of describing VT’s writing, when it is so easy simply to give quotations, so here they are, more or less at random:

Stravinsky knocked us all over when we first heard him, because he had invented a new rhythmic notation, and we all thought we could use it. We cannot. It is the notation of the jerks that muscles give to escape the grip of taut nerves. It has nothing to do with blood flow… —Music Chronicles, p. 969

The Satie musical aesthetic is the only twentieth-century musical aesthetic in the Western world. Schoenberg and his school are Romantics; and their twelve-tone syntax, however intriguing one may find it intellectually is the purest Romantic chromaticism. —ibid., p. 126

Oscar Levant’s Piano Concerto is a rather fine piece of music. Or rather it contains fine pieces of music. Its pieces ae better than its whole, which is jerky, because the music neither moves along nor stands still. The themes are good, and if they are harmonically and orchestrally overdressed, they are ostentatiously enough so that no one need suspect their author of naïveté.—ibid., p. 139

The greatness of the great interpreters is only in small part due to any peculiar intensity of their musical feelings. It is far more a product of intellectual thoroughness, of an insatiable curiosity to know what any given group of notes means, should mean, or can mean in terms of sheer sound… the great interpreters are those who, whether they are capable or not of penetrating a work’s whole musical substance, are impelled by inner necessity to give sharpness, precision, definition to the shape of each separate phrase.—ibid., p. 275

Impelled by inner necessity to give sharpness, precision, definition to the shape of each separate phrase. This is what VT does, thoroughly and reliably, day after day and week after week, in prose which never fails to suggest conversation, discussion among similarly thoughtful (if perhaps never quite so articulate!) participants.

A couple of times, while typing the above quotations, Gertrude Stein came to mind. VT learned the rhythms of his prose, and beyond the rhythms the phrasing, I think, from his long experience with both her conversation and her prose. One of her most significant lectures was called “Composition as Explanation,” and I think its title (let alone its substance) offers a key to what VT intends in his journalism: he composes his explanations in an earnest desire to share and celebrate meaning: the meaning of music, of art, of humanity.

Let none of the above mislead you: VT has pronounced dissenting opinions from time to time, and delights in expressing them. In his first NYHT review he dismissed Sibelius’s Second Symphony as “vulgar, self-indulgent, and provincial beyond all description” (this from a critic proud of his Kansas City background). He doesn’t much like Brahms. As for Beethoven, he writes, in an essay discussing Mozart’s liberal humanism,

Mozart was not, like Wagner, a political revolutionary. Nor was he, like Beethoven, an old fraud who just talked about human rights and dignity but who was really an irascible, intolerant, and scheming careerist, who allows himself the liberty, when he felt like it, of being unjust toward the poor, lickspittle toward the rich, dishonest in business, unjust and unforgiving toward the members of his own family.—ibid., p. 80

He is writing about Beethoven the man in that passage, of course, not about Beethoven's music. He has extremely insightful comments on the music. He sees the problem of the Fifth Symphony, for example, and of the Ninth. I think he understands the causes and the meaning of the German sensibility in music; that's revealed in a remarkable aside finding

parti pris between the (otherwise very different) musical sensibilities of Chopin and Schumann. But over and over in these pages VT praises French sensibility and distrusts German. He notes, somewhere, that Beethoven introduced a note of militancy into concert music that has continued in the German musical tradition up to the middle of the 20th century; a note utterly lacking in the French repertory. He links this introduction to the difference between the German beat-oriented impetus and the French one, dependent on the phrase.

The American musical establishment favored the German wing of the history almost from the start and continuing, certainly, down to our own time. My own grandfather, hearing of my dedication to music when I was in high school, counseled me to learn German to prepare for study abroad and to be able to learn from the “important” sources. Beethoven continues to dominate repertory, though his symphonies seem finally to be giving room to those of Shostakovich, which (as VT points out) are hardly less militant.

Of course VT was an expatriate living in France from the end of his college years until 1940, his formative years. He had gone to Paris, not Berlin, to study with Nadia Boulanger; he’d remained there to converse with Stein, to observe Satie, to read Rameau, to refine an essentially Parnassian taste. His detractors, whether confronting his musical composition or his journalism, found him waspish, simple, trivial, or stilted, in order to marginalize his work as gossipy, dull, irrelevant, or pretentious, and thereby avoid having to give serious thought to the implications of his findings.

But I think his detractors were (and are) wrong. Wrong, and small themselves, and p[perhaps fearful of foundational truths about their own work. Music is primarily an intuitive thing, it is true, but it supports intellectual consideration carefully and authoritatively brought to it. That, ultimately, is VT’s achievement, that and the entertainment he provides in the process.

Music Chronicles contains, besides VT’s work, a fine, full, helpful Chronology of his life, the customary note on the text sources, concise but useful page-notes, and a near-encyclopedic section (85 closely-set pages!) introducing the many musicians referred to, whether a Bunk Johnson or a Pierre Boulez. The volume is exceeding well thought-out, nicely designed, easy on the eyes; and deserves a place close to hand.

A CORNER OF THE BLEAK Gatchina Palace, outside St. Petersburg, as painted earlier this year by the California artist Inez Storer. And this is just a corner of the painting, too — or, rather, a detail taken from nearly the center of the painting, the entirety of which I'll set at the end of this post.

A CORNER OF THE BLEAK Gatchina Palace, outside St. Petersburg, as painted earlier this year by the California artist Inez Storer. And this is just a corner of the painting, too — or, rather, a detail taken from nearly the center of the painting, the entirety of which I'll set at the end of this post.

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this?

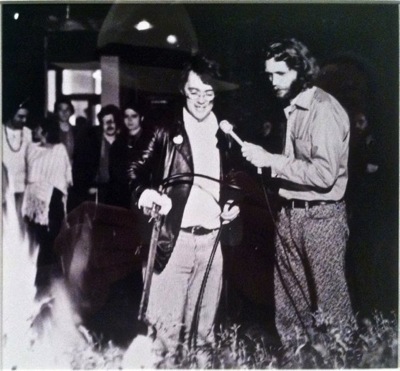

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this? Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.

Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.