THIS IS AN IMPRESSIVE book, and I don't say that merely because it has forced me to rethink a number of opinions I've held for a number of years — though that alone is something of an accomplishment.

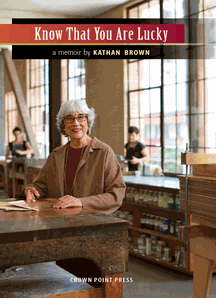

THIS IS AN IMPRESSIVE book, and I don't say that merely because it has forced me to rethink a number of opinions I've held for a number of years — though that alone is something of an accomplishment.Kathan Brown is the founder of Crown Point Press, the San Francisco press that has for fifty years now been printing and publishing etchings, engravings, aquatints, photogravure, woodcuts, and occasionally monotypes by some — perhaps most —- of the most significant artists working during that period, ranging from Wayne Thiebaud and Richard Diebenkorn to John Cage and Sol Le Witt.

She is also an accomplished writer. In 1976 she published her first book, Voyage to the Cities of the Dawn, a strangely moving, evocative meditation, through words and photographs, on time and perception, suggested by a trip she had taken to ancient sites in Yucatan and Central America. A number of titles followed that related more directly to various of the artists and the methods occupying her attention at the press: of those titles I know only the ones relating to John Cage.

In 2004, though, she published The North Pole, perhaps a companion to Voyage to the Cities of the Dawn: a description, with copious photographic illustration, of a voyage she took across the Arctic Ocean on an icebreaker. And now she has given us Know That You Are Lucky, her memoir of the years at Crown Point Press; of the method and mantra, you might say, of printmaking; of the exceptional men and women with whom she has worked.

In a little over three hundred pages, divided into twenty chapters, Know That You Are Lucky is a quick and compelling read: it proceeds mostly chronologically, looping occasionally when a subject warrants further consideration, then resuming the narrative. The book reads at times almost like a novel, whose characters — the artists — are sympathetic, entertaining, delightful even; and whose plot — the constant change, growth, consolidation, removals, and adjustments of the business that is Crown Point Press — is a constantly intriguing parallel to the author's speculations on art, the making of art, and the significance that surrounds it.

The book is itself a sort of metaphor of the printmaking process, which — done well — transcends distinctions of art and craft, inspiration and dedication. She quotes the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,

who talks about the "flow" of doing something "with intense concentration on the present," so much so that you are "too involved to be concerned with failure." … "getting into the flow" is satisfying because, once you are in it, you overcome obstacles gracefully. Obstacles enhance the possibility of flow, and eventually of creativity, which flows from "flow."

Know That You Are Lucky, p. 97

This is a good description of the printmaking process, of course; it also describes the effect of Brown's writing. The first two artists she considers at length are Cage, whose method always seems so fluent, and Diebenkorn, whose method always seems so procedural. Each in his way fully represents Csikszentmihalyi's point, intensely concentrating on the present — the moment, in Cage's case — and on the procedure, with uniquely graceful results.

Among the many dialectics in Know That You Are Lucky, which is often a very philosophical book, is one involving energy and tranquility. Again, the concept flows naturally out of consideration of Diebenkorn and Cage; but also out of the nature of printmaking, of contemplation of the Zen gardens in Kyoto, of meditations on the nature of Mayan pyramids. Brown often seems to be mulling over object, context, impingements, and extension, literally when discussing imagery or methodology, figuratively when discussing the significance and the value of art — which she does always with great circumspection, never dogmatically.

She rarely writes about critics or criticism; she rarely makes what you might call critical judgments. She follows a reference to the editor Minna Daniel, who worked with both Cage and Elaine de Kooning:

I must have mentioned that I wanted someday to write about the artists I had been working with, because later I got a letter from her with advice: "Don't, for heaven's sake, ramble," she wrote. "And, if possible, avoid evaluations, which you may want to make, but they are bound to get you into a peck of trouble."and then goes on to reveal, through a delicious anecdote revealing her personal knowledge of biographical information clarifying the matter, that Willem de Kooning's late work, painted when his mind was compromised, nonetheless "reflected the person I met at dinner in 1985: open, smiling, graceful, glowing, without the bitter, desperate edges shown in his paintings from earlier times."

ibid., p. 172

On the next page she quotes Elaine de Kooning, who "felt a tremendous identification" with Paleolithic cave painters because they proved that "art was a very important part of the thought processes of the human race" before "we did go off into the left brain, codified, rationalized."

Twenty-five pages later we are in China, where Crown Point artists are working with Chinese printmakers, and we are thinking about rocks.

Rocks like the one in the hotel garden were considered enchanted in ancient China, I read later. Currents of favorable forces were thought to run through the earth and escape through places of beauty, which focused luck on those who were in contact with them. The Sung dynasty… hen the Chinese invented printing by creating the first woodblock prints, was also a time of high intellectual and aesthetic refinement that included the building of many rock gardens.Brown is slowly, imperceptibly building a persuasive argument that the making of art involves a process through which we connect to basic sources of energy and awareness that pre-exist ourselves, our society, our culture. The argument took a surprising turn, for me, when it turned to Robert Bechtle for its evidence. A characteristic image of his, of a suburban residential street, painted with Chinese watercolor on silk, was turned over to Chinese printers to translate into a wood-block print.

ibid., p. 201

To the Chinese printers, not only was this an unfamiliar scene, but also Bechtle had used unfamiliar ways of placing forms tight together and unfamiliar flat brushes to paint the forms. The craftsmen at Rong Bao Zhai had carved forty-two blocks, and they were piled up on the printer's table when we walked into the shop. We handled the blocks as if they were toys, finding a bit of a tree here, a car taillight there. We couldn't keep our eyes off the proof, it was so lively. To see the cars sitting so securely at an angle on the street, to find the light on the tree so naturally rendered — the whole thing was a real achievement. The printers and carvers stood waiting. There was nothing to do but extend our congratulations.I quote this at length partly to present Brown's graceful narrative voice, but more particularly to explain the rethinking it has caused me to undertake. Until now I've been unimpressed with Robert Bechtle's work: the technique, color, lighting, and composition are unarguably masterly, but the imagery — the "subject matter" — had always seemed inert. Same objection to another Crown Point favorite, Sol Le Witt. But when Brown returns to John Cage — whose work I have always found meaningful and inspiring — she brings me up short, forces me to confront my prejudice.

"I really couldn't think of anything that could make it better," Bob told me later. "I found the whole thing rather emotional. There was such a powerful sense of place, and the character of the people was so strongly present."

ibid., p. 205

He named [the print Smoke Weather Stone Weather ] for the weather, which, as he said, "remains the weather no matter what is going on." He said he "didn't want to have an image that would separate itself from the paper."Exactly. It's not a matter of imagery, of subject matter, of personal judgments about energy or relevance or inertness. The taillight, the banal street, have the intelligence and the energy of the Chinese rocks — or the rocks, for that matter, that Cage uses in so many of his prints. A few pages on Brown is telling us about the Danish artist Per Kirkeby, a geologist incidentally as well as painter, sculptor, printmaker, and writer, who

ibid., p. 241

has said that painting is "the real reality" behind the "so-called reality" of our everyday experience. "We only see it in glimpses."The life that Kathan Brown, herself, lives, has been devoted to both Art and Business, and her accounts of the articulating moments in the fifty-year history of her business are of great interest. Earthquake, renovation, staffing crises, national prosperity and recession, the foibles and fashions of the retail art business — these have an important place in her narrative, tethering speculations on perception and philosophy and aesthetics to "real-world" considerations of employment and compensation and community.

I understand the notion of seeing reality in glimpses, and I like the idea that Per Kirkeby (like John Cage and a few other artists we have published) has been successful in more than one line of work. But I am not sure that any one reality is more real than any other. I like looking at art, and the realities I absorb from art influence the life that I, myself, live.

ibid., p. 257

And no narrative of the second half of the twentieth century can neglect significant changes in the way we deal with art, reality, business, perception.

I told [the artist Brad Brown, born in 1964] Cage's story of an argument he once had with de Kooning in a restaurant. There were bread crumbs on the paper-covered table and, drawing a line around them, de Kooning said, "That isn't art."Brown refers to Tom Marioni's idea of "a collective reality," and, a few pages later, to

"But," John explained to us, long ago at Crown Point Press, "I would say that it was." In his eyes, de Kooning had made the bread crumbs art by selecting them and framing them, but in de Kooning's eyes he had made a point, not art. I said to Brad that to me Cage and de Kooning are essentially incompatible. Brad said he hoped to adapt both of them to his own ends. This is different from how my generation learned to pursue knowledge. Ideas come now in bits and pieces, not in a continuum where one idea leads to another or is necessarily compatible with another.

ibid., pp. 290-91

The Diamond Sutra, the world's oldest printed book, [which] was found in a cave at Dunhuang. It was printed in 868. Here is a stanza from it:She quotes the photographer John Chiara, who says of his long-exposure work with a huge camera he invented and built for himself, "There's a noise in the process that I think is revealing and meaningful… It's like the failure of memory."

This fleeting world is like a star at dawn, a bubble in a stream, a flash of lightning in a summer cloud, a flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

ibid., p. 301

She wonders, near the end of this haunting book,

In 2012 we are only slightly into our new century. What does each of us need to know in order to survive as long as possible, however tenuously? Is three a common denominator that artists are searching for? If so, could it be, as Laura Owens has said "an aura of acceptance of whatever has happened"? Could it be hopefulness?which returns us to a quote she presents near the very beginning of her book, from Montaigne: "The most manifest sign of wisdom is continual cheerfulness."

ibid., p. 307

I have quoted very extensively here from Know That You Are Lucky; this is less a "review" than a "reading through," and I hope Kathan Brown won't mind. The book contains much that I haven't touched on, of course. To me it deserves a place next to Carolyn Brown's magnificent memoir Chance and Circumstance, which I touched on a year or so ago here but have yet to deal with properly. (Perhaps one day.) Memoir is by its nature retrospective and even, in these two books, a little bit valedictory — though I wish these authors long futures; they still have things to tell us.

As I've said in other contexts, one of the most impressive things about their work is its great generosity. Long careers, full lives, great dedication, methodical application, vision, insight. Wisdom beyond words.

•Kathan Brown: Know That You Are Lucky. 376 pages; index; forty-seven color plates.

San Francisco: Crown Point Press, 2012; ISBN 978-1-891300-24-0