•Handel: Agrippina.

•Janáček: Příhody Lišky Bystroušky

(The Cunning Little Vixen).

•Thomas Adès: Powder Her Face.

Seen at West Edge Opera, Oakland,

Aug. 12-13, 2016

|

|

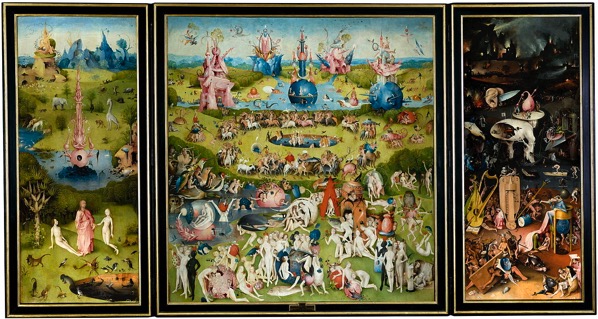

| Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1500, oil on oak panels, 220 cm × 389 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid |

Eastside Road, August 17, 2016—

A COUPLE OF young men meet in a London pub, strike up a conversation, and have a few drinks. They're guys: the conversation inevitably turns to sex. They agree on most points. Sex is a natural component of animal life, after all, and if its expression, in individual activity, results in social criticism or disapproval, that says more about social neuroses than individual maladjustments.

But after a few drinks the brash young Londoner is impatient with his new friend, a German who’s just arrived from a few years spent in Italy. The guy has been around, he dresses fashionably, but his ideas seem conventional, even provincial, and he's a little priggish. Born at the height of the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and '70s, the Englishman points out that civilized restraints on sexual behavior only encourage hypocrisy. The only positive contribution made by this repressiveness is the entertainment value it provides to the tabloids.

The immigrant isn’t so sure. His father was a surgeon; he knows what happens to the bodies of dissolute youths. He’s spent time in the Vatican and in major and minor power-centers in Germany and Italy, and he knows a lot about intrigue and betrayal. A child of the Enlightenment, the turns to Roman history for his discussion. It was a disgusting time, first-century Rome, lacking all civilized restraint, celebrating power and cruelty. Among humans, the pursuit of pleasure too easily becomes compulsive. It leads to social decadence and personal ruin, and must be restrained. You don't want your London to turn into Imperial Rome.

A rather shabby old man listens quietly, musing about the irony of his own situation. These two youths are out of his league. His English has a strong Czech accent. He’s a small-town schoolteacher, not a social butterfly; he loves the forest, not cities. He's been contentedly married for many years — yet he's become obsessed with an idealized kind of love for a younger woman, also married — and at a time when sexual performance is no longer relevant.

The bartender's been listening to the conversation, as bartenders do, and finally makes a comment of his own: You could write a novel about all this, he says, or even an opera.

THE BARTENDER IS Mark Streshinsky, General Director of Berkeley Opera, which produced the results of this conversation this last month. West Edge has settled into an interesting formula, presenting in repertory, in a three-week season, three operas: one from an early era, performed with period instruments; one from the neglected standard-repertory period; one new or relatively new title. (Last summer these were Monteverdi's Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Alban Berg's Lulu, and Laura Kaminsky's As One, discussed here August 3, 2015; next year we are promised Vicente Martin y Soler's L'arbore di Diana, Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet, and Libby Larsen's Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus.)

The operas were produced in an evocative space, Oakland's "abandoned train station," a Beaux-Arts building designed by Jarvis Hunt, opened in 1912 by the Southern Pacific Railway, closed following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, bought ultimately by the developer Bridge Housing, and planned, it is to be hoped, to be retained for public use. (The symbolism – a grand public building erected a century ago for commercial purposes, abandoned and allowed to decay, then stabilized and restored as a nostalgic if somewhat sketchy place for the performing arts — invites comment: but I digress.)

A distinctly musky fragrance hovered in this architectural curiosity last weekend, when we saw the final performances of this randy triptych: Agrippina, composed in Naples by the then 24-year-old George Friedrich Handel in 1709; Vixen Sharp-Ears (a better translation than The Cunning Little Vixen ), completed in 1923 by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček, then just shy of seventy; Powder Her Face, composed by the 26-year-old Thomas Adès in 1996.

AGRIPPINA WAS STARTLING from the moment we entered the theater: the stage was fronted by an enormous enlargement of Hieronymus Bosch's own triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, so large the figures in the lower corners of the central panel — whom we came to feel we knew — were life-sized. The overture, conducted from the harpsichord by Jory Vinikour, was gripping: suggestive in its slow tempi, thrilling in the fast.

Vinikour's orchestra comprised three each of first and second violins, two violas, two cellos, one bass viol, two players doubling on oboes and recorders, one trumpeter, and, most effectively, Richard Savino playing theorbo in the basso continuo. I've read that the original orchestra included contrabassoon and timpani; I missed the latter, and wonder what the former would have done. In any case this orchestra was captivating.

Mark Streshinsky's staging was perhaps in the style of the original, staged in Venice. The plot concerns Agrippina's plots to elevate her son Nerone to the Roman throne after the reported death of the emperor Claudio. Other characters include Claudius's friend Ottone; his inammorata Poppea (desired also by Claudio), Agrippina's two feckless assistants Pallante and Narciso, and Claudio's servant Lesbo. (I reproduce the Italian names: Nero and Claudius are the more familiar English forms.)

Of this crew the only decent person is Ottone; the others range from Claudio's woolly-minded covetousness, through Nerone's impressively indiscriminate appetite, to Agrippina's truly evil manipulativeness. The entire cast was thoughtfully chosen, directed, and costumed: this production was well conceived and integrated. Until I saw Powder Her Face, the next evening, I thought Streshinsky's direction had gone over the top: the central intelligence, I guess you'd call him, was Nerone, whose unfocussed amorousness was like a totally immoral Cherubino. His mother Agrippina was infected with the same virus, and you could see that while the rest of the cast, even Claudio, had misgivings about this, they found it irresistible.

Perhaps because I'm a prig I found Ryan Belongie's portrayal of Ottone the high point of the evening. His counter-tenor voice is strong, sweet, clear, and affecting; his lament was the finest moment of the evening. This is unfair to other performers, who seemed almost equally to occupy their roles, with almost equal gifts and technique: Celine Ricci as an androgynous Nerone, Sarah Gartshore in the disgusting title role; Carl King as Claudio; Nikolas Nackley, Johanna Bronk, and Nick Volkert as Pallante, Narciso, and Lesbo.

Musically, these singers, and their orchestra, made this a marvelous evening. Visually, Sarah Phykitt's set design, Kevin Landesman's lighting, and Alice Ruiz's intriguing costumes anchored Streshinsky's thoughtful, playful, completely amoral direction. I'm not sure what Handel's father would have thought.

VIXEN SHARP-EARS is one of my very favorite operas, if I may make a personal remark. I have always loved Janáček's spiky, evocative, quite original music, whose roots lie in Central Europe's 19th century, but whose individuality reaches far into the twentieth century, toward such other total individualists as, for example, the Italian Giacinto Scelsi. Janáček's gifts for melodic rhythm, harmonic sonority, and instrumental technique are overwhelming, and like Handel he brings these essentially instrumental qualities to a very sympathetic ear for the human voice.

He composed a number of operas, but to my taste Vixen is the best, partly for its musical compression and inventiveness but especially for the great, deep humanity of its subject, expressed through the composer's own adaptation of, of all things, a graphic novella (a sort of comic strip) that appeared in a Prague newspaper for a few months in 1920. The story is simple: a young vixen cub is captured by a forester, escapes back to the forest after growing to maturity and attacking the henhouse, couples with a fox with whom she raises a number of cubs, is shot by a hunter.

There are three principal roles: Vixen, marvelously sung and acted by the soprano Amy Foote; Forester, strongly and engagingly represented by the bass Philip Skinner; Fox, particularly sympathetic in the performance of mezzo Nikola Printz. The large cast also includes a frog, several hens, a cricket, a goofy dog, and Vixen as a cub; these roles were taken by members of the Piedmont East Bay Children's Choir.

I've seen three productions of Vixen that I can think of, all of them quite different solutions of the staging problem of rendering animals (and insects even!) both natural and sympathetic without resort to anthropomorphism or sentimentality. Two things are crucial to success: costuming and makeup, here ably rendered by Christine Crook, Alice Ruiz, and Sophia Smith; and physical acting, credited in this production to Pat Diamond (director) but achieved for the most part compellingly by each actor, even — perhaps especially — the children.

First, last, and center, Vixen Sharp-Ears is about Life. Life as a natural force, a force so general that it overcomes individual life and death, spans time-periods beyond individual lifetimes, addresses ethical realities beyond human desires and frustrations. The one overwhelming instinct is to be free, and you can take Janáček's meaning to include individual, political, moral, and economic freedom; freedom from the conventional restrictions of social class and position, but also freedom from the constraints most of us manage to create for ourselves every day as we substitute comfort and convention for vitality and instinct.

I have to confess that after seeing Agrippina and reading about Powder Her Face I was worried about what West Edge might do with Vixen. It would have been easy to sell the opera short, to sensationalize the sexual component, to trivialize the humanity. But Diamond's direction respected the intent, I think, of the original creators; and Foote, Printz, and Skinner beautifully conveyed the depth and reach of the moral and ethical issues. (So did Joseph Raymond Meyers as the dejected Schoolmaster and, in a more comic approach, Carl King as the drunk poacher Harašta, who shoots Vixen.)

Janáček's score was brilliantly performed, in a reduced orchestration by Jonathan Dove, by Jonathan Khuner, leading asixteen-piece orchestra. Janáček needs a lot of notes for his music, and this orchestra was kept busy: I was particularly impressed with the five string players, but the winds were equally up to the task. What a fine, far-reaching, lasting opera this is; what a fine job West Edge did with it.

POWDER HER FACE failed to interest me. Thomas Adès and his librettist Philip Hensher (also a Londoner, five years older than the composer) collaborated on it deeply under the influence of Alban Berg's opera Lulu and Igor Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, and the result seems to me greatly over-worked, too self-indulgent about inner jokes and allusions, and too ready to excuse its own undisciplined bawdiness with the pretext of ironic social commentary.

The story is that of the Duchess of Argyll, whose compulsive fellatios with strangers were a tabloid scandal in the mid-1950s, and who apparently lived an increasingly pathetic descent into reclusive poverty over he next thirty-five years. This "rake's progress" unfolds through five scenes in the first act, four in the second. I can't comment on the second act; we left at intermission.

We left for two reasons: the action of the opera, at least in this production (but inescapably, judging from the plot summary provided), was tediously jokey and in-your-face; worse, the music was unrelievedly busy, strident, and loud. Stage routines ran the gamut, as Dorothy Parker would have written, from A to B: soft-core pornography to lewd comedy. Laura Bohn, as the Duchess, might have been sympathetic but was rarely given scope by either composer or director. Hadleigh Adams was two-dimensional, whether as Duke or Hotel Manager. Jonathan Blalock was perhaps the most successful singing actor by virtue of his role, which allowed him some individuality. Worst of all, Emma McNairy, who was such a splendid, musical Lulu last summer in Berg's opera, was made to shriek at virtually every opportunity.

Mary Chun worked hard to open the busy, opaque textures of the score, and her fifteen-piece orchestra, the contemporary music specialists Earplay, played their hearts out. But I have to believe these gifted singers and musicians, and stage director Elkhanah Pulitzer, did all this in the service of the opera, but they had little help from composer and librettist, who seemed to want to spend endless talent and intellect and awareness of precedent on a silly, one-dimensional, deliberately vulgar piece of theater.

Adès's score has a number of arresting ideas, but except when they're repeated too often — the baritone saxophone bleat, for example — they're too often lost in the crowded, overly busy orchestration. And the vocal writing doesn't work: you can rarely understand the sung English (thank heaven, I suppose, for the supertitles), and the extremes of tessitura are physically painful.

But then I'm an old man, my tastes and sympathies much closer to the Forester's than the Duke's. I'm grateful for the opportunity to have heard half of this opera, I think; and I respect the intellectual content of this three-opera season, whose effect only makes sense, I think, thanks to the triangulation provided by Vixen.

Motherwell is around the corner to the left from Mark Rothko, whose characteristic red-over-black has the requisite weight and mystery to hold its own among strong company — the Joan Mitchell and Jay DeFeo canvases to its left, and, across the gallery, equally strong work by Philip Guston.

Motherwell is around the corner to the left from Mark Rothko, whose characteristic red-over-black has the requisite weight and mystery to hold its own among strong company — the Joan Mitchell and Jay DeFeo canvases to its left, and, across the gallery, equally strong work by Philip Guston.