| •Bhishma Xenotechnites: Monochord Matters: or, The Power of Harmonia.. Online here at http://shere.org/Leedy/MonochordMatters.pdf; 19 pages. |

He is reclusive, having long ago developed a thorough scorn for Western Civilization — he would put that last word in quotes — and having developed an intense pessimism on the likelihood of our planet surviving the terrible things humanity is doing to it. And because he is reclusive I'll say no more about him at present; it feels like betrayal having gone even as far as I have.

I do want to make it known, though, that he has published what I think is a significant monograph on a subject of considerable interest to him, as both musician and classicist. I had something to do with the publication, as I had volunteered to set it in (computer) type and arrange for placement on the internet.

The monochord, a single string, as the word suggests, stretched over a resonating block or box, is, Xenotechnites suggests, one of the oldest technological inventions. It was used by the Greeks for the exploration of ratio and proportion, and stands, I would say, at the intersection of music and mathematics, of concrete demonstration and abstraction, of reason and mystery.

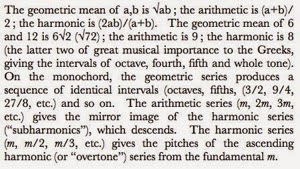

In a series of eighteen or twenty short sections, inspired perhaps by Wittgenstein and Whitehead, Xenotechnites elegantly describes the implications of the Hellenic discoveries. Of course there is a great deal of technical matter in his description, and I'm afraid my typesetting could go only so far in rendering the discussion either clear or attractive to a lay reader. Yet some of these items have astonishing beauty and arrest the reader with their insight and vision:

In a series of eighteen or twenty short sections, inspired perhaps by Wittgenstein and Whitehead, Xenotechnites elegantly describes the implications of the Hellenic discoveries. Of course there is a great deal of technical matter in his description, and I'm afraid my typesetting could go only so far in rendering the discussion either clear or attractive to a lay reader. Yet some of these items have astonishing beauty and arrest the reader with their insight and vision:14. Mathematics "is given to us in its entirety and does not change, unlike the Milky Way. That part of it of which we have a perfect view seems beautiful, suggesting harmony." (Kurt Gōdel, quoted in Palle Yourgrau, A World Without Time (Basic Books, 2005), 184.)As that quotation shows, Xenotechnites ranges wide among his source material, quoting Homer, Lady Murasaki, the composers J.J. Quantz and John Dowland, Pythagoras, and Claudius Ptolemy; and going to Aristotle, Helmholtz, and Wittgenstein among others for his own instruction. Xenotechnites is comfortable in ancient Greek and Latin, and reads well enough in a few modern European languages. He respects his sources, quoting them in their original languages as well as in English translation (generally his own).

I can't pretend to grasp the mathematical and philosophical implications of Xenotechnites's monograph, but I can admire the clarity and beauty of his prose style, through which I can glimpse, I think, what he is getting at:

The proportional relationship of two string-lengths we know as a ratio, the Latin word that also means reason (the Greeks’ word was logos, a word with many other meanings). We apprehend the musical interval between the pitches through the faculty of perception, and we note the relationship of string-lengths associated with that interval through the faculty of reason, which we can expand into principles that qualify under the modern meaning of “scientific.”If I think I can glimpse the substance of this fascinating argument, then I think almost any reader will. I believe Xenotechnites comes close to poetry here, the kind of poetry that is close to philosophy that Charles Simić was contemplating in my previous post. I repeat: Monochord Matters is, I think, an important piece of writing, as well as a beautiful one, even, at times, moving.