"Songs move through time, seeking their final form. What happens on that path is only partly up to the writer, the singer, the musicians. It may be partly up to the audience hearing the songs, watching them as they are performed, with the response of the audience, even of a single member of the audience, coming back to the performers…"—Greil Marcus, writing of "Bob Dylan, Master of Change," in the New York Times, October 13, 2016

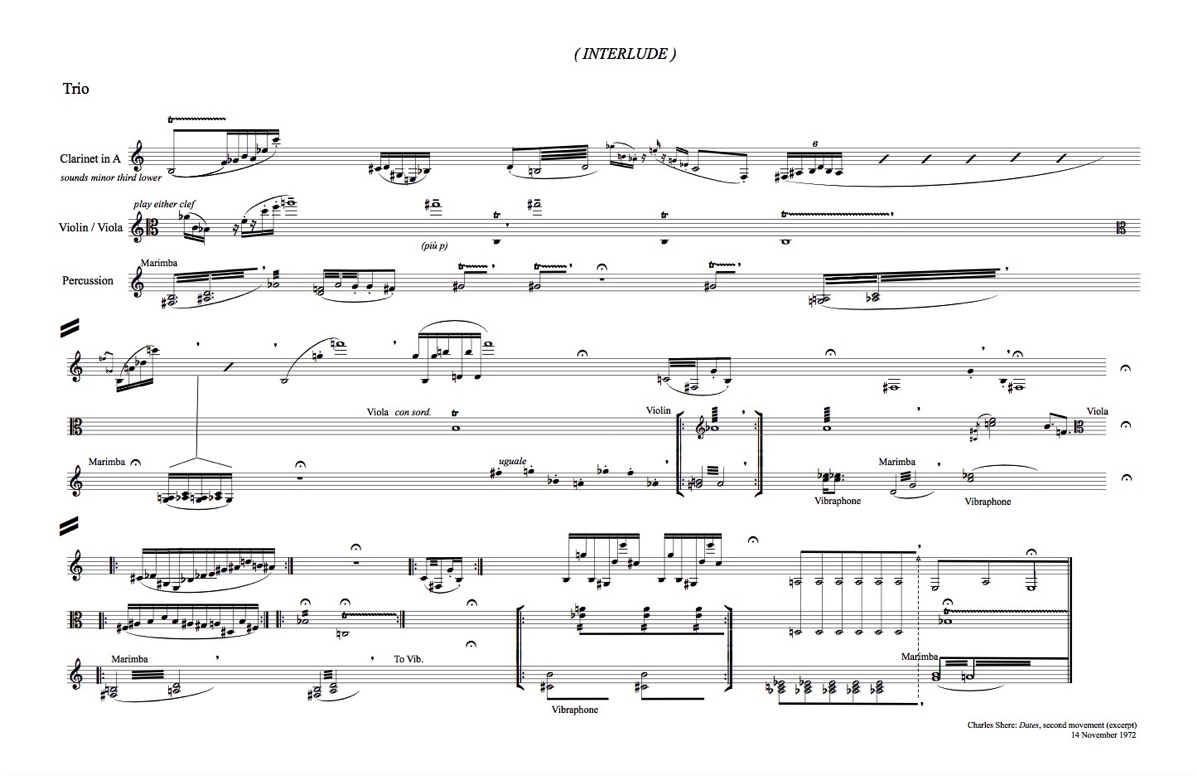

FOR A NUMBER of days I've been working a few hours at re-notating a piece I wrote in 1974: Dates, a sort of chamber cantata for soprano and three instrumentalists, to Gertrude Stein's poem collection of that name.

The notation has not been easy, because the original notation is not completely conventional. Much of the piece is in mobile form, meaning that the musicians are given a certain amount of latitude as to just when they play their notes. (The name comes from Alexander Calder's hanging sculptures, whose shapes take various overlapping configurations literally depending on which way the wind blows. Marcel Duchamp referred to these sculptures, when they first appeared, as "mobiles," and the name stuck.) The notes themselves are stipulated, as well as the order in which they are played; but I wanted to give them precisely the freedom Greil suggests "songs" themselves have, the freedom to seek their own final form. "Final," it must be added, only provisionally, for that one performance.

Mobile form, like the related "open form," is of course one of the conventions that developed in the 1950s and '60s, when musical composition was finding new energies in its dissatisfaction with the constraints of traditional musical forms and organization of pitches (whether tonal or serial). You might call it is a conservative view of the indeterminacy of sounds pioneered by John Cage. I think of it as a way for the composer to moderate his authority and perhaps suppress his ego.

Perhaps there's an analogy with the method Stein employed to write her poetry. She worked late at night, alone of course, in the silence of her apartment, at her writing desk; but I believe she recalled words she'd heard or overheard in the course of the day, letting them appear as they would among other words taken from previously published sources, or in the continual process of meditation.

Dates was written for a concert I helped organize in February 1974 on the occasion of Stein's centennial birthday; but also for my friend the clarinetist Tom Rose, who needed a new piece to play for his postgraduate degree at Mills College, where I was then teaching. I added two other instrumentalists to the mix, both then also teaching there, both now alas no longer with us: the marvelous violinist Nathan Rubin, who doubled easily on viola, and the engaging yet serious percussionist Jack van der Wyk.

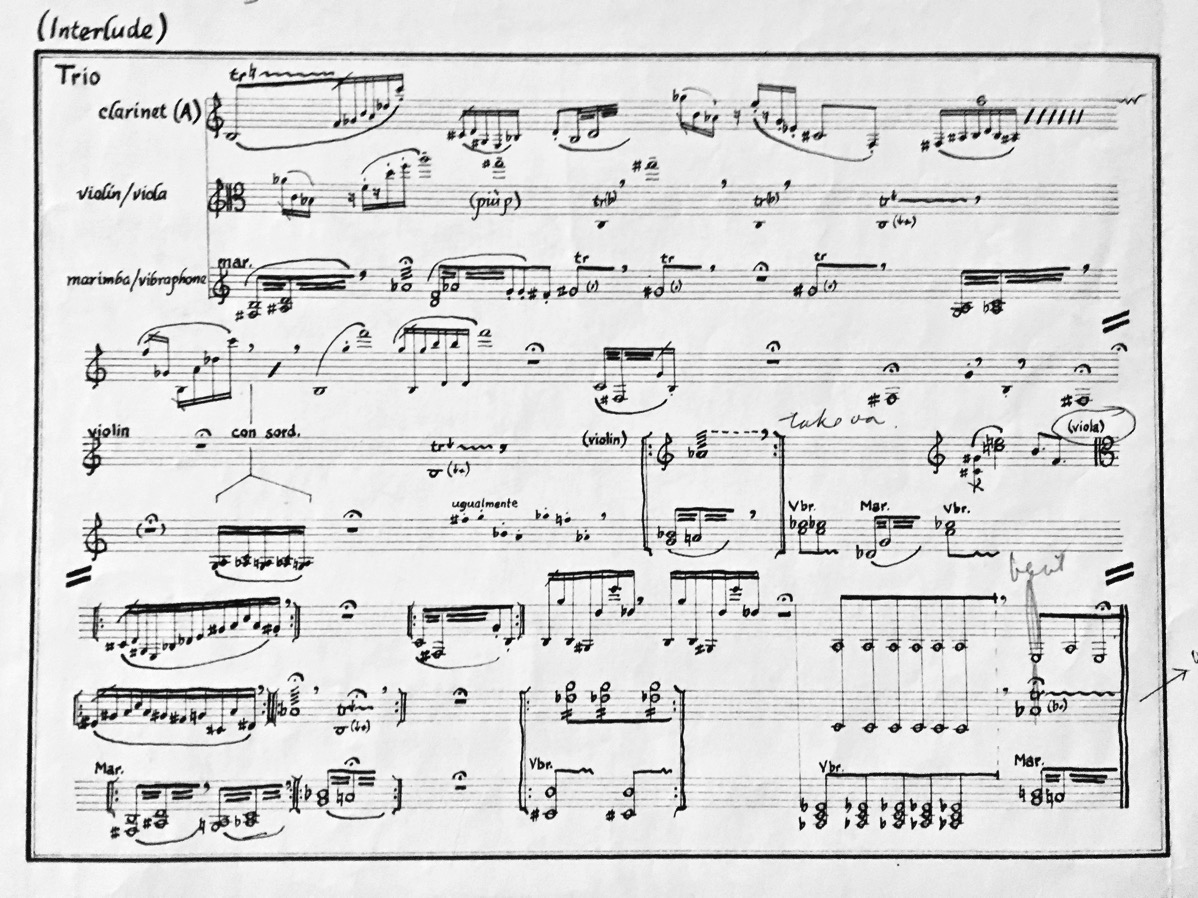

The cantata is in three movements and runs to nearly fourteen minutes in the one recording I have. (Since it is in mobile form the possible duration of the piece can vary within limits.) Today I'm sharing only a minute and a half of the piece, to illustrate the mobile-form concept. The score is reproduced above; you can listen to the excerpt here. (This performance features the late Judy Nelson, soprano, and the instrumentalists for whom the music was intended: Tom Rose, Nathan Rubin, Jack van der Wyk.)

The recorded excerpt opens with the last words of the fifth poem in the cycle, then immediately moves into the Trio shown above, on which the soprano superimposes the sixth poem:

5:

Spaniard.

Soiled pin.

Soda soda.

Soda soda.

6:

Wednesday.

Not a particle wader

Aider.

Add send dishes.

I'll have more to say about Dates, perhaps, when I've finished notating the entire score. I reproduce below the original manuscript of this excerpt…