|  |  | |

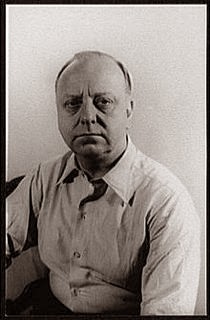

| Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) | John Cage (1912-1992) | Lou Harrison (1917-2003) |

In 1965, I think it was, Lou brought Virgil Thomson to our Berkeley apartment, on Francisco Street, for conversation, and from then on both men were occasional friends, I suppose you’d call them — Lou lived in Aptos, Virgil in New York; I was working double-time at KPFA and trying to compose on the side, not to mention keep the car running and the plumbing in line, all those things you do when you’re raising a family on $75 a week in a one-bedroom duplex, studio in the basement.

Chez Panisse opened in 1971, and it wasn’t long before Virgil came to dinner. I remember his liking Lindsey’s crème anglaise, complimenting her on how little cornstarch she’d used in it. Alice was shocked: Oh no, she said quickly; there’s no cornstarch in that crème anglaise. Lindsey smiled quietly: there was a tiny bit of cornstarch in it; subsequently she worked out a method that dispensed with it entirely.

We never went to New York, and still don’t, not having formed the habit. But Lindsey spent a few days there every few years on business, and when we were there we always visited Virgil in his rooms at the Chelsea Hotel. We talked about mutual acquaintances, about the old days, about Mozart, about criticism — I was by then working as an art and music critic, and was interested in that often-reviled and usually badly practiced profession.

By the early 1980s we knew John Cage well enough, Lindsey and I, to be on a first-name basis. In that decade I was working on a series of composer’s biographies for Fallen Leaf Press: I completed the first, on Robert Erickson, and got halfway through the next, on Lou. I was projecting one on John, too, and visited him a couple of times in his New York apartment, helping him make our lunch, talking about Duchamp, about Buddhism, about cuisine, about criticism.

I dropped the book about Lou after about 50,000 words, when I’d brought him up to his fiftieth year, when he was well settled with Bill Colvig, reasonably accepted in his corner of the music world, and had begun dedicating himself to gamelan, a music that didn’t interest me. By then it was clear Lou would not need my help in being presented to the wide world; that was well begun. Even less would John need a biography from me: a number were already in preparation as he approached his eightieth year.

Serious biography of this sort requires detective work, solid musical analysis, real focus, and discipline — all qualities I have little familiarity with and, in fact, little enthusiasm for. Besides, unlike Erickson, both Lou and John had lived within a social context I knew nothing about. Most of all, I very much liked both of them, and treasured them as friends and colleagues, a relationship I sensed would be endangered were I to continue further in a biographer’s role.

Lou and Bill visited us up here on Eastside Road a couple of times, and we continued to see them now and then in their Aptos house. (I remember one visit, when I was examining their house more attentively than usual, and Bill noticed. We were then planning our own house. I asked Bill whether he thought I should frame it in two-by-fours, the conventional approach, or two-by-sixes. “How long do you want to live in it?”, he responded; and we framed it in two-by-sixes.)

We saw Virgil and John, or Virgil or John, every couple of years, on those New York visits, or occasionally when one or another was in the Bay Area. If it was John, well, he was always busy, and we saw him in passing. He and Virgil were quite different in that respect: John was focussed, dedicated, disciplined, driven; Virgil was retired, sociable, at ease. I must say I preferred his style, though I respected and envied the other’s production.

The last time we visited Virgil at the Chelsea was a year or two before his death. He was quite old — he died in 1989 — but he was reasonably healthy as far as we could see. He mentioned that his sister had died at the age of 94, and he was certain he would not outlive her, and he turned out to be correct: he was two months shy of that age. I asked him if there were any way he could be reconciled with John. Not quite in those words, I suppose, but close. I was thinking about the idiotic rift that had set in between Satie and Debussy; how Debussy had died without seeing Satie again, and there was something in the Debussy-Satie relationship that had always rhymed, so to speak, in my mind, with the Thomson-Cage relationship. So many hours working in the trenches together, so many “values” in common, so much good conversation and shared experiences, all thrown away over some momentary thing. Virgil was not interested: John had gone his own way. I think perhaps in the end the hardest thing for Virgil was the progress, if you can call it that, of musical Modernism, away from his own day, into areas for which he had no interest, which were simply not to his taste, as gamelan is not to mine.

That same summer I saw John in his apartment. We had lunch together. We shelled peas, I think it was, or beans, and laughed at the cat on the catwalks, and talked about one thing and another. My problem with such interviews was always that there were so many things unsaid, because we both knew them, and agreed about them, why discuss them?

I did mention Virgil, though, and wondered why they wouldn’t speak. John was obstinate. The least you can ask of people, he said, is loyalty.

Certainly two events fed this feud. One was the early life-and-works book about Virgil, published as Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, Publisher; 1959). The book is published as having been written by Kathleen Hoover (the Life) and John Cage (the Music). A number of rumors fly around the book: John wrote it all, Virgil didn’t like the Life section and assigned it instead to Hoover. Or: Virgil wrote it all, and assigned the credits away to mask self-promotion. Or Virgil extensively re-wrote passages. I hate waspishness, and you deal with a certain amount of that when you negotiate these waters. In any case, it’s impossible to get to the bottom of such things; there are many truths.

The other event was Virgil’s review of whichever piece it was of John’s, I forget now, either 4’33" or the Variations (if that’s what it was titled) that involves a number of radios, that pushed John’s musical ideas beyond the threshold of Virgil’s limits — beyond, I mean, what Virgil’s sensibility and training allowed him to consider musical.

As late as 1962, in the introduction to the Peters Edition catalog of his music (called, simply, John Cage), John gracefully thanked Virgil (along with Peter Yates) for his understanding criticism. Criticism is at the center of the Virgil-John situation, and indeed to the Virgil-John-Lou group, to which in all humility I would add, at times, myself. I have always cherished and often cited the late Joseph Kerman's memorable, terse definition of the practice: "the study of the meaning and the value of art works." (Contemplating Music: challenges to musicology, Harvard University Press, 1986).

Virgil, John, and Lou, with a few others — Peggy Glanville-Hicks among them — created a community of criticism in that very sense, under Virgil’s direction, at the old New York Herald Tribune, in the years following the end of World War II. I don’t have patience to go further here into the extraordinary ferment of intellectual and artistic energy and knowledge present then and there: it was a moment like Paris, 1911-1928, or Vienna, 1770-1820. Such moments cannot be forced; they can only be exploited, and Virgil Thomson had the perfect intelligence and sensibility to understand that, and contribute further to it.

But criticism has its negative aspect, particularly when considered as it affects individuals, whether they are practicing it or responding to it. The Herald Tribune Virgil group, to call it that, comprised composer-critics. Who better to respond to music than a musician? But pride and sensitivity are easily involved, and the biographical results can be sad to contemplate.

No comments:

Post a Comment