Eastside Road, July 7, 2011—

IN THE SUMMER of 1916, ninety-five years ago, in Paris, Jean Cocteau took two dozen photographs of a number of friends. Sixty years later, in 1978, the Swedish-born artist Billy Klüver (1927–2004) (whose name is familiar to me from the Experiments in Art and Technology days), while he was researching documentation concerning the art community in Montparnasse in the early Twentieth Century, noticed that a number of photographs, found in various sources, fell into groups. Curious, he began investigating. Ultimately he was able to determine the sequence, location, date and time of the original exposures — and, of course, the identities of the people depicted.Reading the most recent publication of the result of Klüver's work reminded me of one of my childhood fascinations, the recurring feature Photoquiz in the old Look magazine, which for a time my grandparents apparently subscribed to — uncharacteristically, it seems to me. Or perhaps more buried recollections of photo-sequencing components in intelligence tests I was subjected to in those days: you look at a number of photos and try to figure out the chronological sequence in which they were taken.

(Now that I think of it, these kinds of quizzes, along with the popular side-by-side “how do these differ” cartoons in the Sunday comics, all components of my childhood, are all examples, or instructions, in a preoccupation I've been developing lately concerning The Search for Meaning.)

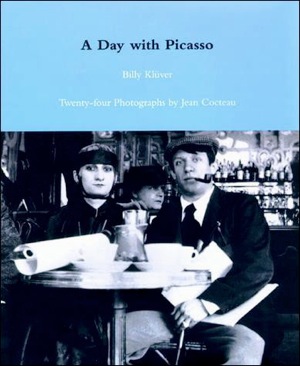

Klüver's research was published here and there: sections in the magazine Art in America in September 1986, then in book form in German (1993) and French (1994). The American English-language edition, A Day with Picasso, was published in a handsome edition by MIT Press in 1997, then in paper in 1999. I find it thoroughly fascinating.

The book centers, of course, on the two dozen photographs, nicely reproduced — one can only wonder how much work went into restoring this ancient testimony to a summer day among friends. Eleven of the negatives survive in the Cocteau archives; another nine negatives are lost but original contact prints were also in that archive. Two photographs turned up in reproductions in old periodicals (Paris-Montparnasse, May 1929; Bravo, December 1930), and two others were found in other archives.

Some of the people in the photographs are easily identified: Picasso, Max Jacob, Modigliani. Through a series of interviews with surviving friends and associates of theirs, Klüver was able to identify the others. With the help of old cadastres and maps, and the French Bureau des Longitudes, he was able not only to determine the places depicted, and the probable camera locations, but even the time of day. Interviews and other research had already isolated the only possible date on which all but two were taken: Saturday, August 12, 1916.

(When recently did I read Ken Alder's The Measure of All Things, about that Bureau among other things, and why did I not write about it here?)

The MIT Press edition of A Day with Picasso includes as well as the photographs themselves, with nice running commentary, chapters on the methodology of Klüver's research, the dating and timing, the means whereby the model of Cocteau's camerawas determined, biographical notes on the people photographed, the Paris of the time, and the Salon d'Antin, where Picasso's Les demoiselles d'Avignon (as it was then retitled) was first shown publicly — this particular group of friends and acquaintances were together to some extent because they were all involved with that exhibition.

All this is extremely interesting. History, photography, research, methodology, and the essence of Community are the matter of Klüver's book, and he touched them all lightly yet thoroughly, and reveals how History is — not made, or written, but teased out.

A Day with Picasso is still in print, as far as I can tell. Since its publication in English, editions have appeared in Japan, Korea, and Italy. Klüver's Montparnasse researches resulted also in Kiki's Paris, about the legendary artist's model Kiki (Alice Prin); it was published in the U.S. in 1989 and went on to editions in France, Germany, Sweden, Spain, and Japan. He also co-edited and annotated Kiki's own memoirs, which appeared in 1930 but was then refused entry into the U.S. If these books are as graceful, informative, and entertaining as A Day with Picasso, I want to read them.

No comments:

Post a Comment