|

|---|

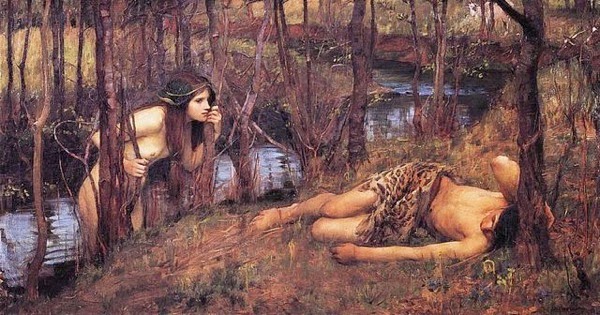

| John William Waterhouse: Undine (1872) |

Misgivings first, to get them out of the way. Operas are written and generally produced to be seen and heard in a theater, the audience removed from the action. The voices, the expressions and gestures, the sets and costumes are designed to overcome the softening and "blossoming," you might say, that comes with distance. In the opera house the sound engulfs me. But in the movie theater it comes at me very clearly from loudspeakers front left and right. I see too clearly the mesh of the nets to which stage decor is attached. Closeups, no matter how beautiful the subject and how persuasive his expression, rob me of glances at the supporting actor standing just out of sight.

Still it must be said this Rusalka was beautifully and persuasively sung, acted, cast, and for the most part directed; and were surprised to hear the mistress of ceremonies, Susan Grant, seem to apologize for the physical production: we thought it remarkably apt.

One of my biggest complaints about these broadcasts-into-the-movie-theater is the treatment of the intermissions. Those interviews, well-meaning and "educational" as I suppose they are, intrude on my experience of the integrated work of art that is the opera. But it was amusing to watch the stage crew laboring at the complex and ambitious change of scene before the third act; and I was interested to hear the conductor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin (French-Canadian, bio here) talk about the opera with his youthful enthusiasm.

I thought the principals well cast and in good form: Renée Fleming in the title role; Piotr Beczala as the Prince; Dolora Zajick as the witch Ježibaba; John Relyea as the Water Gnome; Emily Magee as the Foreign Princess. The orchestra played well, with a good central European sound, I thought.

It's startling to consider that Rusalka is, technically, a twentieth-century opera, having been completed in 1901. There's no doubt about certain Wagnerian influences; you are reminded of the "Forest Murmurs" from Siegfried for example: more deliciously, Dvořák actually parodies Wagner from time to time — notably in the three ladies ho-jo-to-ho'ing about friskily at the opening. In the end, though, it's not Wagner but Janáček, of all people, who I think about on leaving the theater, Janáček of The Cunning Little Vixen.

This is not entirely because of the sound of the opera, of course: it's the opera in its entirety that does this. To me, this production of Rusalka is a totally integrated success: visual production, score, libretto and the performances merged into a serious and profound presentation of the water-nymph narrative — which is well worth contemplation.

THE MEME OF THE NAIAD goes back to prehistory, when everyone must have known the primal significance of water, without which life is impossible. Nothing more sacred than a spring — how many such mysterious, resonant, sacred places there must have been, articulating the wanderings of early nomadic humans, anchoring settlements as they began to appear.

And nothing more mysterious, I suppose, than the underground movement of water, rivers appearing out of nowhere and, occasionally, disappearing into the ground for no apparent reason, perhaps to re-emerge elsewhere. And, always, the vitality of the water, whether flowing animatedly or profoundly still yet somehow pregnant with sustenance.

And, mercurial and capricious, the waters can be dangerous and sinister as well as sustaining and nourishing. This is particularly true of the still forest pools, sometimes surprisingly, even unknowably deep, often with marshy edges, sometimes edged with treacherous quicksands. To this day there are sinkholes, filled with stagnant water, that are dreaded by the folks living nearby — I remember one we visited in the Var, in Provence, said to have been inhabited by a spirit who lived on the bodies of babies snatched from its edge.

On getting home from the opera Saturday I fetched down from the shelf a book I hadn't looked at in a number of years but remembered fondly, a child's edition, in English, of Undine, written in 1811 by the German Romantic novelist Friederich de la Motte Fouqué. (The edition I have is "retold" by Gertrude C. Schwebell, illustrated by Eros Keith, and was published by Simon and Schuster, New York, ISBN 9780671651602: I see there are a number of copies available inexpensively online, here for instance. Project Gutenberg has three earlier, less cut translations available for free download, and I'm glad to see scores of people have been getting them recently.)

Undine was set as an opera almost immediately on its appearance, by E.T.A. Hoffmann; thirty years later by Albert Lortzing; then quickly by the Russian composer Alexi Lvov (1846), followed by Tchaikovsky (1869). Nor was Dvořák's the last musical treatment: Hans Werner Henze composed music for a ballet with choreography by Frederick Ashton, first produced in 1958 by the Royal Ballet, with Margot Fonteyn in the title role. (The score was recorded in the 1990s with Oliver Knussen conducting; I'd like to hear it.) And I remember being fascinated by the inscrutably expressive sounds of Akira Miyoshi's radio opera on Ondine, composed in 1959, produced in Italy that year, winner of the Prix Italia in 1960, and issued on Time Records not long afterward.

Undine, to revert to the German spelling, is what seems to be called these days, often dismissively, a "fairy tale." The genre has dropped out of favor, replaced by science-fiction often set in a future, or "fantasy" set in some unspecified present. As it developed as folk literature, though, such tales performed an important function, I think. They are often cautionary, reminding the listener — not always a child, by the way — of the truth and certainty of proper forms of address humans should take toward Nature, toward essentials, toward limits on human ambition, social or individual.

In this particular story a knight-errant falls in love with the adopted daughter of a poor woodcutter and his wife. She turns out to be an Ondine, of course, a water-nymph, who miraculously appeared to the couple soon after the accidental and mysterious drowning of their own daughter. He takes her to his castle, ignoring his already arranged impending wedding to another (foreign) princess. Ondine, in assuming mortality in order to marry, guarantees the tragic outcome.

The rusalka is the Slavic form of the naiad; other forms are called, by their various communities, nixies, or sirens. The Italian willii are similar: the restless ghosts of women who have died of a broken heart, usually on the doorstep of the church when their groom has failed to turn up. From them, the expression: they give me the willies.

The Greeks were right, I think, to believe there were underground streams connecting, for example, the fountain of Arethusa in Sicily (at water's edge, in Siracusa), with an ultimate source somewhere in the Peloponnese. La Motte Fouqué's Undine travels easily between the pool of Dvořák's first act to the fountain of his second, presumably by swimming along one of these underground streams. The English painter John William Waterhouse, perhaps inspired (or cursed!) by his surname, painted at least two versions of a similar naiad, in similar settings.

|

|---|

| John William Waterhouse: A Naiad or Hylas with a Nymph (1893) |

1 comment:

I went to a movie broadcast of a couple of operas and was so horrified by the sound after the luxury of listening to opera live at the San Francisco Opera House for decades that I vowed Never Again.

"Rusalka" is a great opera and I'm glad it's finally making its way into the worldwide repertory at long last. And it is partly thanks to the wildly upsurging reputation of Janacek, which has forced singers to learn Czech, that has made this come about, I think.

Post a Comment