| •Charles Shere: Requiem with Oboe. Healdsburg: Ear Press, 2014 Full study score, 6x9, 48 pages Available at Lulu.com, $9.99 |

I composed the music in 1985, shortly after the death of my mother, just short of her seventy-fifth birthday. You see her there at the left, probably about eight years old, one sock up, the other down, in an old snapshot taken I suppose in Shanghai where she spent her first twelve years, the third of nine children born to a high-school teacher from Sonoma county, in China to avoid a mother-in-law who was apparently giving him trouble. (The family returned to Berkeley as soon as she died.)

My mother admitted freely that she had a tin ear, and I never heard her play the violin, or any other instrument. Or sing, now that I think about it. She recited poetry, sometimes in German, but she was not what you'd call musical. My father was: though he never finished grammar school, he was an intelligent man and a constant reader, and fond of singing, and could play any instrument put in his hands (though I never put a bowed instrument there). But my mother, no.

In her middle years, when she'd returned to college to get a teaching credential, she most improbably signed up for a music-appreciation course. She had her own way of memorizing themes she was supposed to recognize at exam time: I remember her chanting

see the hor-ses run-ning up and down and up… and… downto a frisky tune in Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, for example. But she never really cottoned to the standard repertory. I can't recall her ever going to a concert. Dad did, once, when I was sick in bed, and couldn't get to a performance of the Santa Rosa Symphony; for some reason he went in my stead, and found it lengthy but occasionally rousing, and even brought me the program, autographed by the night's soloist; who, I don't recall. But my mother, no: she wasn't interested.

The only music I ever heard her approve was, for some reason, Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire. I had an ancient recording, conducted by the composer himself, with Erica Stiedry-Wagner sprechtstimming the solo part, and she used to listen to it every now and then, with a determined look in her eye. She said she liked it because it didn't fight with itself, by which I think she meant the lines were clear. I wonder how many of the lay public would have agreed with her. I never thought to ask precisely what it was in the piece that interested her: now that I think about it, it may have been the poetry, written originally in French, translated for Schoenberg's purpose into German — both languages she'd studied, how thoroughly I never really knew, in school, in China.

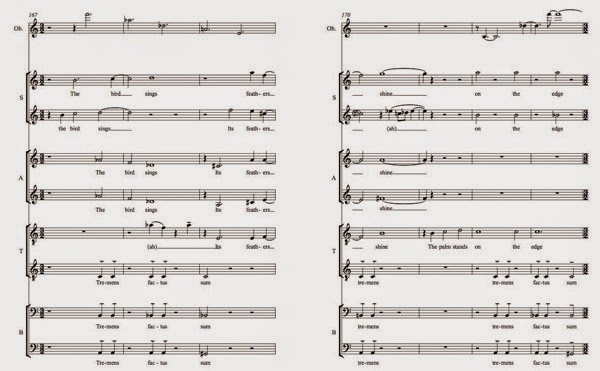

At any rate, my Requiem. It was commissioned (though no money ever changed hands — a common procedure in those days, at least in my experience) by Christopher Fulkerson, a composer of determinedly modernist bent himself, for his chamber chorus Ariel. This was a vocal octet, the conventional SSAATTBB configuration, but comprising eight very good singers with experience with modernist music, good ears, quite clear diction, and supple phrasing. Chris was a good conductor, too, shaping the lines well, maintaining the pitch, balancing the dynamics, bringing out the poetic heart of the texts.

(A few months earlier, Chris had been instrumental — vocal, I mean — well, no, he didn't talk all that much, he was in fact instrumental — in the production of about a third of my Duchamp opera, at Mills College: he found and rehearsed the chorus, some of whom came from Ariel, and took a solo line himself, very nicely.)

Chris had asked for a piece for a cappella voices, but for some reason I wanted to add the oboe. I wanted an aural emblem of a creature from another dimension, to bring the listener out of the contemplation of dying that any Requiem necessarily involves, and take the listener instead to a dimension we do not yet know, and an oboe in its highest register seemed appropriate.

Nor did I set all the usual text of the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. The scary Dies Irae has become a cliché, and anyway death doesn't seem scary to me, in any case shouldn't be dwelled on, I think, as a thing to fear, since after all it is inevitable. And of course the parts about a personal savior don't comply with my own view of things, so I couldn't represent myself as agreeing with certain other components of the Ordinary.

For those parts I substituted two poems by a favorite of mine, Wallace Stevens, who I had reason to believe my mother had also liked, though like so much else his poetry was something we'd never talked about. Not Ideas About the Thing but the Thing Itself, with its window on "a new knowledge of reality," gave me a chance to introduce the high keening oboe, and "Of Mere Being," whose "palm at the end of the mind" seemed to promise a symbolic destination of sorts, provide me, at any rate, with a more spiritual, less sentimental, unearthly alternative to conventional ideas of afterlife.

I wasn't around for the rehearsals of the Requiem: as I recall, I first heard it at its premiere, oddly given in the old Vorpal Gallery in San Francisco's North Beach. I thought it went pretty well. I wish I had a better recording of it: the voices in the live recording made, I don't know whether at rehearsal or performance, seem a little off-mike.

I don't have a program of that performance, and I don't know who the eight singers were — a pity. The high soprano, whose coloratura takes her up to a high E, was really spectacular; the two basses were properly sepulchral; everyone in between negotiated the lines splendidly. And Marilyn Coyne — the one name I do know, apart from Chris Fulkerson's — handled a difficult oboe part with grace, drama, and total musicality.

And, while I agree with the painter Jack Jefferson, who told me once, about reviews, that if you agree with the good ones you've got to buy the bad ones too, I can't help liking the review that showed up a couple of days later in the newspaper:

You can get a copy of the score from Lulu.com for a measly ten dollars plus postage. (Of course the postage is a little exorbitant: be careful the sale site doesn't default to a next-day delivery!) I think you might even be able to download the score as an e-book, though I'm not sure about that. If you don't read music, buy a copy for your local library. If you sing in a chorus, or know someone who does, give it a look. It's not my favorite of my pieces, but I like it. I wouldn't mind hearing it again, maybe even sung by a full chorus. Besides, I've been thinking a lot about my mother lately…A Program of Modern Works By the Ariel Choral Group

... The night's outstanding item was the premiere of Charles Shere’s moving “Requiem With Oboe” (1985). ...

Shere’s Requiem both uses and shuns the traditional Latin text. Two of its four sections use the Roman Catholic liturgy — “Requiem aeterna” and “Hostias et preces.” But the larger part of the work employs two Wallace Stevens poems: “Not Ideas About the Thing, but the Thing Itself” and “Of Mere Being.”

Shere’s Requiem begins with a trope, “Requiem (mater) aeternam” — “mater” being an insert. Bits of the Latin text turn up briefly within the Stevens poems as well. To all this, Shere added snippets of oboe solos (played by Marilyn Coyne — mostly in the high register) as a kind of genteel wailing (the piece is dedicated to his late mother).

Shere set all this in a devoutly simple style. The idiom strongly leans on 14th and 15th century principles of counterpoint. What is heard is something of the motet manner, only updated into a freely atonal idiom.

What emerged was a softly lamenting cantata, liberated from violence or threats. There is, for instance, no hint of the Last Judgment. Shere has produced a work of tenderness roughly comparable to the Faure Requiem in mood.— Heuwell Tircuit, San Francisco Chronicle

Technorati Tags: My music

1 comment:

Charles, your music and your words will continue to flow into the ether and thence into the human brain. I'm convinced that our efforts will survive somehow; so was Charles Olsen ("Projective Verse") : "A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it . . . , by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader."

Post a Comment