Fisk Mill Cove, Sonoma coast |

SATURDAY,

SATURDAY, J

UNE 2: GLORIOUS weather, fine terrain, good company — only the pace, a little slow and far too often halted, detracted from a first-rate long day's walk.

The event was planned and organized, admirably, by Jeff Tobes, who has led similar history-oriented group walks on a number of previous occasions. This was in fact the eighth annual 25-mile walk produced for the Sonoma County Historical Society, and Jeff got more than he'd bargained for this time, as 130 people eventually signed up for the day.

Most of the walkers boarded big yellow school buses in Santa Rosa, but Thérèse and I opted for the closer departure point in Forestville. This allowed me to get up at 3:15 am rather than 2:30. I can't recall when I've got out of bed so early in the morning: but we were rewarded by a rare sight, the almost full moon about to set, huge and eerily apricot-colored, in an otherwise pitch-black sky.

About quarter past four the bus arrived for us. It took us out River Road, through Guerneville and Monte Rio and Jenner, then up Highway 1, Meyers Grade Road, and Seaview Road to the parking lot at Fort Ross School — about thirty miles from Forestville, but a slow slow grind; some of the roads were hardly wide enough for the bus, and the turns were tight, the drop-offs scary.

We arrived at the parking lot, still dark, about five-thirty, grouped for a count and instructions, did a few stretching exercises, and waited for our six o'clock departure time. I suddenly realized I'd forgotten to wear a hat: at 3:30 am, a hat was the last thing in my mind, and I'd neglected to set it out with my pack the night before. Oh well: I've done without before.

We set off almost on schedule just a few minutes past six, daylight by now well on the way. The morning sun was glorious through the tall firs and redwoods, and we walked past a few dooryards surprisingly tucked behind fences — you never realize how many people live out here in so apparently remote a place.

When I was in high school, in the early 1950s, the few students whose families lived out here usually boarded in town — Sebastopol — during the winter months. My mother taught a few years at Fort Ross school, and after only a few weeks realized she'd have to live out near the school; the commute from Hessel, 45 miles away, would take a good two hours in fair weather, much longer in heavy fog or rain. (She always had a chain saw and a shovel in the car.)

We walked three and a half miles up Seaview Road, then turned onto Kruse Ranch Road for another half mile, to Plantation. I knew this from the old days; Mom and my two youngest brothers lived here for a few months — I think they were boarded by school families by turns during her tenure: Fort Ross School, Plantation, Salt Point, Timber Cove. (Finally she found a place of her own, near the north end of the bridge over the mouth of the Russian River near Jenner, in a little two-room shack that disappeared long ago.)

In those days Plantation was a rather run-down boarding school run by the Crittendon family. Now it's a much more polished looking

farm camp; I can imagine it would make a fine summer experience for kids needing to learn the basic skills of hard work and healthy living.

The sun was slanting down brightly over the gleaming white dormers of the main house, and we all gathered around outside the restored Druids Hall, where volunteers cooked a welcome breakfast for us — scrambled eggs and bacon, beans, rice and salsa, tortillas, and cases of fresh peaches and strawberries; best of all, plenty of good hot coffee — and, of course, the possibility of a pit stop.

I was impressed with Plantation. Improbable as it seems, it was a working resort a century or so ago; people rode up on stage coaches. By 1871 there was a saloon and a stage house nere and that same year a school was organized. The Druids Hall went up in the late 1870s — people needed their society in those days — and a post office followed at the turn of the century.

After half an hour or so we resumed the walk, continuing on Kruse Ranch Road, then on narrow trails through fairly dense forest in Kruse Rhododendron State Natural Reserve, where the native rhododendrons, lanky and a bit past their peak, still showed blue and purple high among firs and redwoods.

In the understory, at our feet at the edge of road and trail, among the ferns, we saw lilies, orchids, iris, and a number of other flowers — Khloris knows I am no botanical expert; I'm content to enjoy the imponderable generosity of their mere flowering existence.

By now, of course, we were descending at a pretty good clip; Plantation was about a thousand feet above sea level; we were headed for the coast. (Our starting point at Fort Ross School was the highest point of the day, at 1285 feet.)

In the dense forest my trail-mapping app lost sight of the GPS satellites it needs, but on a walk this long I think the resulting margin of error is acceptable. (You can download the .kmz file of waypoints for the entire walk

from my website.)

After about three hours' walking, not including the breakfast break, we hit sea level at Stump Beach, downcoast from Fisk Mill Cove, which looked to me like about the one-third point on the walk. This part of the northern Sonoma coast, from Jenner at the mouth of the Russian River up to Sea Ranch or so, is studded with coves, most of which were used for loading lumber onto schooners in the sixty years or so after the Gold Rush.

Fisk Mill Cove, Gerstle Cove, Ocean Cove, Stillwater Cove, Timber Cove: we skirted all of these, sometimes on trails in parks, sometimes bushwhacking across fields, a couple of times marching three or four abreast in one lane of Highway 1, when twice it was restricted to one-way car traffic just to accommodate us.

The flowers were truly extraordinary. Reds, orange, yellows, blues, most of the blooms quite small of course — these plants have to be thrifty on their windswept, salt-sprayed bluffs. At times we came to groves of low mounding beach cypress; our trail even entered these mounds at times, and we found ourselves in dark, fragrant caves.

At Gerstle Cove we headed inland, climbing through fairly thick forest to cross the highway and head for the picnic grounds at Woodside Campgrounds in Salt Point State Park. Sadly, because of the California state deficit, many of the state park facilities are closed; but these campgrounds are operating — though curiously empty at the moment. The Fort Ross Store provided sandwiches, milk, and juice, and we sat at a picnic table, Thérèse and I and an interesting woman who joined us.

photo: Thérèse Shere |

Among these 130 people there were few solitaries. Most seemed to be in pairs, some in larger groups, families perhaps, or walking buddies. Most seemed pretty well geared, many with hiking sticks and backpack-canteens; and though Jeff had cautioned us against carrying backpacks — and offered "sag wagons," cars that convoyed along and met us at strategic locations, to carry any packs, coats, extra shoes and the like for us, still nearly everyone had a day pack or a fanny pack or something of the sort. (I wore my hiking bandolier, which carries a one-liter water bottle, my iPhone and a couple of external batteries, a handful or two of dried figs and another handful or two of salted nuts, a notebook, sunglasses, and the like.)

By now it was past two o'clock, and I began to wonder how we'd ever manage to arrive at Fort Ross by six. We headed back to the coast, skirting Ocean Cove by walking on the highway for a quarter-mile or so, then returning to the trail along the edge of the bluff, southeasterly to Stillwater Cove. Here we took a detour up the Stillwater Ranch driveway, past its handsome stone house and its annoying peacock, and into Stillwater Park, one of Sonoma County's regional parks, where I was surprised to find the one-room Fort Ross schoolhouse — so surprised that I didn't think to photograph it, even though it was the building my mother taught in half a century ago — before it was declared surplus property, given to the state, then abandoned to the county's care, occasioning its relocation in this historically irrelevant place.

Oh well. From Stillwater we head westerly, away from the coast, up a pretty steep trail and through a private homeowners' association reserve — the sort of thing that can only be done by special permission, one of the reasons it made sense to walk in this group. This being the county historical society, and our leader being a retired history teacher, we took a short detour to ring a historical bell.

Before long we reached Timber Cove Road, whose quite steep, dead straight descent south to the coast was probably my least favorite part of the walk. Downhill on asphalt, after twelve or fifteen miles on the trail, is hard on toes and calves. We kept to the soft edge alongside the road where possible, but it was pretty narrow.

But soon enough we were at Timber Cove. I stepped into the Timber Cove Inn and phoned home to arrange for a pickup at Fort Ross, as we'd decided not to ride the bus back — it was going back via our start-point at Fort Ross School, and would take a long time, on twisty roads in the dark, right after dinner: not an attractive prospect.

The other 129 walkers were out in the parking lot, where the sag wagons and the trailer with its two portable toilets were steadying the troops. We were within shouting distance, only three miles or so, of our destination. But first our leader wanted to show us Beniamino Bufano's

Madonna of the Expanding Universe, a 93-foot obelisk in the sculptor's characteristic naive-deco style which often strikes me as simple-minded, but occasionally attains considerable strength.

This particular piece, probably unfinished, takes a lot of thought if it isn't to be dismissed (or for that matter accepted) too glibly. There's no denying its seriousness of intent, and any work of art with so much thought, work, and intention behind its creation deserves reflective appreciation.

I won't describe it; you can read about it

here. You must know, though, that it is the property of the State, and placed in a state park, the second-smallest in California — just big enough, we were told in an interesting and very enthusiastic little lecture by the park ranger, to contain it should it topple, which Poseidon forbid.

(The smallest state park contains Simon Rodia's Watts Towers, in Los Angeles: the two parks, and the two works of art they contain, make an interesting symmetry: the product of compulsive idealist outsider artists during the peak of Modernism, with foreshadowings, ironically, of the most intellectual conceptual art that would seem to displace them utterly in the history of 20th century art.)

We single-filed away from the

Madonna on what struck me the most dangerous part of the walk, a dozen feet on a tight path that skirted a drop of fifty feet or so to the rocks below. At one point I stumbled on my own shoe and caught hold a branch hanging over the void: it would never have held me, but it steadied me, and I didn't attract any attention that I noticed…

After a half-mile or so on the highway, again protected by flashing red lights at each end of the stretch, we turned once again toward the coast, walking through first a private campground, then someone's side yard — amazing, that people can privately own territory at the very edge of the continent. We stepped through a private gate, walked through another enchanting field of flowers, and then surprisingly trod a hundred feet or so of ice plant, the succulent leaves breaking and weeping underfoot.

Another grove of cypress, another stretch of roadside trail, and then we came to a board gate at a fence. In a ludicrously clumsy ballet 130 of us laboriously hauled ourselves over the boards, our toilet-truck standing by in case of emergency I suppose; and then we set out again through a long final field, some of the most difficult footing of the day, a cow-pasture full of gopher holes, molehills, and hidden pools and runnels. This led to a second set of board gates, and here I actually had the sense, after watching a few people climb over them, to find the sliding bolt, draw it back, and open the gate for the others. (Of course, not being that smart, I'd already laboriously climbed it myself.)

photo: Thérèse Shere |

By now the light was changing; the wind had come up; we were all ready to end the walk — and the fort still lay a mile or so off. All discipline was gone, 130 walkers were scattered across the cow-pasture, many toiling along a track, others of us heading on our own ideas of a more direct route to where we thought the fort must lie, teasingly out of view.

And then there we were. An asphalt road led underneath an overhanging cypress; beyond, the school buses were parked, and the sag wagons, and there was fragrant smoke in the air. We walked past the Call house, then through the stockade gate. I hadn't been here in years, not since the last big earthquake caused a lot of damage, and Highway 1 was routed away from the site, and the old Russian church was restored, and more recently a replica was built of the imposing Magazine, which I hadn't known about at all.

photo: Thérèse Shere |

Another crew of volunteers were cooking up rice, beans and chicken in huge iron pots over an open fire. There was an array of what I think of as Oklahoma funeral salads: potato salads, macaroni salads, olive-and-sweet pepper salads. The rolls had been donated by Franco American, and took me back sixty-five years when they were a family favorite in my childhood; and the butter was churned on the spot from cream donated by neighboring milk-cows. Plenty of coffee; plenty of fresh fruit; delicious Russian cookies. It was cold, an hour and a half later than we'd planned, and we hunched over our plates.

Then came our reward: a quick lecture on the history of the site, and a cannon salute. Walkers volunteered for the five-man crew:

Tent the vent! Clear the piece! Fire in the hole! Our leader set a match to the fuse; we covered our ears; a fine loud satisfying

POP! roared across the champs-de-Mars, and our day was over.

It was

l'heure bleue, and the full moon had climbed to the tip of a windblown cypress east of the stockade. Lindsey was waiting for us in the parking lot, we thought; soon I'd be home, perhaps with a celebratory Martini.

Of course it wasn't quite so simple. Unsure of our exact location, and concerned that we hadn't shown up in the parking lot, she'd driven off — to Fort Ross School; to Plantation; to Timber Cove, where she messaged me. Alas, there is virtually no cell phone coverage out on that coast. Ultimately we found one another, of course, after we'd walked another mile or two between parking lot and stockade. A long day; a strange day; a tiring day; a glorious day. I realize, just now, typing these words, I'd do it again.

WHEN WE BOUGHT our place here on Eastside Road, hence the name of this blog, we found twenty-eight acres, a horse, three sheep, a blue two-storey house built in 1872 by Lindsey Carson (Kit Carson's brother, an itinerant carpenter who seems to have built the same house on a number of Sonoma county locations), two and a half barns, an oil shed, a machine shed, a chicken house, and a long-since disused outhouse.

WHEN WE BOUGHT our place here on Eastside Road, hence the name of this blog, we found twenty-eight acres, a horse, three sheep, a blue two-storey house built in 1872 by Lindsey Carson (Kit Carson's brother, an itinerant carpenter who seems to have built the same house on a number of Sonoma county locations), two and a half barns, an oil shed, a machine shed, a chicken house, and a long-since disused outhouse. AND NOW, MARVELOUS how much time is gained on fast days,

AND NOW, MARVELOUS how much time is gained on fast days,  SOME LITTLE WHILE ago, in July 2007, I wrote

SOME LITTLE WHILE ago, in July 2007, I wrote

SATURDAY, JUNE 2: GLORIOUS weather, fine terrain, good company — only the pace, a little slow and far too often halted, detracted from a first-rate long day's walk.

SATURDAY, JUNE 2: GLORIOUS weather, fine terrain, good company — only the pace, a little slow and far too often halted, detracted from a first-rate long day's walk. About quarter past four the bus arrived for us. It took us out River Road, through Guerneville and Monte Rio and Jenner, then up Highway 1, Meyers Grade Road, and Seaview Road to the parking lot at Fort Ross School — about thirty miles from Forestville, but a slow slow grind; some of the roads were hardly wide enough for the bus, and the turns were tight, the drop-offs scary.

About quarter past four the bus arrived for us. It took us out River Road, through Guerneville and Monte Rio and Jenner, then up Highway 1, Meyers Grade Road, and Seaview Road to the parking lot at Fort Ross School — about thirty miles from Forestville, but a slow slow grind; some of the roads were hardly wide enough for the bus, and the turns were tight, the drop-offs scary. We set off almost on schedule just a few minutes past six, daylight by now well on the way. The morning sun was glorious through the tall firs and redwoods, and we walked past a few dooryards surprisingly tucked behind fences — you never realize how many people live out here in so apparently remote a place.

We set off almost on schedule just a few minutes past six, daylight by now well on the way. The morning sun was glorious through the tall firs and redwoods, and we walked past a few dooryards surprisingly tucked behind fences — you never realize how many people live out here in so apparently remote a place.

In the understory, at our feet at the edge of road and trail, among the ferns, we saw lilies, orchids, iris, and a number of other flowers — Khloris knows I am no botanical expert; I'm content to enjoy the imponderable generosity of their mere flowering existence.

In the understory, at our feet at the edge of road and trail, among the ferns, we saw lilies, orchids, iris, and a number of other flowers — Khloris knows I am no botanical expert; I'm content to enjoy the imponderable generosity of their mere flowering existence.  Fisk Mill Cove, Gerstle Cove, Ocean Cove, Stillwater Cove, Timber Cove: we skirted all of these, sometimes on trails in parks, sometimes bushwhacking across fields, a couple of times marching three or four abreast in one lane of Highway 1, when twice it was restricted to one-way car traffic just to accommodate us.

Fisk Mill Cove, Gerstle Cove, Ocean Cove, Stillwater Cove, Timber Cove: we skirted all of these, sometimes on trails in parks, sometimes bushwhacking across fields, a couple of times marching three or four abreast in one lane of Highway 1, when twice it was restricted to one-way car traffic just to accommodate us.

After a half-mile or so on the highway, again protected by flashing red lights at each end of the stretch, we turned once again toward the coast, walking through first a private campground, then someone's side yard — amazing, that people can privately own territory at the very edge of the continent. We stepped through a private gate, walked through another enchanting field of flowers, and then surprisingly trod a hundred feet or so of ice plant, the succulent leaves breaking and weeping underfoot.

After a half-mile or so on the highway, again protected by flashing red lights at each end of the stretch, we turned once again toward the coast, walking through first a private campground, then someone's side yard — amazing, that people can privately own territory at the very edge of the continent. We stepped through a private gate, walked through another enchanting field of flowers, and then surprisingly trod a hundred feet or so of ice plant, the succulent leaves breaking and weeping underfoot.

There's so much to see on a walk like this; so much to wonder about. What's that wildflower, for example, that sports both yellow and orange blossoms on a single plant? The leaves suggest some kind of pea, but what is it?

There's so much to see on a walk like this; so much to wonder about. What's that wildflower, for example, that sports both yellow and orange blossoms on a single plant? The leaves suggest some kind of pea, but what is it?

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this?

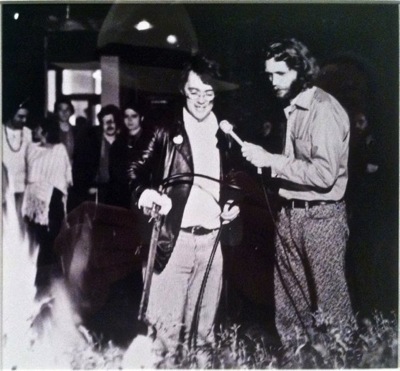

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this? Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.

Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.