Bride concerto

HERE WE ARE again, revisiting old work instead of doing new work. I think it's one of the great drawbacks of technological improvements: the greatly enhanced ability to revisit, review, revise, Lou Harrison's motto was

Cherish. Consider. Conserve. Create. Mine seems to have devolved to

Revist. Review. Reconsider. Revise. The project at hand is honorable, though, because it's attached to an event by its very nature retrospective: the Duchamp show in Healdsburg at the

Slaughterhouse Space. This installation, which closes November 7, gathers visual work by XXX artists — painting, sculpture, video, installation — in the haunting and endlessly beautiful atmosphere of a former slaughterhouse. (These four photos give only a rough idea of the space.) Recorded music from or associated with my Duchamp opera runs continuously as you investigate the exhibition.

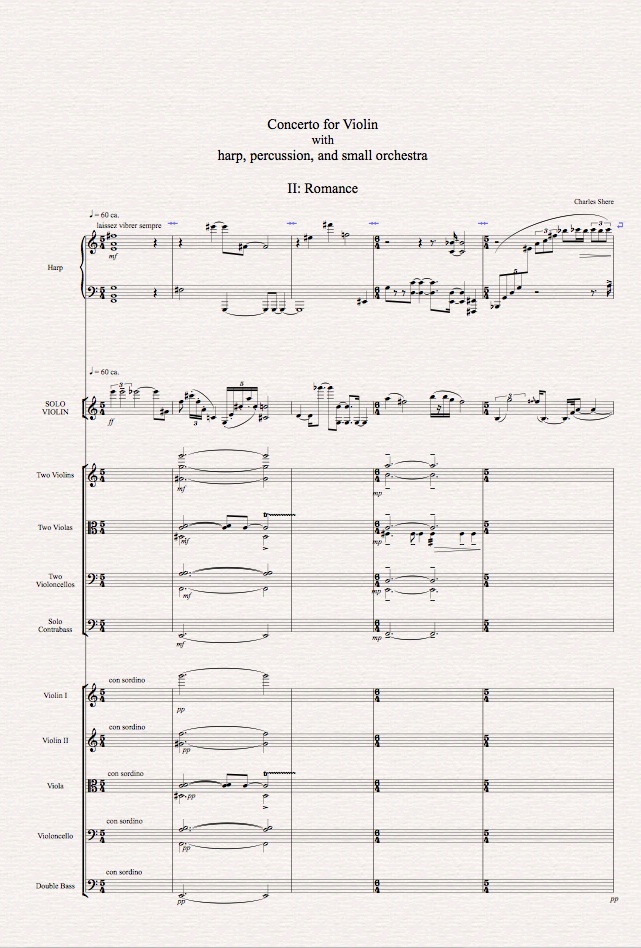

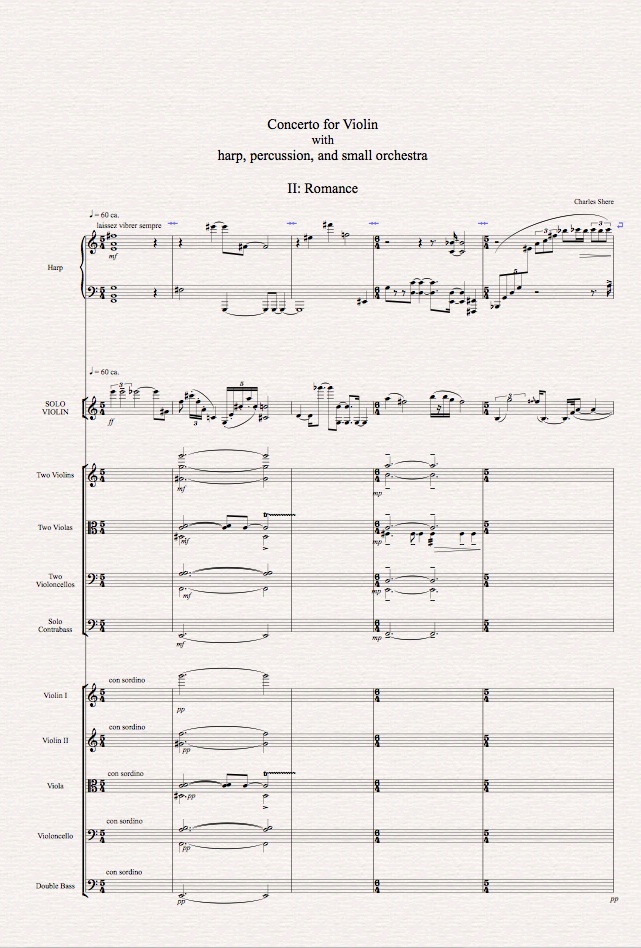

Among the events associated with the exhibition is a short talk I'll be giving next week, describing the translation of Duchamp's painting to the rather different medium of staged opera. I've written about this before on this blog; today, since I just finished re-notating its first movement, I'll introduce you to my concerto for violin with harp, percussion, and small orchestra, one of two solo concerti concealed within the long fourth scene of the second act of the opera. There a solo piano often represents the Bachelors; the violin represents the Bride. Both have prominent roles in a Ballet with chorus and vocal soloists in that scene, and much of the music can be extracted, stripped of its vocal material, and performed as purely instrumental works. The piano concerto has yet to be realized, though a version of it has appeared as a solo work, the

Sonata: Bachelor Machine of 1989.

For that matter the Violin Concerto has not yet been fully realized, even though it, like the rest of this long scene, was completed in 1985: the opening movement, which contains a number of passages written in non-standard “graphic” notation, has yet to be transcribed and performed. In 1989 I extracted the second, third, and fourth movements of the concerto for the Cabrillo Music Festival, where it was performed on a concert of works in progress. I was told the Concerto was particularly interesting to the program committee because of its many silences and light texture, and there was some dismay when I mentioned that I hadn’t yet finished putting notes in.

One small joke in the score is its snare drum: the part was lifted literally, and without permission, from Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra (1959). After the concert, when I asked what he thought of my concerto, he suggested that I transpose the whole thing up an octave. When I told him that I’d lifted his snare drum part, he suggested that I should have taken the solo violin part.

There remains the question of what this Violin Concerto is “about.” Beni Shinohara, who played the piece beautifully, asked that very question while the piece was in rehearsal, and I told her about one of the underlying themes of Duchamp’s painting — its ironic erotic atmosphere, in which the Bride, always swaying out of the Bachelors’ reach, remains in a constant state of unrelieved excitement. “I thought it was something like that,” Beni replied, and played it beautifully.

I've entered these notes, a snapshot of the opening measures of the score, a .pdf of the Romance which served as the opening movement, and an .mp3 of the opening of the performance of that movement on my

website.

3 comments:

Reading your comments, here, I'm reminded of the debate which once raged regarding the tension between "programmatic" and "pure" music in the musical quarterlies.

Regarding music and time: I'm not sure Duchamp's notions of accident and chance can be very successfully imported into musical expression, since the "evidence" of the accident occurs only for the duration of the playing, and can't be studied the way a physical object can be (except through awkward means--studying a score, playing a "reduction" etc). What is an accident in sound--like hearing a car horn that sounds like Prokofiev--may have a literal relationship only by virtue of the coincidence of instrumental ranges/pitches. "Listening" through the available generators of traditional sound may seem narrow and too discrete, but otherwise sound is just the chaotic occurrence of use, or the residue of physical events (engines and birdsong). An enigma.

Hmmm. Much to think of here. Accident and chance can of course be used in decisions regarding sounds — their origins, their dimensions (pitch, duration, loudness, etc.), their distribution within a piece of music. That’s been standard operating procedure for half a century.

Some of us think all significant aspects of music occur “only for the duration of the playing.” That said, for many of us, score study and reduction performance ere not particularly awkward; they’re reliable and productive tools in the job of “learning” pieces of music.

Your comment suggests a deeper subject, particularly when I return to your opening paragraph: the nature of “program” in the writing, playing, or hearing of music. I think program is present very much more often than purists realize. Leonard Ratner wrote a very interesting book (Classic Music: Expression, Form and Style; MacMillan Publishing Company, 1985) discussing this (among other things); much music commonly thought to be “abstract” had in fact rhetorical “meaning” to the audiences who knew the “language.”

Most of us have lost that language, and can no longer listen to traditional music for its intended affect. Mozart and Beethoven are no more “understood” by the average concertgoer than are Cage and Stockhausen; it’s only the familiarity of their music that’s known, not its “meaning.”

There’s a lot to be written, said, and thought about in the subject of musical “meaning,” and I think accident and chance — and understanding and, more to the point, more poignant and delightful: misunderstanding — cannot be considered apart from the context of musical “meaning.” But this is resistant, and I’ve got work to do.

I think 19th Century composers like Liszt, were almost writing topical "essays" on current events. A symphony following a big conflict, for instance, was like an allegorical narrative epic by a poet (like Byron).

What those "essays" actually said, however, is open to interpretation. Elegy is perhaps the easiest, like Tennyson's In Memoriam, compared to Chopin's death march. Janacek's 1.X. 1905.

Post a Comment