|

| The view out our window, Gasthaus Borealis |

And I think I have been enchanted by Rovaniemi. We spent only three days there, and two nights, and we left three days ago now, but it seems more present in my mind than does Helsinki, which is not exactly short of impressions itself.

Rovaniemi is the capital city of Lapland — the northern half of Finland — with a population of about sixty thousand. About six miles south of the Arctic Circle, it's a bit of a tourist destination even in the winter: it's near Santa Claus Village, which didn't interest us; and it offers viewings of the Aurora Borealis, which did.

Or it should offer such viewings. In fact the town is very brightly lit, and our only serious attempt, walking about in -20° (Celsius: -4° Farenheit) weather for an hour or so, in relative dark, on snow and ice, turned up nothing but a frozen nose.

|

|

|

|

|

But there were compensations. For one, the museum Arktikum, where this aerial photo of reindeer on the move suggested to me a completely different way of looking at, for example, cave paintings of groupings of animals. Distortion, gathering, orientation, direction — and recalling that the climate of the cave painters was very different from ours, and was undoubtedly glacial-marginal…

You can think about such things forever; there are so many things to see and to think about. The white canvas of the snow helps this, of course, bringing color out more vividly. More to the point, the snow covers all kinds of visual distractions. You can't tell the sidewalk from the street. And there is much less traffic outside; hardly anyone on the sidewalks; very few cars, and they slow.

Then there's the effect of the short day. We knew all about this, of course, intellectually, but it's another thing to experience it actually. Daylight begins to take hold at ten in the morning; by two-thirty it's definitely fading. In compensation, the twilight hours are long, and the darkness itself is bluer than black, and offset by the nearly full moon and the reflective white of all that snow.

Of course we only experienced three of those short days, though the last week had gradually got us used to the idea as we settled in Stockholm, then moved our way over two or three days toward the north end of the Gulf of Bothnia. I'd love to spend a couple of solid weeks here, preferably when the moon is dark, to get a better idea of it; and I regret that Rovaniemi is so much lit, though I understand the desire of its citizens to do so.

I'd like, too, to spend a few weeks this far north in the summer, though I imagine that would be more fatiguing for lack of sleep. The point is, I can't really begin to imagine how formative the radical swings in daylight length are among the influences on the arctic mentality. To what extent does it encourage a desire for sociability, for example; to what extent does it produce a pragmatic kind of fatalism, a sense of human vulnerability in the face of natural elements.

Arktikum is a very impressive museum, with a wide variety of material, whose curatorial presentation encourages this kind of contemplation. The main hall combined artifacts and reconstructions, two- and three-dimensional exhibits, and explanatory panels (in English, thankfully, as well as Finnish) to present a fine introduction to the Arctic life. It included nature, with stuffed bears and muskrats and these three swans flying overhead; and climatology, with clear explanations of the patterns of wind, temperature variation, and daylight; and botany; and anthropology.

The latter included what seemed to me a thorough and very sympathetic overview of the Sami, the indigenous migratory people we used to call Lapps, for centuries reindeer herders but now mostly apparently settled into residential communities of various kinds. We were told later on, in Helsinki, rather dismissively, that only perhaps ten percent of the Sami still herd reindeer, and they do that using helicopters; that there hasn't been an undomesticated reindeer for over a century; that the Sami now live mostly on the dole or by producing handicrafts. I'm sure this is all true from the perspective of the person who was explaining it all to us; but I doubt it is true from the Sami point of view, and I can only reserve my judgment.

As I say, the Arktikum presentation was sympathetic, reconstructing the Sami way of life before "civilization" began to settle the extreme North but also following them into the present. One affecting diorama, for example, showed a meeting of three or four apparently unemployed men in a rural gas station-cafe; they could have been in Nevada or Wyoming.

Another presented the life and career of an itinerant photographer, Valto Pernu (1909-1986), the last market photographer in Finland, who traveled with a wagon studio and a big camera of his own making for years before settling in Rovaniemi for his last twenty years, still photographing in the summertime in a studio tent.

We were dumbstruck confronting one portrait he'd made, I suppose in the 1930s, of an adolescent boy in a visored cap reseting on his bicycle in front of a cabin. He looked exactly like me at sixteen. I know my haplogroup (I-M253) represents peoples who migrated out of Africa eventually through Hungary to northern Europe, with a particular concentration in Scandinavia, so perhaps the proud, sober, rather grumpy teenager posing somewhat self-consciously on his bicycle really is me in an alternative universe; the light, cold, and hours here encourage this kind of thinking.

There's also a quite scientific component of exhibits in the museum, explaining winds, the earth's tilt, glaciology, and all that sort of thing — including, of course, the Northern Lights, still eluding us. But recently it's human history that's interested me the most, and I wanted to linger longer than we could afford over a temporary exhibit relating to the German occupation of Finland during World War II.

When I was a boy it seemed to me we took a dim view of Finland. World War II was on, and in Berkeley shop windows there were lots of propaganda photos and posters. On the maps, Finland was clarly a part of the Axis — I always confused "axis" and "axle," and wondered at the long stretch of black on the maps indicating the enemy, from Finland on the north south through Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Greece… All those territories were The Enemy, Finland included. It's disturbing that the prejudices formed so long ago, if not confronted and examined, tend to remain influential.

Finland was a part of Sweden from the 12th century until 1809, when it was granted a degree of autonomy as part of the Russian Empire. During the Russian Revolution, in 1917, Finland declared her independence, then plunged into civil war between the leftist "Red" Finns and the German-supported anti-communist "Whites." The war lasted only three months, thanks to the intervention of the German army; but it was brutal, involving murders and starvations and the conscription of boys as young as fourteen.

The new Republic of Finland knew peace only until 1939, when the Soviet Union moved against its southeastern coastal and agricultural land. Three wars followed in quick succession: the Winter War, 1939-40; the Continuation War, with Germany now occupying much of the country and continuing war against the Soviets; then, from 1944 to 1945, the Lapland War, when Finland turned against its former Nazi ally. Enraged, the Germans left nearly total destruction behind their retreat.

Rovaniemi was devastated. Two large relief maps in the Arktikum museum present the city as it was before and after that destruction; the photographs and narrative panels in the temporary exhibition brought more immediate and personal insight to the fury of the betrayed Germans, who during their occupation had grown quite intimate with the Finns.

(Finland was important to the German war effort as a beachhead against the Soviet Union, a supply center for the Norwegian campaign to cut off supplied shipped around the North Cape, and for the supply of minerals and lumber.)

After the final defeat of the Axis in 1945 Finland rebounded rather quickly. Unlike western Europe she did not participate in the Marshall Plan, as she also did not join NATO: proximity to the Soviet Union dictated a prudent course. Likewise, though, apart from severe reparations paid to the USSR, she was not completely dominated by Russian authority.

The Finnish architect Alvar Aalto was commissioned to design the rebuilding of Rovaniemi, and submitted a plan based on the main existing lines: the railroad right-of-way (all rails seem to have been ripped up), the river, and the tracks of the main roads. Taken together and viewed from above these suggested the outline of the head and antlers of a reindeer, symbolically underscoring Rovaniemi's importance to the northern province.

As an administrative and cultural capital for all of Lapland, the city needed major public buildings. Of Aalto's project, three were realized — administrative center, library, and concert hall. But Aalto and his work will be described here another day…

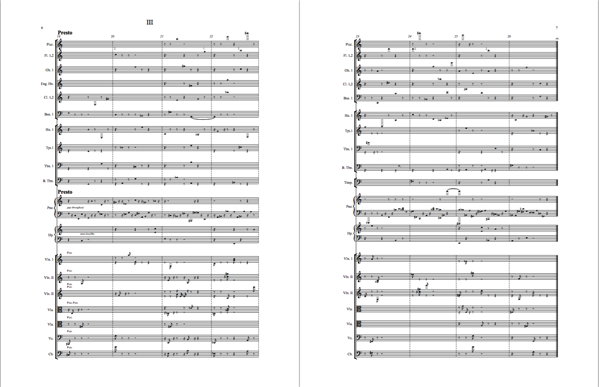

Six systems of music, each but the third lasting about a minute, were conceived as both linear and textural analogues of these threads. The unsynchronized repetitions and reinforcements in the music was meant to represent the variations and displacements of physical bodies caused by gravitational disturbances.

Six systems of music, each but the third lasting about a minute, were conceived as both linear and textural analogues of these threads. The unsynchronized repetitions and reinforcements in the music was meant to represent the variations and displacements of physical bodies caused by gravitational disturbances.

A CORNER OF THE BLEAK Gatchina Palace, outside St. Petersburg, as painted earlier this year by the California artist Inez Storer. And this is just a corner of the painting, too — or, rather, a detail taken from nearly the center of the painting, the entirety of which I'll set at the end of this post.

A CORNER OF THE BLEAK Gatchina Palace, outside St. Petersburg, as painted earlier this year by the California artist Inez Storer. And this is just a corner of the painting, too — or, rather, a detail taken from nearly the center of the painting, the entirety of which I'll set at the end of this post.