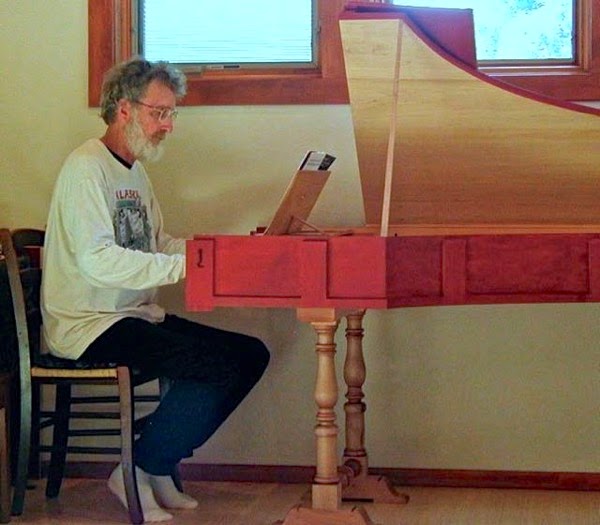

| Bhishma Xenotechnites, August 2010 (photo: Ann Basart, released into the public domain, cc-zero) |

Eastside Road, March 29, 2015—

OVER THE YEARS there have been occasional references on this blog to my reclusive friend to the north. He was so reclusive that I hesitated to mention him by name; he was a man who very much desired his privacy. Yesterday, though, he left us for that ultimate privacy, and today I begin a reminiscence — an informal one, which will likely accumulate in future occasional postings.In the middle 1980sis I wrote a short biographical note on him for The New Grove Dictionary ; I won't reproduce it here for copyright reasons, but here's a trot:

Douglas Leedy: Born Portland, Oregon, March 3, 1938

Studied Pomona College, UC Berkeley (MA 1962)

Played French horn, Oakland Symphony, San Francisco Opera and Ballet orchestras, 1960-65

Traveled in Poland, 1965-66

Designed electronic music studio, taught, and led ensembles, UCLA, 1967-70

1970-80 taught at Reed College, USC, and Centro Simon Bolivar in Caracas

1970s began drawing away from equal temperament, western European romanticism, and Modernism

1979-80 studied with K.V. Narayanaswamy in Madras

1984-85 mus. dir. Portland Baroque Orchestra, Portland Handel Festival

His relocation to his native Oregon — at first in Portland; subsequently Oceanside, Netarts, and finally Corvallis — coincided with a definitive break with Modernism, equal-temperament, and Euro-American politics and economics as they had developed in the years since the early 1960s. For a time he taught at Reed College, in Portland; and he undertook a conducting career, with considerable musical success in the 1985 Handel Festival in Portland. His increasing inability to compromise his ethical and musical standards made performance distasteful, however, and he withdrew from public performance and teaching. It was about then that he put away his birth name, Douglas Leedy, and revealed a new his newly re-integrated persona, Bhishma Xenotechnites. As he described himself, he was "a strictly West Coast, empirical, non-academic musician."

At about the turn of the century he began showing symptoms of a muscle-wasting disease, later diagnosed as Inclusion Body Myositis. By September 2002, when he made his last hike with Terry Riley and me and our wives, he was already walking with difficulty, requiring a cane and unable to negotiate stairs. Increasing frailty did not interfere with his scholarship, but by 2011 or so he was having increasing difficulty playing at the keyboard.

In the first decade of this century he was increasingly drawn to the monuments of archaic and ancient Greek. He argued that the great poets, playwrights and even in early cases the philosophers were in fact composers, in that their work was intended for public sung performance; and he dedicated his final years to a proposed restoration of the sound of this important body of work. Already used to the acquisition of languages — he spoke passable Spanish, French, Polish, German, and Latin — he became a fluent reader of Latin and ancient Greek.

Ultimately the result was a magnum opus of his own, Singing Ancient Greek, which was accepted for peer-review online publication by the University of California Classics department — unprecedentedly, in spite of his having no degrees in Classics. (The book can be read and downloaded here.)

I was fortunate — blessed, even — to have been close to Bhishma over the last dozen years, as the photo above suggests. We made a few trips together: on back roads through California's Coast Range to Parkfield; to the coast and up past Mission San Antonio; through the countryside around Mt. Shasta. Lindsey and I visited him nearly every time we drove through Oregon, two or three times a year. It was alarming to see his increasing frailty, but almost weekly telephone conversations, often of an hour's duration or more (and my friends and family know how I detest telephone conversations), continued to be diverting, instructive, and thought-provoking even in his last days. We talked about the weather, global matters, articles in The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, the poetry of Virgil and Horace, music of course, old times, and last things. He never neglected to ask after my family and those of my friends he had met and had liked.

By the close of 2014 he had grown very frail. He could no longer swallow solid food — and he had always been a gourmet and a gifted cook. He could no longer hold books of more than the smallest dimension, let alone get them down from the shelf. He was falling frequently. Living alone was no longer really possible. I knew that he felt that with Singing Ancient Greek, complete in early 2014, and Monochord Matters, finished late last year, he felt that his work was done. He had no fear of death, and no taste for continued life on the terms he could not change.

On Friday March 13, ten days after his 77th birthday, he entered hospice in an assisted-living facility in Corvallis, taking with him recordings of Stravinsky's Apollon Musagète and Sibelius's Sixth Symphony and one book, "the greatest poet of them all" as he said, Pindar. There he died, on the evening of Saturday, March 28, as he had lived the past thirty years, on his own terms.

Bhishma was, I think, one of the most intelligent men I have ever known, and undoubtedly the most ethical, the least compromising, among the most wholly admirable. Important (and enjoyable!) as his musical compositions are; diverting as his occasional writings are (and I suppose some will be gathered for publication in coming months), timeless as Singing Ancient Greek is, for many of us who knew him it is the force and power and nobility and majesty, even, of his personality that will stay with us.

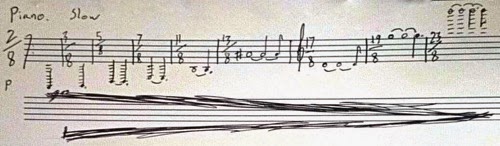

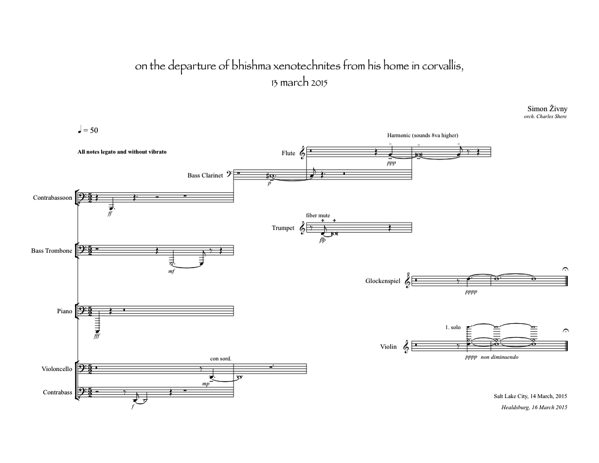

When he moved out of his house into hospice I sent a message to my grandson Simon Zivny, informing him. Simon — bright, young, enthusiastic, and gifted — instantaneously saw the news in musical terms, and sent me back his immediate transcription (listen here):

I immediately heard the piece in orchestral colors, and with Simon's permission I close with the score.

Listen here

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

6 comments:

Such a beautiful tribute to someone you were blessed by knowing. I have a friend going through the same disease now. We live in a world, it seems to me, that believes in explanations, yet more and more of our circumstances defy explanation.

Thank you. I was indeed blessed to know him. And it is by losing such blessings that we come to understand and appreciate them better.

What you say about the belief in explanations, in the face of increasing absence of explanations, is profound; I will think about that for quite a while.

Thank you for your loyal reading, and you occasional response. It means a lot to me.

Wonderful tribute. Thanks for this.

Thank you, Charles. I stayed up tonight to see the beautiful lunar eclipse - these things restore us, I believe.

Fantastic tribute.

Thank you for sharing this.

Doug's name surfaced for the first time in a while. Comparing notes with a new harpsichord client, we discovered a common friend in Doug, with whom he had worked at Pomona. I pulled out the LPs, then scores, and a casette of vocal works Doug had compiled. My first cembalo commission was for Douglas - and the loaner while he waited prompted his reimmersion into keyboard, given its flexible intonation. Douglas Leedy's influence will emerge again later today, when I give a first tuning lesson to a violinist with her first harpsichord.

Post a Comment