Pasadena, December 20, 2016—

MUSIC HAS BEGUN to interest me again – I mean actually listening to it, preferably live — and in the last two or three weeks we've gone to three concerts, all of them involving the piano.

I have a troubled history with the piano. My first lessons were in the basement of the church across the street from my grandparents' house in Berkeley, at the corner of Bancroft and McKinley Streets. This was before the war — world War II, I mean — and I have no recollection at all as to how the lessons went. My grandparents had an upright piano, a wedding gift to them I believe; we certainly never had one in our own home.

Perhaps that's why by the time the war began, when I was six years old, and we moved from the grandparents' neighborhood to the neighboring town Richmond, I was shifted from piano to violin. (Though that must have happened earlier, as I do recall playing violin in a children's orchestra on Treasure Island, during the World's Fair there, which was surely ended by the time the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor.)

When I went away to college, in 1952, I was immediately assigned to a piano teacher, for I'd indicated my preference to major in music. I hated practicing, mostly because I hated scales. The lessons ended after a few months, and I never studied piano again.

That didn't keep me from buying a piano, in 1961 or 1962, when the University of California in Berkeley tore down its practice rooms in order to build a new Student Union. A friend who was a real pianist told me I could get one for $100. He had to have it delivered to his house, and from there he, another friend, and I pushed it the several blocks down Channing Way to our house. I'd rented a piano dolly for the occasion, and somehow we managed the curbs and the steps up to our duplex.

For the next few years I was a self-taught pianist. My only interest in the thing was a composer's interest: checking the physical possibility of fingering, the voicing of chords, the lingering effect of overtones, the sound of staccato, sostenuto, and the like. And, of course, trying to learn to read orchestral scores at the keyboard, which I knew (from my reading) to be both important and routine among composers and conductors.

In those days, too, and for years afterward, I could afford only cheap used turntables, whose problems with flutter and wow were particularly cruel to recordings of piano music — so I rarely bought any. I was an instrumentalist; I'd specialized in bassoon in high school; the orchestral winds and strings spoke much more seductively to me than did the piano which was, it seemed to me, a soloist by its nature, offering no place to hide.

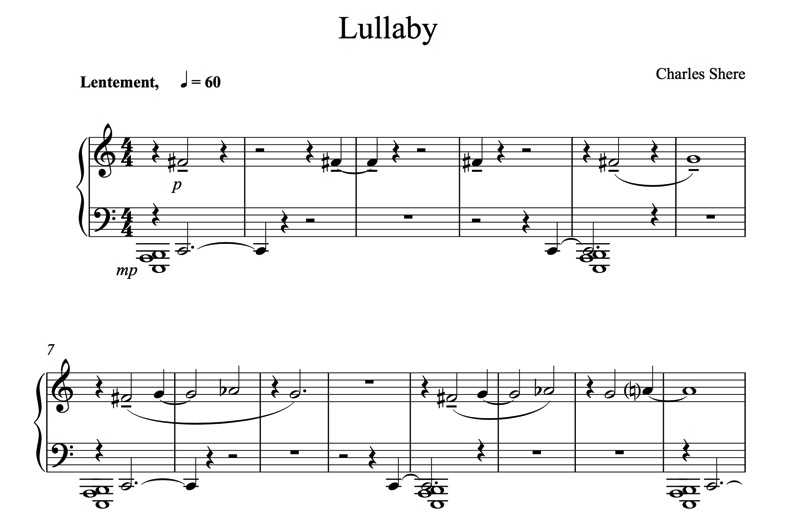

And yet over the years I've composed a few things for piano. My first professional performance was of a piano concerto, in fact; at the Cabrillo Music Festival in 1965, when I was already all of thirty years old. Since then there have been two sonatas and various little pieces, and I've learned over the years not to let my own shortcomings prejudice me against enjoying those of others.

SO IN THE LAST few weeks we've gone to those three concerts. The first was a recital of music by contemporary Italian composers, in San Francisco's Center for New Music. I'd heard about it from Facebook, of all things; one of my Facebook friends is an Italian composer and conductor, Marcello Panni, who I met when he was a visiting prof at Mills College where I used to teach. (He conducted my opera

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, in 1984, and we enjoyed one another's company.)

On November 9 — I hadn't realized it was so long ago! — we went to the Center to hear a piece of Marcello's along with other music by a number of his Roman friends, played by Fausto Bongelli. I was particularly drawn by Marcello, of course, but also by the promise of music by Giacinto Scelsi, a favorite composer of mine. It promised to be an interesting survey.

Bongelli is a very big man. Not stout: big. He looks like he should be smoking a cigar with his right hand, drinking a whisky with his left. Instead he used those hands to assault the piano. He went after it without letup, barely pausing at the end of one piece before attacking the next. There was no way really of knowing what we were hearing when. I listened carefully as a result, forming ideas about the pieces — none of which I'd ever heard before (nor did I know of the other composers on the program) — as much in order to distinguish them from one another as to get to know them for themselves.

Half of my brain is a critic's brain. A critic, I think, leaning on Joseph Kerman's definition, is a person who studies works of art in order to try to find or assess or mostly simply to enjoy their meaning and value. Meaning within their own language and within the history of their art; value not as a rating or an approval (or disapproval) but as a degree of usefulness or beauty or simply interest.

So here I was forced by Fausto's odd approach to the piano recital to work particularly hard as a critic, with the result I think that the other half of my brain, which is shared by a composer and a writer, rarely was able to get involved in the evening. I did think I knew which of the six or seven pieces was Marcello's, and when I spoke for a few minutes to Fausto — so engaging and physically present a man I feel Im on first-name terms! — I turned out to have made the right guess, and had a glance at the score among the disorderly pile of papers from which he'd played this fascinating program.

A MONTH LATER we were back at the CNM, in the heart of San Francisco's Tenderloin District, to hear another piano recital, similar in some respects though quite different in another. We heard a single composition, Dylan Mattingly's two-hours-plus

Achilles Dreams of Ebbets Field, played by another pianist with striking presence.

Kathleen Supové approached the keyboard dressed as Alban Berg's Lulu, in a Louise Brooks hairstyle and a lace-trimmed leopard-print slip. An intrepid page-turner sat at her left, anticipating her sometimes sudden and rather imperious nods and glances. (You can read Patrick Vaz’s evocative description of the evening here.)

Mattingly is young, at the beginning of a career and the end of a serious college education which centered, it seems, on studies in classical antiquity. Achilles Dreams of Ebbets Field has a detailed program fastening its 24 sections, played with only one break serving as a short intermission, to the 24 books composing Homer's Iliad. I did not read the program, and have not yet: I wanted to listen to the music. I was infatuated with James Joyce in my own salad days, and spent a lot of time threading my way through the maze of his Ulysses, and Stuart Gilbert's trot, and all that; I don't particularly want to continue dealing with what I learned, as an English major, to call Secondary Sources.

I have the feeling Achilles Dreams… is in the tradition of Schumann's Davidsbündlertänze, inspired by the composer's acquaintances whether literary or historical or immediate, and as valuable (vide supra) as his expressive responses to these acquaintances can be to another sensibility (namely mine, or for that matter yours). I will say that in spite of the length of the work, and the relative lack of variety of mood, not to mention of tempo and texture, my attention never wandered; I was entranced, you might say, throughout.

This may have been greatly due to the performer. It must be a tremendous undertaking to get to know the details of so large a piece of music and then to find a way to embrace the long trajectory defining its structure. This was only the second time Supové had played the piece publicly, and I had the impression she was still approaching it from its outside, working at various doorways and windows to get into it. Perhaps the piece itself is Ebbets Field: she approached it as fiercely as an Achilles, fortunately without a vulnerable heel. (Unless that of her right hand, which frequently was held remarkably flat, slightly below the fingerboard, even though her fingers were strong and effective in Mattingly's frequently martellato style.)

The sound of the music, to me, lay between Charles Ives (I'm thinking of the Concord Sonata) and John Adams, (say, Phrygian Gates) without ever really being in the least derivative. Perhaps Ives was associated with the ancient Greeks — his New England transcendentalism would make that work — and the Adams style, to put it crudely knitting contrasted with Ives's carpentry, stood for Mattingly's view (or experience) of the contemporary world.

To know, I'd have to hear the piece again, preferably on a recording allowing me to stop and backtrack and so on, and with the score, and with, of course, the program. I am very much interested in the kind of thing Mattingly has attempted here, working with literature and music and history, merging the two halves of the brain, the critic’s and the composer’s.

I confess I went to each of these solo piano recitals with the score of my own second sonata, and shamelessly approached the pianists after their performances to put it into their hands. I hope this will be considered by way of a compliment to them: had I not enjoyed their approach to the instrument and the music, I wouldn’t want them to consider playing my own.

SATURDAY NIGHT we attended a third concert: Eliane Lust, a pianist I’ve known for some years, was playing a concerto with the Kensington Symphony. And it was an engaging program — lightweight, perhaps, but potentially fun: short excerpts from extended orchestral works by Manuel de Falla and Alberto Ginastera; a

Concierto folklórico for piano and strings by John Carmichael; Morton Gould’s

Latin-American Symphonette.

Carmichael, born in Australia in 1930 but now living in the United Kingdom, was the music director (and I suspect therefore rehearsal pianist) of a Spanish dance company, Eduardo Y Navarra, from 1958 to 1963; his Concierto, composed in 1965, reflects this experience, as the titles of its three movements show: La Siesta Interrumpida; La Noche; Fiestas. I found the piece entertaining but shallow, with much repetition and little development. Nor was the solo instrument given much to do. On the other hand Eliane played with her characteristically insouciant elegance, chiselling the rhythmic phrases, voicing the chordal writing imaginatively, cutting through the sometimes gluey string writing with edgy percussive attacks which never, however, seemed contrived as self-display: everything was for the music. I wished she had been playing a Milhaud concerto.

Gould’s “symphonette” — the last of four — was composed in 1941, I think (sources differ on this), and is a better piece than I’d expected. It is certainly light music, as the modest title suggests was intended. The four movements are based on, and titled, Rumba, Tango, Guaracha, and Conga. The writing frequently overwhelmed the community orchestra and its conductor, Geoffrey Gallegos; brass and percussion got out of hand now and then, and the small string sections were often overwhelmed. But there are some nice details in Gould’s scoring: I thought of Mahler now and then.

Marcello Panni, Dylan Mattingly’s parents, and Eliane Lust are all friends of mine — they’ve visited our house and we theirs; we’ve dined together; we all like one another. It can be difficult to write critically about the work of friends and associates, but I’ve always felt the potential gains from communities of interest outweigh the possible harms latent in what’s often called conflicts of interest. Besides, god knows there’s no money involved here…

Motherwell is around the corner to the left from Mark Rothko, whose characteristic red-over-black has the requisite weight and mystery to hold its own among strong company — the Joan Mitchell and Jay DeFeo canvases to its left, and, across the gallery, equally strong work by Philip Guston.

Motherwell is around the corner to the left from Mark Rothko, whose characteristic red-over-black has the requisite weight and mystery to hold its own among strong company — the Joan Mitchell and Jay DeFeo canvases to its left, and, across the gallery, equally strong work by Philip Guston.