Ashland, Oregon, July 26, 2012—

ROMANCE; TRAGEDY; HISTORY; three of the four major categories of the Shakespeare canon, seen within thirty hours, on two of the three stages maintained here by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. And seen in productions of varying degrees of success, in my opinion. The problem, as always in this country — I know nothing of Shakespeare productions elsewhere — is the degree of comfort the producing team has with the presentation of these plays to these audiences. How is Shakespeare relevant, or approachable, or (let's face it) marketable in 21st-century United States of America?Harold Bloom has his own comment on the problem of Making Shakespeare Approachable:

Most commercial stagings of As You Like It vulgarize the play, as though directors fear that audiences cannot be trusted to absorb the agon between the wholesome wit of Rosalind and the rancidity of Touchstone, the bitterness of Jaques. I fear that this is not exactly the cultural moment for Shakespeare's Rosalind, yet I expect that moment to come again and yet again, when our various feminisms have become even maturer and yet more successful. Rosalind, least ideological of all dramatic characters, surpasses every other woman in literature in what we could call "intelligibility."Shakespeare: the Invention of the Human (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998), 209-10The summer of 2012 is not yet the cultural moment Bloom has in mind, not to judge by this year's production of this great Romance; and it was again partly the fault of a single character, Touchstone — here directed to sitcom comedy (like the Romeo Nurse, overwhelming the "rancid" subtleties. All of Shakespeare's romances depend partly on comparisons, contrasts, and collisions of class; but it is what each class representative has to say about the others that is informative and interesting and ultimately useful. In broad attempts to use these contrasts primarily for their entertainment value this informative value is lost.

Too, the language suffers. Too often the actors seem to take little pleasure in the marvelous poetry they are given (even, in Rosalind's case, in prose), as if they're self-conscious about it. Lines are thrown away, or mumbled, or mouthed, or made difficult to register because of absurdities of aural scale caused by the shrill yet bland music in this production, or the alternation of shouts and murmurs. Like Romeo and Juliet, As You Like It contains scores of lines whose beauty brings tears to the eye, even though they're familiar as clichés: today's actors need to trust the poetry, whose familiarity is due after all to its power, not merely the repetition across the centuries which is testament to that power.

The whole first half of this production labors to overcome its unfortunate opening, with a banishment scene made to look absurd rather than cruel. I almost left at intermission. Afterward, though, as would be the case the next afternoon, the production settled in, and Shakespeare shouldered directorial Concept aside. Bloom is right, I think; Rosalind is a magnificent creation. She could converse wittily with Hamlet and Prospero, and the conversation would be rewarding for its substance. Jacques, too — the role set on a woman actor in this production, and why not? — has a mind far subtler and more meaningful than is often thought to be the case (even Bloom seems to neglect her), and is beautifully portrayed here, almost as if to apologize for the overblown Touchstone.

It doesn't help my present mood, on the subject of these productions, that I've just read David Crystal's engaging book Pronouncing Shakespeare (Cambridge University Press, 2005), an account of his work preparing the cast of the London Globe Theatre for a series of performances of Romeo and Juliet in Shakespeare's own language, Early Modern English, at it was most likely pronounced in London at the turn of the Seventeenth Century. The book strikes me as most interesting and useful to anyone concerned about the plays, the author, the productions, and the performances; I'm sure most professionals in the area are familiar with it, and I wouldn't be surprised if it had been read fairly closely by Laird Williamson, who directed the performance we saw yesterday afternoon.

One of Crystal's points, in his short and entertaining book, is that the "authentic" reproduction of the sound of Shakespeare's English does not render the play more remote to today's audience. (I set "authentic" in quotes, but Crystal writes persuasively to explain just how we can know how the language may have sounded.) In today's London, four hundred years later, the linguistic climate turns out to be remarkably similar to that of Shakespeare's day: lots of accents, lots of languages, all present simultaneously, influencing one another at times, revealing differences in ethnic, class, economic, and geographical background.

Williamson's production of Romeo and Juliet transposes the action from early Renaissance Italy to California in the 1840s, when it was in its sad devolution from a Mexican state to annexation by the United States. The Capulets and Montagus are feuding landholding families, the Prince is a U.S. Army general in command of the area. You hear the familiar lines in mostly modern English, with Mexican, Spanish, Afro-American, and east-coast educated accents; often Juliet's father lapses into Spanish when talking to his wife, daughter, or various servants.

The play survives the transposition well; I think it likely does make its relevance to our own time and place more immediately clear to contemporary audiences unfamiliar with Shakespeare. (Not with the story, of course: what tragic love story is better known?) Where West Side Story brings the play to our own context — successfully, I think — this production mediates Shakespeare's setting and our own context through this clever Californification, paralleling the playwright's secondary purpose — his examination of societal mores as they defeat their own intentions — by training the same examination on both our own time and one in the recent past centered on many issues again in the public moment (class, ethnic background, pride, gangs…).

But the playwright's primary purpose is not to instruct, but to entertain, and here this production, like too many productions of Shakespeare, is too often exaggerated, out of scale. No question that the Nurse is often a comic role; but she has serious things to say: in this production the audience is early trained to think of her as little more than a stereotype, and she's rarely taken seriously. Mercutio should be talkative, deft, mercurial; here he's mainly loud.

Fortunately, Mercutio doesn't survive into the second act (there is only one intermission in this production), and after its irresolute opening the production settles into its directorial concept and Alejandra Escalante's portrayal of Juliet becomes more complex and more attentive to the book. In general, it's as if the cast begins to take the text more seriously, as offering real and thoughtful material for them to convey to the audience. And the close, as always, is poignant and affecting.

We come now to Henry V. I do not like this play, as Bloom does not like The Merchant of Venice, so I'll admit to an inability to see or discuss or think about it rationally. I know there's a case to be made for an ironic intent behind it. Henry V is like Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony: its tone must be destroyed in its performance if its real meaning is to be conveyed. You would think, then, that a company used to damaging the tone of Shakespeare's plays would find a brilliant approach to this history: but this summer that doesn't really happen.

The play centers on the young king's successful invasion and seizure of much of France, the result of the pivotal Battle of Agincourt, and in its conclusion on Henry's arranged marriage to the trophy princess Catherine of Valois. There are, God knows, memorable events and moments in the early scenes, but in this production, presented out of doors in the Elizabethan Theater, they were uniformly grey and unappealing, as if the intention were to rob war of any glamor. The frivolity of the French court, a running joke among the British, brought the only moments of light and deftness, and the graceful humor attending Hal's courtship of his dubious "Kate" seemed to offer a civilizing note to what had until then been relentless and glum.

These three plays were undoubtedly chosen with ensemble in mind. England seizing France; the U.S. seizing California. Generational conflicts and commentaries. Spanish, French, Scottish and Welsh accents. Finally, the civilizing effect of romantic love, which resolves conflict by giving in to biological urgency. There is always so much to contemplate here; it hardly matters that irresoluteness and economic realities momentarily blur the perception of Shakespeare's immense and complex landscape.

As always, I deny any attempt here to "review" these productions; there are plenty of reviews on the Internet. Casts and credits are also on line, along with performance schedules:

• As You Like It: Elizabethan Stage, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Ashland, Oregon; closes October 14.

• Romeo and Juliet: Angus Bowmer Theatre; closes November 4,

• Henry V: Elizabethan Stage; closes October 12.

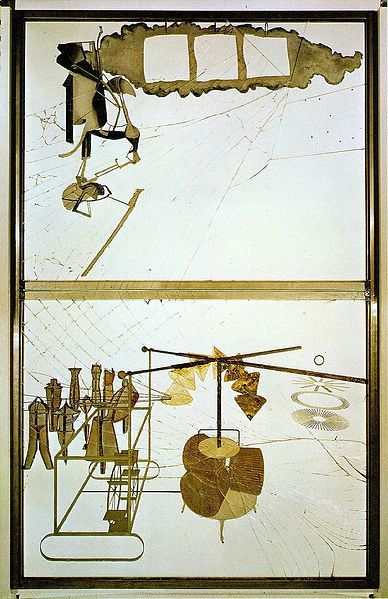

IF YOU'VE VISITED this blog before you're no doubt aware of my long-running infatuation with La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même, the chef-d'oeuvre Marcel Duchamp abandoned in 1923, which has since attained the status of legend within the annals of Modernism. He had worked on it for ten or twelve years; I worked on it longer, ultimately to an even greater degree of futility.

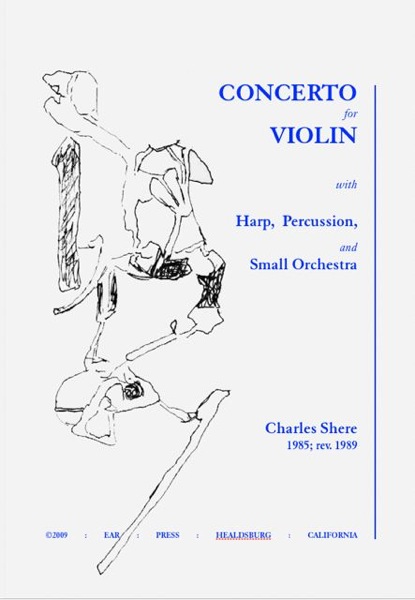

IF YOU'VE VISITED this blog before you're no doubt aware of my long-running infatuation with La Mariée mise à nu par ces célibataires, même, the chef-d'oeuvre Marcel Duchamp abandoned in 1923, which has since attained the status of legend within the annals of Modernism. He had worked on it for ten or twelve years; I worked on it longer, ultimately to an even greater degree of futility. I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED eccentric violin concertos, by which I mean those somehow standing aside from the standard repertory. Mozart's, of course; and the Sinfonia Concertante. Harold in Italy. The neglected ones by Schumann, Dvorák, Goldmark, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Lou Harrison; the familiar but still fascinating ones by Sibelius and Berg. In many of these concerti, it seems to me, the soloist stands somewhat apart from the orchestra, the composer's (and the performer's!) strategy for dealing with the differences between the collaborators in terms of dynamic and tonal range and, especially, potential weight. One doesn't like to attribute too much "meaning" to music, but it's hard to escape the thought that the soloist-orchestra dynamic recalls that between Self and Society, or — better, in my opinion, and certainly more representative of my own attitude — Self and Nature.

I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED eccentric violin concertos, by which I mean those somehow standing aside from the standard repertory. Mozart's, of course; and the Sinfonia Concertante. Harold in Italy. The neglected ones by Schumann, Dvorák, Goldmark, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Lou Harrison; the familiar but still fascinating ones by Sibelius and Berg. In many of these concerti, it seems to me, the soloist stands somewhat apart from the orchestra, the composer's (and the performer's!) strategy for dealing with the differences between the collaborators in terms of dynamic and tonal range and, especially, potential weight. One doesn't like to attribute too much "meaning" to music, but it's hard to escape the thought that the soloist-orchestra dynamic recalls that between Self and Society, or — better, in my opinion, and certainly more representative of my own attitude — Self and Nature.