|

|---|

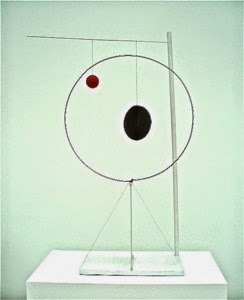

| Installation photograph, Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic, through July 27, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © Calder Foundation, New York, Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, photo © Fredrik Nilsen |

Eastside Road, April 16, 2014—

HOW REFRESHING IT IS, to see an exhibition of an iconic artist, one whose work one knows well enough almost to take for granted, in an installation that restores all his energy, his significance, that reasserts his position within the most magical and optimistic areas of his century.This is what happens in the current show of works by Alexander Calder, beautifully installed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. We devoted only an hour or so to the show: next time we're in town, we'll have to go back. Let the museum itself describe the exhibition:

One of the most important artists of the twentieth century, Alexander Calder revolutionized modern sculpture. Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic, with significant cooperation from the Calder Foundation, explores the artist’s radical translation of French Surrealist vocabulary into American vernacular. His most iconic works, coined mobiles by Marcel Duchamp, are kinetic sculptures in which flat pieces of painted metal connected by wire move delicately in the air, propelled by motors or air currents. His later stabiles are monumental structures, whose arching forms and massive steel planes continue his engagement with dynamism and daring innovation. Although this will be his first museum exhibition in Los Angeles, Calder holds a significant place in LACMA’s history: the museum commissioned Three Quintains (Hello Girls) for its opening in 1965. The installation was designed by architect Frank O. Gehry.Yes, Frank Gehry, the architect. Installing all these works — from table-lamp sized stabiles to enormous mobiles, from small maquettes to huge stabiles — required unusual consideration, and the LACMA website describes The Challenge of Installing Calder in a fascinating and well-illustrated blogpost.

You see three of the earliest pieces in the photo above, with the fascinating Object with Red Ball (1931) at the center. This photo, from a different online source, demonstrates the piece's variability: the red ball and the black "sphere"— in fact two intersecting flat discs — can be positioned at various points along the horizontal rod from which they hang. The piece is a study in spatial relationship, implying motion. I like to look at it, with one eye or both, while walking slowly and smoothly past it, also varying the height of my eyes. No doubt this looks funny to other onlookers: I don't really care.

You see three of the earliest pieces in the photo above, with the fascinating Object with Red Ball (1931) at the center. This photo, from a different online source, demonstrates the piece's variability: the red ball and the black "sphere"— in fact two intersecting flat discs — can be positioned at various points along the horizontal rod from which they hang. The piece is a study in spatial relationship, implying motion. I like to look at it, with one eye or both, while walking slowly and smoothly past it, also varying the height of my eyes. No doubt this looks funny to other onlookers: I don't really care.Object with Red Ball is as significant historically as it is on its own sculptural terms. It was in late 1931 that Calder began homing in on the idea with which he's most generally associated, the gentle movement of various components of his hanging sculptures as they respond to drafts and breezes. His friend Marcel Duchamp gave them the name that's stuck: mobiles. I think we tend to concentrate so much on these kinetic mobiles that we tend to forget their source; the three pieces in the photo above clearly put the Calder of the late 1920s and the first year or two of the next decade in a Surrealist context, particularly associating him with the Catalan painter Joan Miró.

It's easy to think of wit, even whimsy, as the primary effect of these pieces; but it's interesting, I think, to contemplate just what wit (and even whimsy) consists of, just why it should be a significant, even serious component of "abstraction." The beginning, for me, lies in the humor inherent in the sheer physical presence of these objects, made of shapes and substances that are familiar enough, that are combined and integrated in configurations never before seen, that contrast the frailty of their means and substance with the evident permanence of their purpose. These pieces mean to stay. They are here for a reason, however intuitive Calder's method may seem to be. Calder states (via one of a number of intelligent wall-readouts):

The basis of everything for me is the universe. The simplest forms in the universe are the sphere and the circle. I represent them by discs and then I vary them. My whole theory about art is the disparity that exists between form, masses and movement.

|

|---|

| Le Demoiselle, 1939 ©2013 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS) |

Calder's titles are almost always delightful, and delightfully apt. La Demoiselle (I don't know why LACMA's cut-line gives the word a masculine article) is redolent of the crisply feminine fashion-world of 1930s France; it is also both witty and graceful. A mobile hangs from the red stabile base, marrying the kinetic and the stationary — perhaps that's the reason for the hermaphroditic grammar of the title — but acknowledging, through its slender line and its improvised rear leg, the potential flight of even the stationary element.

The mobile had made Calder famous, rightly, and his primary colors, the wit and delicacy of his forms, the immediate pleasure of his work made it accessible. No one ever wondered what his work "meant." And if the man in the street could look at it and say "Why, my kid could do that," well, plenty of primary schools were quick to assign the production of construction-paper-and-coathanger knockoffs to children across the country — in the end only emphasizing Calder's apparently effortless mastery of what is, in fact, a rather tricky exercise in all kinds of balance.

After the war, commissions for large-scale public works began to rush in, and Calder worked away happily and productively into his sixties and seventies. This is the fiftieth anniversary of LACMA's commission of one of his most complex huge pieces, Three Quintains (Hello Girls), the grouping of three stabile-mobiles which for too long was relatively hidden at a corner of one of LACMA's signature ugly-Modernist buildings. I didn't see the piece last week, on our hurried visit to this exhibition; next time I'll be sure to say hello.

One of the most impressive of the big pieces is in fact "only" a maquette for an enormous work placed in Grand Rapids, Michigan: La Grande vitesse, over forty feet high, Calder red, massive, strong, yet lyrical. The maquette, also in plate steel, is only eight and a half feet high, eleven and a quarter feet long; but it crowds and dominates its room, inviting the onlooker to walk around and through it while allowing one to back off and take the whole thing in with one gaze. In the end, though it's forty years removed from Object with Red Ball, it similarly invites contemplation of changing configurations, and, through that, of its place — and the viewer's place — in the universe. Calder's universe, and ours.

|

|---|

| Le Grande vitesse (intermediate maquette), 1969 ©2013 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY |

Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, California; 323 857-6000

Exhibition continues through July 27, 2014

1 comment:

I like the tension created in Calder's sculptures between leverage (fulcrum) and gesture.

The structures are metaphors for the dialectic between animation and gravity--a dance of shapes and gestures.

They're naturally playful, and sometimes they seem attempts at innocence. Inn Kensington had a group of his prints a couple of years ago--magnificent! As good as anything of its kind by Miro.

There's a kind ingenuity in his work which is occasionally suspect, as if he were a garage tinkerer instead of an artist.

Then you see something that just blows you away.

Post a Comment