I WROTE ABOUT the magnificent opera

Einstein on the Beach here a few weeks ago, after seeing the premiere of the present production in Montpellier, on March 16. One doesn’t see

Einstein on the Beach very often; it was too monumental an event to let pass without comment — however difficult it is to describe. The opera was, together with a fiftieth birthday party in Luxembourg, the compelling reason for spending that month in Europe; it was certainly the reason for the mad dash we’d taken across France in the previous four days. When the production’s tour was first announced, in the fall of 2011, we made it a point to plan to see one of the performances in Berkeley, scheduled for October 2012. But the opera is so legendary, was so significant, will be so fascinating and evocative, why not see it more than once? A preview performance of this new production — revival is perhaps the better term — was scheduled in Ann Arbor, and we could probably have gone to it; but wouldn’t it be more fun to see the recréation en première mondiale in France, not so far from Avignon, the site of its original premiere in July 1976? And so we’d bought our airplane tickets, and made our plans.

Since seeing

Einstein in the mid-1980s we’ve seen a number of other Philip Glass operas:

Satyagraha live and live-broadcast from the Metropolitan;

Akhneton in an effective reduced production by an experimental company in Oakland (California),

Orphée effectively staged by Ensemble Parallèle in San Francisco. I even remembered a hallucinatory

The Photographer from a production in Amsterdam, many years ago. They hold the stage beautifully, these pieces, and they’ve grown logically out of

Einstein, but they’ve moved on.

I have an odd fix on Glass’s music: in principle it’s not my cup of tea; I find its repetitive structures formulaic, a postmodern successor to the harmonic sequences of the tonal period of “classical music.” When actually hearing his music, though, I’m frequently persuaded by the melodic contours; the repetitive structures move subtly into larger periods; and I’m reminded of the smooth evolution of music from late Schubert through Bruckner and Sibelius to Glass.

Interestingly, neither Bruckner nor Sibelius composed an opera; and Schubert composed his only early in his short career, with no success. Glass has found a way to bring what had been a nontheatrical kind of music, building its momentum in long abstract periods, into the opera house. It can be argued that Wagner is his predecessor, but I think that’s a mistake: Wagner’s operas are essentially Romantic narrative music-dramas, like those of Beethoven and von Weber, swollen in size: they are not extensive, but bloated. Glass’s achievement has been to separate the narrative and emotional theatrical content of his operas from the musical processes that drive them. His predecessor is not Wagner, whose leitmotives are sonic illustrations accompanying the narrative, but perhaps Bruckner, whose long structural blocks of musical processes construct a sonic architecture within which the listener — and, in Glass’s case, the cast — are able to move, or stop, or listen, or sound, or contemplate.

All that was apparent enough from simply having sat in our box for four and a half hours and watched and listened. Then, though, after the fact, I read the program book, a fine 128-page production with photographs, an introductory essay by the dramaturg Jérémie Szpirglas, the complete text in the original English and French translation, and a characteristically frank, well-spoken, and useful commentary by the composer, as well as a few comments by Wilson:

If I act as an artist, it’s because I wonder why something is.

If one knows exactly what one does, there is no reason to do it.

If I work, it’s to ask myself: What is it?

(The second line is a paraphrase of a

mot of Gertrude Stein’s: If it can be done, why do it? )

And, a page later, referring to Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1977 portrait of Lucinda Childs, who was the choreographer (and partial librettist) of

Einstein on the Beach,

Lucinda est à la fois d’une froideur glaciale et très chaleureuese. On voit dans son regard qu’elle comprend la force de l’immobilité et du mouvement intérieur.

The program booklet was in French, of course; I set the original down from now on in my quotes, and supply my own translation:

Lucinda is at once glacially cold and quite warm. You see in her expression that she has the power of both immobility and interior motion.

Einstein on the Beach is, of course, “about” Albert Einstein, whose pure reason was one of the engines of the modern enlightenment, conceiving ideas so revolutionary — more than any perhaps since those of Galileo — that they are known by the masses. (Or were, in my time: it’s possible that the recent decline in public education in the United States has changed that. I’d rather not think so.)

When Glass and Wilson met, it was inevitable that they would collaborate on an opera. But on what subject? What mythic Twentieth-century subject would provide the subject for the most revolutionary opera since Monteverdi’s Orfeo, which took the mythic inventor of music itself — and let’s not forget that to the ancient Greeks there was no distinction between poetry and music — for its subject? Glass tells us:

Wilson wanted Charlie Chaplin or Adolph Hitler as our inspiration; I preferred Gandhi. Einstein was the choice.

The choice was appropriate for two reasons: narratively, Einstein was of course one of the primary revolutionaries ushering in the modern age. Not only for his insights into mathematics and physics: for his philosophical and moral positions as well. And not only for their fixed and final positions, but for the excruciating positional dilemmas they would precipitate: he was the one who mooted the atomic bomb to President Roosevelt, in order to finesse a victory in the war against the unspeakably evil (and, be it noted, historically retrograde) empires-in-the-making of Hitler and Tojo; but he was also a pacifist:

La pire des institutions grégaire se prénomme l’armée. Je la hais. Si un homme peut éprouver quelque plaisir à defiler en rang aux sons d’une musique, je méprise cet homme… Il ne mérite pas un cerveau humain puisqu’une moelle épinière le satisfait.

[The worst of the herding institutions is called the army. I hate it. If a man can show some pleasure marching to the sounds of music, I don’t trust him… He doesn’t deserve a human brain, since a spinal cord satisfies him.]

Robert Wilson was already predisposed to celebrate Einstein, since his own esthetic had been greatly informed by the mathematician’s discoveries:

Pour moi, une ligne horizontale est l’espace, une ligne verticale, le temps.

C’est cette intersection du temps et de l’espace qui est l’architecture élémentaire de tout.

[For me, a horizontal line represents space, a vertical line, time.

It’s this intersection of time and space which is the elemental architecture of everything.]

And Philip Glass — still quoting from the program booklet — says

Le temps, dans la musique, c’est la durée. C’est l’un des points communs de notre travail : Bob et moi devons travailler en temps réel. Nous partageions une conscience du temps, de la durée. Bob étend le théâtre dans lespace et le temps, je projette la musique dans l’espace et le temps.

[Time, in music, is duration. It’s one of the things in common in our work: Bob and I have to work in real time. We share an awareness of time, of duration. Bob runs theater in space and time; I plan music in space and time.]

EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH unfolds through four acts, each in two scenes, the scenes falling into three groups. Appropriately, it is an opera “about” structure, relationships, and panorama: Einstein is not treated as a character, a biographical subject; he is present throughout as a representative or a symbol of his way of thinking, and of the revolutionary result his thought brought to his century. In fact, the opera is about Einstein’s century, depicted from a very American point of view. The panorama of that century — surveyed from a perspective focussed on the interrelationships of ideas, technology, and humanity — is, I think, what is meant by the “beach.”

The structure, very important in the concept of the opera, is simple: and here I can do no better than translate from the program of the original Avignon 1976 production, as reproduced in the Montpellier booklet:

The opera is constructed not on a literary plot but upon an architectural structure which subdivides the duration of the performance into sections of equal length and organizes them into a succession of three themes each of which is met three times.

On this rigorous scheme Robert Wilson has conceive with great precision a chain of images which are perceived as oneiric visions: visions of landscapes, of a train under way, of public benches… which are grouped around three main visual themes: a Train; a Trial; a Space ship above a field.

On this structure, and simultaneously, Philip Glass has composed music which by its intensity and its repetitive method leads to a hypnotic state. Through its modulatory form, this music attains a profound interiority, finding a place outside of time. And it is precisely the work of Wilson and Glass, each supplementing and reinforcing the other, that both are profoundly concerned with the search for a new manner of perceiving time.

Andy De Groat has conceived choreography on the same principle: sequences based on a very simple vocabulary repeat and trace rigorously drawn forms within the scenic space. [Subsequent to the 1976 production this element has been provided, with equal fidelity to the Wilson-Glass concept, by Lucinda Childs.]

The unity of the opera proceeds from Wilson’s visual constructions, Glass’s music, and [Childs’s] choreography which are organized around a common structure taken as a given:Knee Play 1

| | | |

| Act I

| Scene 1

| A

| a Train |

| | Scene 2

| A

| a Trial (a Bed) |

Knee Play 2

| | | |

| Act II

| Scene 3

| A

| a Space ship above a field |

| | Scene 1

| B

| a Train |

Knee Play 3

| | | |

| Act III

| Scene 2

| B

| a Trial (a Bed) / a Prison |

| | Scene 3

| B

| a Space ship above a field |

Knee Play 4

| | | |

| Act IV

| Scene 1

| C

| a Building (a Train) |

| | Scene 2

| C

| a Bed |

| | Scene 3

| c

| Interior of a Space ship |

Knee Play 5

| | | |

In lieu of intermissions there are five “knee plays,” so named by Wilson because they function as articulations: the audience is free to move about during them. Here is how this schema went in the Montpellier production; italicized words extracted from the libretto, followed by the author’s name in square brackets:

Knee Play 1: two characters, side by side, dressed as Einstein in the famous photograph (short-sleeved white shirt, grey trousers, braces), one reciting numbers, the other singing. It could get the railroad for these workers. It could get for it is were… All these are the days my friends and these are the days my friends… You cash the bank of world traveler from 10 months ago… [Christopher Knowles]

Act I scene 1A Train: an old-fashioned locomotive (19th century) arrives slowly. It could be some one that has been somewhere like them… It could say where by numbers this one has… What is it… These circles… nd that is the answer to your problem… This always be… [Christopher Knowles]

Act I scene 2A Trial 1: a courtroom trial. So this is about the things on the table so this one could be counting up… This one has been being very American… This about the gun gun gun gun gun [Christopher Knowles] … “In this court, all men are equal.” You have heard those words many times before… But what about all women?… “My sisters, we are in bondage, and we need to be liberated. Liberation is our cry… The woman’s day is drawing near, it’s written in the stars…” [Mr. Samuel M. Johnson]

(These “Trials” were alternatively titled “Beds” in the original production)

Knee Play 2

Act II scene 3A Field Dance 1: an abstract, geometrically patterned dance.

Act II scene 1B Night Train: a couple vignetted on the platform of an observation car, crescent moon above

Knee Play 3

Act III scene 2B Trial/Prison: The song I just heard is turning… This thing This will be the time that you come… This will be counting that you always wanted has been very very tempting… [Knowles]

I was in the prematurely air-conditioned supermarket

and there were all these aisles

and there were all these bathing caps that you could buy…

I wasn’t tempted to buy one… [Lucinda Childs]

I feel the earth move… I feel the tumbling down tumbling down…This will be doing the facts of David Cassidy of were in this case of feelings… [Knowles]

Act III scene 3B Field Dance 2

Knee Play 4

Act IV, like Act II, lacks text in the program as distributed; the small chorus and occasionally vocal soloists simply count: one two three four five six seven eight…

Act IV scene 1C Building: here, an extended improvised tenor saxophone solo by Andrew Sterman

Act IV scene 2C Bed: extended vocal solo (Hai-Ting Chinn)

Act IV scene 3C Spaceship interior: a complex simultaneity of actors, dancers, and scenic elements

Knee Play 5 The day with its cares and perplexities is ended and the night is now upon us… Two lovers sat on a park bench… “My love for you …has no limits, no bounds. Everything must have an ending except my love for you…" [Johnson]

In the concluding Knee Play the locomotive so prominent in the first scene has been replaced by a bus, as Einstein’s discovery of the principle of relativity, conventionally explained by the analogy of the different perceptions of a single event by a person standing on the ground and another on a moving train, has been replaced by everyday experiences felt by ordinary people everywhere.

So the curve of the opera, if you will, is from the interior mental process of Einstein, contemplating the cosmos as it is and formulating a relational theory that explains it, to the interior emotional response to a similar contemplation as it is announced and expressed, in mundane language, by an ordinary person.

And (to continue this compromised, reductive view of the opera) the peak of that curve is the depiction of the intricacies involved in such contemplation, and the consequences the awareness and expression of such intricacies entail, in public and societal settings.

Einstein on the Beach is postmodern opera at its inception. It’s nothing if not recursive, self-referential, intertextual, rhetorical. But through the striking clarity of Wilson’s vison, the hypnotic effect of Glass’s score, the mesmerizing clarity of Childs’s choreography, and the easily apprehended and disarmingly simple texts, its performance is overwhelming and unforgettable. One looks back on attending it with awe and pleasure, finding detail after detail further enriching the artless grandeur of its concept, further clarifying its relevance to ordinary life in this twenty-first century.

In my own experience, facing works of art throughout my life, it ranks with visiting the Greek temples at Paestum, seeing Vermeer’s

The Milkmaid, reading

Finnegans Wake, hearing

Goldberg Variations. I thank Wilson, Glass, and Childs for the privilege of sharing their insight. In this opera they have achieved — through considerable work and private sacrifice! — a timeless work of art. The least anyone can do, given the opportunity, is to see it, and celebrate it.

There's so much to see on a walk like this; so much to wonder about. What's that wildflower, for example, that sports both yellow and orange blossoms on a single plant? The leaves suggest some kind of pea, but what is it?

There's so much to see on a walk like this; so much to wonder about. What's that wildflower, for example, that sports both yellow and orange blossoms on a single plant? The leaves suggest some kind of pea, but what is it?

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this?

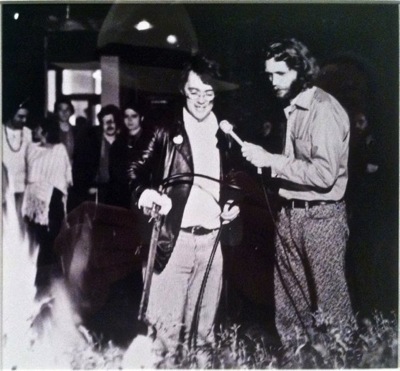

And then Lindsey, who'd been inspecting all this somewhat more attentively than I had, called out: Charles! Did you see this? Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.

Oops. I just fell into my own trap, didn't I? Anyhow, there's the late Terry Fox, I think perhaps as principled and pointed a Conceptualist as any of them, who intuitively understood the degrees of irony attendant on his work, his kind of art; he's gleefully concentrating on the destructive beauty and the physical enjoyment of directing his torch against that foliage; there's the Charles Shere of forty-two years ago, equally rapt at the flames and their work and meaning.